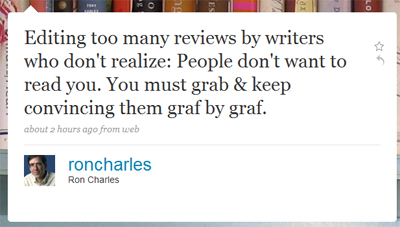

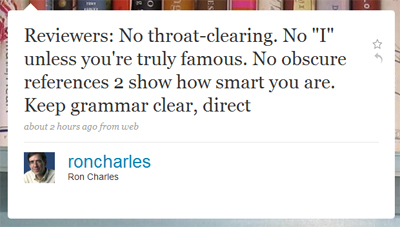

On the morning of July 21, 2009, Washington Post books editor Ron Charles expressed some concerns about book reviewers on Twitter:

At the risk of clearing my own throat (and with all due respect to Mr. Charles), I’m wondering if the 2008 winner of the Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing really has a handle on the type of writing that is likely to attract readers to his newspaper section.

Mr. Charles’s editorial sensibilities call for clear and direct writing. But his other entreaties are problematic. He asks that a first-person perspective or a sense of playfulness through reference — vital variables that might permit readers to get excited, interested, or enthused about a book — be omitted from the equation. Mr. Charles cannot seem to corral the idea of grabbing an audience with each graf with the possibility that readers may be interested with what a particular voice has to say (see, for example, the rise of litblogs over the past six years). Indeed, if Mr. Charles is desirous of a more objective journalistic approach, should not the ideal reviewer be someone who permits a reader to make up her own mind? Mr. Charles’s sentiments appear to reflect a newspaper culture in which personality or perspective — those indelible human traits that make us interested in people on so many levels — don’t get a hot seat at the formal table. Unless, of course, the reviewer is “truly famous,” which connotes a troubling elitism that runs counter to Mr. Charles’s seemingly egalitarian-minded agenda.

We should probably ask ourselves whether there is even a “general audience” for books. I think a case can certainly be made, provided you keep in mind that a “general audience” doesn’t just consume the type of pretentious literary fiction involving suburban asshats and cricket bats. We have seen millions of people get excited over the Harry Potter books (and their cinematic counterparts; see the box office bonanza in the past week). As I discussed with Sarah Wendell and Candy Tan in a recent podcast interview about the romance genre, over 64 million people claimed to read a romance novel in 2004. If Mr. Charles is genuinely committed to a “general audience,” surely he would open up his books section to more romance coverage. (Certainly, Mr. Charles’s coverage of Nora Roberts is a start.) And if the Washington Post is sincerely devoted to attracting a “general audience,” they may wish to do away with the annoying and obtrusive registration prompts that pester us for personal information.

But let’s examine a typical lede for a Washington Post review. Let’s take, simply at random, the first fiction review on today’s Washington Post books page: Mke Reed on Colum McCann’s Let the Great World Spin. Here’s the lede:

As the narrator of Colum McCann’s new novel sees it, Philippe Petit’s tightrope walk between the World Trade Center towers in 1974 triggered a quietude generally unknown to New Yorkers.

We can do away with the superfluous opening clause. There’s no need to inform the reader that this is a review about Colum McCann’s latest book. We already know this. So this leaves us with:

Philippe Petit’s tightrope walk between the World Trade Center towers in 1974 triggered a quietude generally unknown to New Yorkers.

Okay, we have a few interesting concepts to play with here. There’s the exciting prospect of Philippe Petit’s tightrope walk, which is rendered remarkably cold and objective through the bland reportorial phrasing. There’s the more intriguing concept of “triggered a quietude generally unknown.” That phrasing is clumsy, hardly as “clear” and “direct” as Mr. Charles demands. (Is the “triggering” a reference to 9/11? Were New Yorkers really quietly in awe for the first time in 1974?) But there’s some poetic potential here. Perhaps if we take the metaphor and front-load it at the beginning of the sentence, we might have a more compelling lede:

His high wire walk between the twin towers triggered an explosive awe among New Yorkers.

Okay, this isn’t perfect, but it’s an improvement. If the reader is unfamiliar with Petit (or familiar with the 2008 Petit documentary Man on Wire), she’ll be compelled to move onto the next sentence. By switching “tightrope” to “high wire,” we not only provide cultural context for a reader (“Hey, isn’t that the Man on Wire documentary?”) who soaks up art more from cinema than from books, but we also neatly foreshadow the “explosive trigger” metaphor later in the sentence. (Do you cut the red wire or the green wire?) By removing the subjective “generally unknown” assumption about New Yorkers, we do away with a superfluous aside that has little to do with the paragraph’s main purpose here.

With a few modest editorial changes, not only do we have a lede that is more of interest to a general audience, but we also don’t insult the audience’s intelligence by littering their attentive bin with the detritus of clinical phrasing.

Of course, one can avoid these disastrous results by daring to write in the first-person. Ernest Hemingway once wrote an essay about writing in the first-person — which can be found in A Moveable Feast — in which he suggested, “When you first start writing stories in the first person, if the stories are made so real that people believe them, the people reading them nearly always think the stories really happened to you.” Hemingway was referring primarily to fiction, but the advice nevertheless points to one primary deficiency among the newspapers — namely, an ability to give the reader a sense that he is a colleague, not some peon to be dictated to, and that literature is something to be experienced rather than cheerlessly discussed over tea and scones.

