I used to write in longhand all the time, filling up five-subject notebooks with the predictable angst of a young man in his early twenties and several early starts on stories, plays, and screenplays that I would revise or abandon. Taking notes was once the thing to do. Back in the nineties, when I wrote film reviews, half the critics took notes. And I learned to write in the dark by taking up large sections of the paper, noting a sentence and then sliding my pen downward to another sector. I felt that it was important to be true and accurate to any crazed thoughts or feelings, even the half-assed ones that I could dredge up in a pinch. Today, thanks to reduced column inches (and reduced journalistic expectations), very few critics, aside from those still writing reviews longer than 600 words, take copious notes anymore, whereas I still obstinately scribble without looking down at the pen. I suppose it’s the writer’s equivalent of learning how to assemble a weapon while blindfolded.

The result of all this scribbling has involved quite a few notebooks, most of which I have kept in two file drawers. I’ve just pulled one out at random and I see a drawing of a floor plan for a San Francisco streetcar. Flipping the pages, I see lists of interesting words I’ve noted in novels, such as “contrapposto” and “ephemeron.” There’s an awkward poem that begins with the line “Pigeon pecking pieces from discarded pizza boxes / Whopper wrappers flayed upon a health nut in detox.” I see a hasty budget I’ve drafted for a film shoot, noting the costs of renting fresnels, Tota kits, flex-fills, and C stands. Another page offers this curious list:

The result of all this scribbling has involved quite a few notebooks, most of which I have kept in two file drawers. I’ve just pulled one out at random and I see a drawing of a floor plan for a San Francisco streetcar. Flipping the pages, I see lists of interesting words I’ve noted in novels, such as “contrapposto” and “ephemeron.” There’s an awkward poem that begins with the line “Pigeon pecking pieces from discarded pizza boxes / Whopper wrappers flayed upon a health nut in detox.” I see a hasty budget I’ve drafted for a film shoot, noting the costs of renting fresnels, Tota kits, flex-fills, and C stands. Another page offers this curious list:

- Party Animal

- Collector

- Amateur Sleuth (Sam)

- Femme Fatale

And I instantly recall the moment in Java Beach when I wrote this all down, along with the research I did for a short film I wrote, but never saw through to production, called “The Collector.” Then there is this section from an entry titled “Observations in the Mission”:

At Muddy Waters, two ladies talk. One is more short-haired than the other and is enamored with such words as “never,” “layoff,” and “responsibility.” She keeps her left hand locked on the table, perpendicular to the surface. Her thumb sticks up. There is almost a butterfly-like spread, ever so slight. Perhaps the modest gust from the door can be felt this way. Her companion listens. “You are a robot,” says the angry friend.

These are curious details to observe. And I chide my younger self for not being more careful to observe the specific hairstyles of the time, which would perhaps be of greater value to me in reconstructing the moment. I am also needlessly zealous about the hand gestures. But I do remember being particularly interested in body language. Still am.

But sometime around the year 2000, I cut down on notebooks. I figured that anything that I could observe would be permanently captured on my hard drive. But I’ve had a number of hard drives die on me and I haven’t always been able to revive the files. A friend of mine just lost her thesis this way. We get so caught up in the act of writing that we forget that our tools are sometimes more fickle. And even if we do manage to backup our data, there’s always the possibility that it might be accidentally deleted or lost within a baroque directory structure.

Not so with notebooks. Like analog books, one flips through any notebook and finds a diagram or an abandoned idea. This is rather similar to the unexpected book you find in a library or a bookstore that just happens to be situated close to where you’re standing. Many of the discoveries are useless, but some are surprising. Some fresh idea you think you possess now was actually in some primitive gestation a decade ago. Even some phrases are similar. Your voice is yours, even when you didn’t quite know how to express it in early days. Ten years from now, will we be able to do the same with our blog posts and tweets?

