Book #49 was Tom Tomorrow’s Hell in a Handbasket. This was an entertaining volume of Tomorrow’s This Modern World strip, particularly since these strips were written and illustrated during the Dubya Administration. Of course, with Tomorrow, you’re not really going to laugh at this if you’re not a lefty. Even so, Tomorrow’s trusty four-panel setup, with snarky text often spilling across the top end of the squares and its adept use of repeating imagery from panel to panel, has been a dependable strip for years. Tomorrow’s strip serves as an antidote to the comatose offerings of Marmaduke and The Family Circus. (Podcast interview.)

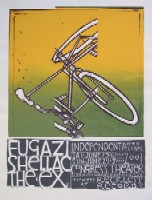

Book #50 was Jay Ryan’s 100 Posters, 134 Squirrels. I was turned onto Jay Ryan by Mr. Pete Anderson, who insisted that I interview the man when he came into town. Since Pete is a guy who can (mostly) be trusted, I fulfilled my pledge, having only a foggy notion of Ryan’s work. What I didn’t realize was that I had actually known Ryan’s work without realizing it. Over the last ten years, Ryan has used a silkscreen process to create garish posters, mainly for indie and emo bands, that are quite distinct with their splashy yellows, reds and greens. They often feature animals and contain little stories of their own (consider the Shellac poster contained on this page, featuring astronauts fighting off a legion of squirrels). This Punk Planet volume collects 100 of Ryan’s posters. The “137 Squirrels” of the title refers to little squirrels that Ryan is fond of including within his work, often sneaking them into secret places within his tapestries. There are some 137 of them within this book. (Podcast interview.)

Book #50 was Jay Ryan’s 100 Posters, 134 Squirrels. I was turned onto Jay Ryan by Mr. Pete Anderson, who insisted that I interview the man when he came into town. Since Pete is a guy who can (mostly) be trusted, I fulfilled my pledge, having only a foggy notion of Ryan’s work. What I didn’t realize was that I had actually known Ryan’s work without realizing it. Over the last ten years, Ryan has used a silkscreen process to create garish posters, mainly for indie and emo bands, that are quite distinct with their splashy yellows, reds and greens. They often feature animals and contain little stories of their own (consider the Shellac poster contained on this page, featuring astronauts fighting off a legion of squirrels). This Punk Planet volume collects 100 of Ryan’s posters. The “137 Squirrels” of the title refers to little squirrels that Ryan is fond of including within his work, often sneaking them into secret places within his tapestries. There are some 137 of them within this book. (Podcast interview.)

Book #51 was Harvey Pekar’s Our Cancer Year. Yes, I realize there’s a lot of Pekar on this list. But if I was going to talk with the man himself, I wanted to be expertly prepared. As it so happens, I hadn’t read Pekar’s Harvey Award-winning graphic novel and was touched by Pekar’s honesty in describing his testicular cancer, the hospital treatment that pulverized his physical form, and the despondent person he turned into as he wondered whether he would continue to live. Our Cancer Year was a major turning point for Pekar as an author (and I should note that this was cowritten by his wife, Joyce Brabner), demonstrating that Pekar’s concentration on the quotidian was even more poignant when juxtaposed against a mortal illness. For those who feel that the American Splendor movie sufficiently captured Pekar’s battle with cancer, I urge you to go directly to this volume and get the real story. (Podcast with Pekar and Haspiel.)

Book #52 was Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor: The Life and Times of Harvey Pekar. If you’re looking for an entry volume on Pekar, Life and Times is your bet. It collects many of the stories that later found their way into the 2003 film of the same name (specifically, two previously issued and now out-of-print Splendor bound volumes). Plus, you get the PB&J-like comic combo of R. Crumb drawing Pekar, among other talented artists such as Sue Cavey and Gary Dumm. What makes the American Splendor stories so mesmerizing, in fact, is Pekar’s great ability to match up the right artist with the right story, causing some of the narrative tropes to take on a new context. (For example, Harvey’s co-worker, Mr. Boats, is depicted entirely differently by each artist.) This is an essential volume for anyone who gives a damn about personal comics. (Podcast with Pekar and Haspiel.)