[…] golden-voiced Ed Champion takes exception, and throws down the literary reviewing gauntlet. Mr. Charles’s editorial sensibilities call for clear and direct writing. But his other […]

Aren’t there plenty of places to publish and/or share the kind of review you are promoting, though? I see no problem with Ron Charles setting these guidelines for his particular publication –

Matt: Well, if you like cold snag-laden ledes like the one I referenced and cleaned up above, that’s your business. The problem is that these lifeless and/or generalized sentences have also polluted the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times.

From today’s Michiko review: “A year ago it would have been hard to imagine a book about the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department making it onto people’s must-read summer reading lists.”

From Robert Crais’s review of Westlake: “Before Janet Evanovich brought us Stephanie Plum, Don Westlake was the Grand Master of Criminal Laughs with his hilarious novels about professional thief John Dortmunder.”

Honestly, readers are not infants. They were interested in economics before the recession (or does nobody remember last summer’s difficulties?). They know who Janet Evanovich is (and is she really doing what Westlake did with Dortmunder)?

All I’m asking here is for newspapers not to treat their general audiences like nitwits. It doesn’t help that these dull and condescending ledes are seemingly written by people who haven’t laughed since the Carter Administration.

I’m not saying I like them or don’t like them; I’m just saying, there’s an audience that appreciates that style. Book review outlets need to be creative, but careful with the creativity – as with the piece I wrote about on libraries stretching their mission to include computer technologies, they need to consider more than the present moment and the bottom line.

The Crais review lede isn’t the strongest, but he is trying to set the context for humor-laden mysteries and the stark (ha) fact that aside from Evanovich, crime fiction and funny haven’t gone hand in hand for a very long time. Maybe Carl Hiaasen would have been a better comparison, but he doesn’t write series, and what few comic crime novelists remain generally do not write series, or if they do, they don’t sell nearly as well as Evanovich.

Also, a stronger case for what Ed’s arguing against is Maureen Corrigan’s review of Nora Roberts’ BLACK HILLS. The opening paragraph practically spits out a loogie *and* dashes headlong into constant use of “I”:

“It doesn’t much matter what I say about this new Nora Roberts novel; most of the adult female population of the planet is going to read it anyway. It’s a staggering understatement to say that Roberts is review-proof. There are more than 300 million copies of her books in print, and she’s written 160 bestsellers, 39 of which have debuted at No. 1. So let’s step away from Roberts and her books for a moment and, instead, consider me.”

Then come paragraphs two and three, which is all abouut Maureen, little about the book:

I’m the fall guy here — the stooge who’s been assigned to review “Black Hills” — and whatever I say about Roberts is going to affect me a heck of a lot more than it’s going to affect her. If I pan the novel, I come off as a snooty-pants literature professor, and I’ll be deluged by e-mails from her ticked-off fans. If I gush over it, I’ll be suspected of trying too hard to be just a regular gal, a self-conscious populist, like Sen. John Kerry on the campaign trail back in 2004, ordering a better class of cheese on his Philly cheese steak.

So here I am, caught between a rock and a hard place. Roberts’s feisty heroines are often stuck in this kind of fix at the climax of her tales just before a deus ex machina in the form of Mother Nature or a hunky guy drops in to rescue them. That’s why women read Nora Roberts: to live out vicariously the fantasies that real life doesn’t provide. Well, I’m going to live out a personal fantasy for a moment and pretend that it’s still the Golden Age of Critics: Mencken, Parker, Woollcott, Wilson — witty gatekeepers of culture who said what they thought without fear of the backlash of the booboisie or the demagogy of the Internet.

Finally, finally in paragraph four, do we come to what ought to be the lede: “I’m going to say what I think straight out: “Black Hills” is synthetic mind candy.” And the rest of the review more or less backs it up (although the “booboisie” line was over the top), but did we really need those first three paragraphs? No.

And yet I am torn, because Corrigan clearly was entertaining herself here, which I wholeheartedly endorse. But maybe she’ll have a gander at Ron’s generally sound tweets and change her ways in the future?

Hm. I disagree with your edit– I think it’s necessary to mark off the thought about Philippe Petit as belonging to the narrator and not to McCann or the reviewer (or Philippe Petit for that matter). It’s a question of keeping things clear and attributed.

You know what really bugs me about that Nora Roberts review? That it is unnecessary. She’s right – no one needs to review a Nora Roberts book because her readers are very faithful and it will sell regardless of the review (in fact I doubt many of them will even read a review). It’s just unnecessary. That doesn’t mean anything negative about Roberts – you could say the same thing about the last Harry Potter book or Tom Clancy or Stephen King or Grisham, etc. They don’t need to be reviewed.

So here’s a crazy thought – how about using that precious review space to write about a book that doesn’t have a built in audience and thus introduce a new author to your readers? Wow – can you imagine that?

[…] This post was Twitted by EliseBlackwell […]