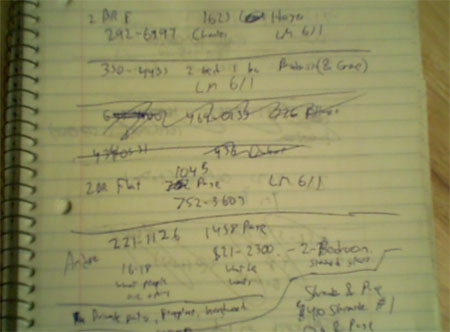

That picture above is from an apartment hunt. I can adduce from the squiggles the apartments that didn’t pan out. And I can track the specific order in which I located an apartment by looking at this page vertically. I have the price ranges of apartments in San Francisco at a specific time. I also see that with this particular quest, I had my eye on the Haight Ashbury neighborhood (which I didn’t end up moving to, but eventually did later).

Since I’ve been less prolific with notebooks in the past nine years, I wonder how many ideas or thoughts or unintentional chronicles (such as the above) that I’ve lost. Smartphones may permit us to text our friends or send an email on the fly, but don’t we have some obligation to preserve our online thoughts? We call an Apple laptop a “notebook,” but is it really a proper notebook’s equal? Our pens do not have delete keys. We cannot take back a written thought, except by scratching it out or burning it. I wrote about linkrot and the problems with online permanence back in August. And it occurs to me that we may be driven to confess our most private details to Facebook — little thinking of the manner in which the social network giant is profiting — because we perceive it to be the new notebook.

But looking through even this one notebook, I can’t imagine a more foolproof technology. And I’m wondering if I should use notebooks more. Computers have produced interesting blogs, wondrous photos on Flickr, and a culture that is more documented than ever before (at least so long as the technology holds). But what about the subconscious buried within us? If we are prohibited from expressing unpopular or strange ideas on social networks because of what others might say or think, then is Twitter so reliable a tool? Could Kafka have written “The Metamorphosis” if commenters were constantly heckling him about his silly bug story? (Conversely, if Kafka couldn’t count on Max Brod to burn his papers, would he have succeeded in closing his online accounts? Or would the cache images live on forever?) If you’re at a party tweeting the names of people arriving into your BlackBerry, are you really being social?

I’m not against technology or e-books. The Internet has given us many great things. But I do feel it’s important to always contemplate the purpose and usage of any new development. If 90% of the reading public prefers analog books over digital, then now is not the time to declare a revolution or to suggest that the days of printed books are over. Moving forward and adopting tools is great, but maybe there’s more life in the dead tree technologies than some of us are willing to admit. Hell, maybe there’s even a good deal on an apartment vacant for years.

© 2009, Edward Champion. All rights reserved.

Great observations about notebooks, especially the way they can be such visceral prompts: the muscle memory bubbles up when we see a page and remember exactly where and when we made those scribbles.

I do most of my writing long-hand in spiral-bound sketch books (I like the unlined pages and thick paper), and my notebooks are a mishmash of stories, notes, and work: use-case diagrams and pseudocode bumping against prose. I like the immediacy and temporality of these notebooks.

The one thing that makes relying on notebooks difficult, though, is that they’re hard to organize. From the outside, they all look a lot alike, and though I try to scribble an index on the cover of each, that gets muddled up with phone numbers, tracking codes, and deadline dates. When I try to find something in an older notebook, I often get caught up in the things I’m not looking for, like an old operating system trying to read a badly fragmented drive. But I think that’s a fair trade for the notebook’s physicality, flexibility, resilience, and resistance to data rot.

LOVE this post. As much as I use my digital notebook tools, I still lean toward a plain old notebook for pure brainstorming. The main problem: I find it very difficult to throw OUT these scribble-filled notebooks. Add that to my natural packrat tendencies and…well…we need a bigger house.

I still write longhand, too. And if I’m interviewing someone for an article, I always write things down in one of those spiral-bound steno notebooks, even as I record them with my fancy little digital recorder (which I finally got around to buying—have not yet dropped it in a puddle). Over time, I’ve figured out that I almost never refer back to the recording and almost always just use my notes.