Book #53 was Harvey Pekar’s The New American Splendor Anthology. A continuation of the previous Pekar volume, this book contains several entertaining stories, such as Pekar depicting his zeal for record collecting and Toby’s infamous Revenge of the Nerds partisanship. It also contains art by Chester Brown. While not as consistent as the main volume, in large part because poor Pekar is resolutely determined to get everything of his in print so he can make a few bucks, this volume still lives up the promise of the cover, offering truth “from off the streets of Cleveland.” (Podcast with Pekar and Haspiel.)

Book #54 was Gina Frangello’s My Sister’s Continent. I had mixed feelings about this book. I like Frangello’s voice, her fondness for playing with taboos, and the novel’s wry commentary on Freudian precepts. I found the father to be an almost Moliere-like figure, satirically saddled with AIDS and many other problems. But I didn’t buy the twin sisters’ character transitions and I felt the book’s resolution was forced. Still, Frangello is definitely an author to watch. She has a delightfully insouciant attitude about deviance. (Podcast interview.)

Book #55 was Sarah Waters’ The Night Watch. Contrary to other reports, this isn’t a total departure from Waters’ other romps, but this fascinating novel is an inevitable evolution — the absolutely right step for Waters to take as an author. I’ve come to the conclusion that, for a literary author, the fourth or fifth novel is often the make-or-break point for stylistic evolution. Consider David Mitchell’s successful transcendence from baroque plots into the deceptively simple Black Swan Green. Or Martin Amis’s Money. Or Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn. Or Richard Powers’ defiant swing into dystopia with Operation Wandering Soul, followed by the metafictional Galatea 2.2. These were all moves that nobody could see coming. And I would argue that The Night Watch can also be added to the long list of transition novels which demonstrate that an author is more than we expect her to be.

Book #55 was Sarah Waters’ The Night Watch. Contrary to other reports, this isn’t a total departure from Waters’ other romps, but this fascinating novel is an inevitable evolution — the absolutely right step for Waters to take as an author. I’ve come to the conclusion that, for a literary author, the fourth or fifth novel is often the make-or-break point for stylistic evolution. Consider David Mitchell’s successful transcendence from baroque plots into the deceptively simple Black Swan Green. Or Martin Amis’s Money. Or Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn. Or Richard Powers’ defiant swing into dystopia with Operation Wandering Soul, followed by the metafictional Galatea 2.2. These were all moves that nobody could see coming. And I would argue that The Night Watch can also be added to the long list of transition novels which demonstrate that an author is more than we expect her to be.

Waters shifts to a completely different timeframe (in this case, World War II and just a few years after) and a very intriguing structure, splitting the book into three sections, the events unfolding in reverse order (1947, 1944, 1941). It’s interesting to see Waters paint herself into a corner like this, particularly since this book comes after the can’t-put-down Fingersmith. Waters has always been a meticulous plotter, but this reverse structure forces her to get inside the heads of her characters. But the structure also restricts her, because she can’t lay all of her cards on the table. Secrets must be kept silent, only to be revealed later. And this liability both mars the book (or at least it made me a bit antsy), yet allows Waters to demonstrate that she can be a very adept psychologist. The book’s structure causes her to focus on how these characters shift over the years and are influenced by each other, particularly when their desires are so closeted.

It helps that she gets wartime London so very, very right and that the novel contains Greene-like imagery (many colons linking sentences, as well as such cinematic description as a bright light illuminating the very threads of clothing). For fans of the romp, there are still plenty of juicy moments (and, in particular, many thighs). (Podcast interview.)

© 2006, Edward Champion. All rights reserved.

You’re much too kind, Ed. In reality, I can (barely) be trusted.