I’m sure this says more about me (and perhaps my age—34) than it does something essential about any medium. But when I have a pen in my hand and I’m scribbling on paper, I’m more on: I’m listening harder, the brain is working a little faster to analyze or edit whatever it is I’m doing. I even write a little more cleanly. Which results in a better product, even if I can barely read my handwriting later.

I never look at old notebooks for fiction writing. I think this is mostly to avoid nausea. But I love looking at the notes I took when I was interviewing people (I tend to keep the same notebooks for quite a while, since I don’t do a lot of journalism)—when I look at the scrawled words on the paper, I’m right back there, even if the interview happened years ago.

“If we are prohibited from expressing unpopular or strange ideas on social networks because of what others might say or think, then is Twitter so reliable a tool?’

When I think of Facebook or Twitter, I think of social control. Nothing private gets expressed on social networks, except by attention seekers. It’s one great effort at self-presentation, and self-presentation is, by its very nature, not private, and is generally superficial. The notebooks have the advantage of being designed NOT to see the light of day, and in that sense they are more honest, less contrived, and, dare I say, more real.

Having said that, there is no reason that every stray thought which is captured on a laptop needs to be published to Twitter or Facebook, but the ease with which it is possible to pass on the minutiae of daily life to “friends” makes it almost inevitable. At the same time, the presence of social networks tends to dictate the general tenor of discourse available to our imagined audience, which means a sort of preemptive self censorship is at work, which dictates purpose, audience, form and even content. Notebooks don’t do that to us.

Among the people I know on Facebook, most posts are entirely innocuous — those who have kids post about their kids a lot (i.e., too much), others share their travels, daily work annoyances (never using names of colleagues, of course), their new enthusiasms among movies, TV, music, books, etc., and above all, everyone — commenters even more than the original poster — tries to be funny. The “funny” part especially gets tiring. Facebook’s not the place to share anything truly important to the core of an individual. Blogs seem better for that.

People who prefer ink, paper, and regular books may ALWAYS make up 90% of the population. Surely most people would prefer to read an illuminated Bible written in a beautiful, flowing hand: printed on vellum, bound in leather. The trick is trying to make the cheap new medium beautiful. To let the paupers also smell roses.

NOTE: not that anyone who can afford a Kindle or Nook or any of that shit are paupers. Stealing good old paper books off Strand carts is still the cheapest way to get the best “deal” on books in NYC.

Ms. Jones said: “The trick is trying to make the cheap new medium beautiful.”

Agree completely. And I think we’re pretty close. I suspect that some form of the classic rules of book layout (have you read The Elements of Typographic Style, by Robert Bringhurst? I’m always recommending that book to everyone; it’s awesome) will apply to electronic readers, just as they have turned out to apply to web pages. Remember when the Internet used to be, typographically speaking, really ugly? Now it’s only kind of ugly, and getting less ugly every year. Electronic readers can’t be too far behind.

Dear Mr. Jones,

It has been called to my attention that you are in fact of the male persuasion. Please accept my sheepish apology.

Tip of the tophat to you; now we don’t have to duel or whatever.

I enjoyed this post and I wholeheartedly agree with you on the usefulness of notebooks. Keep in mind though, notebooks can be lost as well.

One piece of my own writing that I have lost and would do a lot to get back was written in a notebook. In August before my freshman year at college I participated in a school sponsored wildlife trek in Killarney Park, Ontario for three weeks. At the end we each had to spend 36 hours alone on the edge of a pond, out of sight of anyone else, without food. I didn’t stray more than 10 feet from my sleeping bag and spent my time writing (we weren’t allowed to read) – it was a writing experience unlike any other I’ve had since. I mostly chronicled the spring and summer before I went off to college and did so with a level of energy and conviction that I never brought to any of my college papers. I put the notebook in a cabinet drawer and sometime after moving out of the dorm and into a new school I lost it. Had I written in a laptop computer instead of a notebook would I still have what I wrote? Probably not. All writing is impermanent in some way. I just wish I could look through it the way you can look through yours.

The comfort level with the traditional notebooks are unmatched. I can not ever think of writing a piece of poetry on my Lappy.Certain things are never done w/o pen and a notebook 😉

Keep penning!

Biao