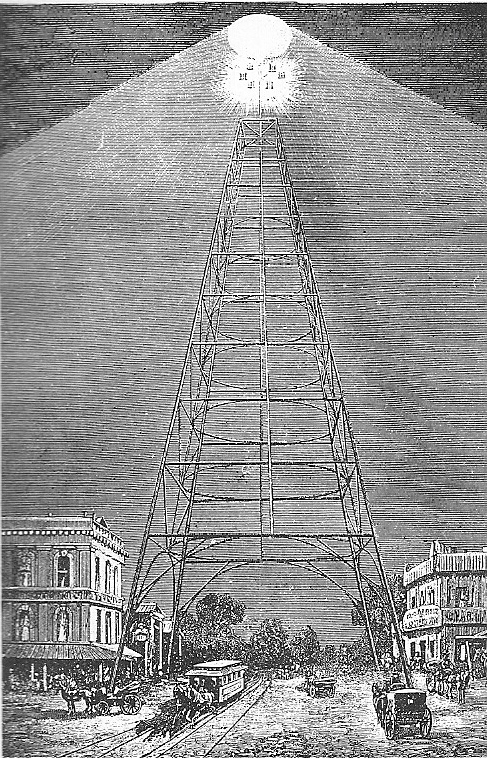

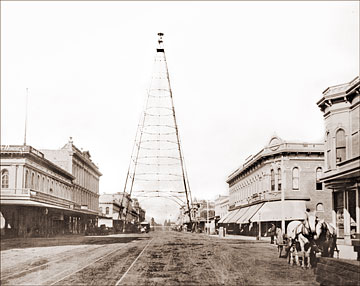

The first fallen structure that I ever admired was a 237-foot tower that once stood at the intersection of Market and Santa Clara Streets in San Jose, California. It was known as the Electric Light Tower and was hurled into the real from a newspaperman’s idealistic vision. James Jerome Owen knew that electric lighting was the future and, on May 13, 1881, he wrote an editorial in the San Jose Daily Mercury calling for the construction of an enormous tower looming over two streets, an electric landmark that would stub out the gaslights, showering evening luster onto the city with the same indomitable force as the sun. It took only seven months for the idea to seize the imagination of locals, and the tower was constructed and lighted by December 13, 1881.

The tower never produced the searing glow that Owen longed for, but it served as a symbol of hope and progress to the people of San Jose. Electricity had only just arrived and the frame of the tower was juiced up by sizzling refulgence. Birds often smacked into its tempting bones, lured by the light, and it is said that policemen cadged a bit of pin money by hawking fallen duck corpses at local establishments. Drunkards often attempted to scale it. Moreover, San Jose had beaten Paris to the punch. Alexandre Gustave Eiffel pilfered the plans and, eight years after Owen’s gigantic tower was raised, Eiffel constructed his own version. This French treachery caused San Jose to sue Paris in 1989 for the century-long appropriation. In the trial, the architect Pierre Prodis claimed that the Eiffel Tower was merely a “trace job” of Owen’s vision. Paris triumphed in the court, but not without the famous engineer’s legacy sullied.

The tower never produced the searing glow that Owen longed for, but it served as a symbol of hope and progress to the people of San Jose. Electricity had only just arrived and the frame of the tower was juiced up by sizzling refulgence. Birds often smacked into its tempting bones, lured by the light, and it is said that policemen cadged a bit of pin money by hawking fallen duck corpses at local establishments. Drunkards often attempted to scale it. Moreover, San Jose had beaten Paris to the punch. Alexandre Gustave Eiffel pilfered the plans and, eight years after Owen’s gigantic tower was raised, Eiffel constructed his own version. This French treachery caused San Jose to sue Paris in 1989 for the century-long appropriation. In the trial, the architect Pierre Prodis claimed that the Eiffel Tower was merely a “trace job” of Owen’s vision. Paris triumphed in the court, but not without the famous engineer’s legacy sullied.

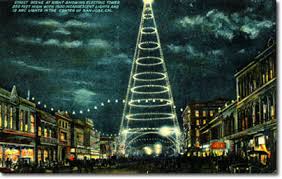

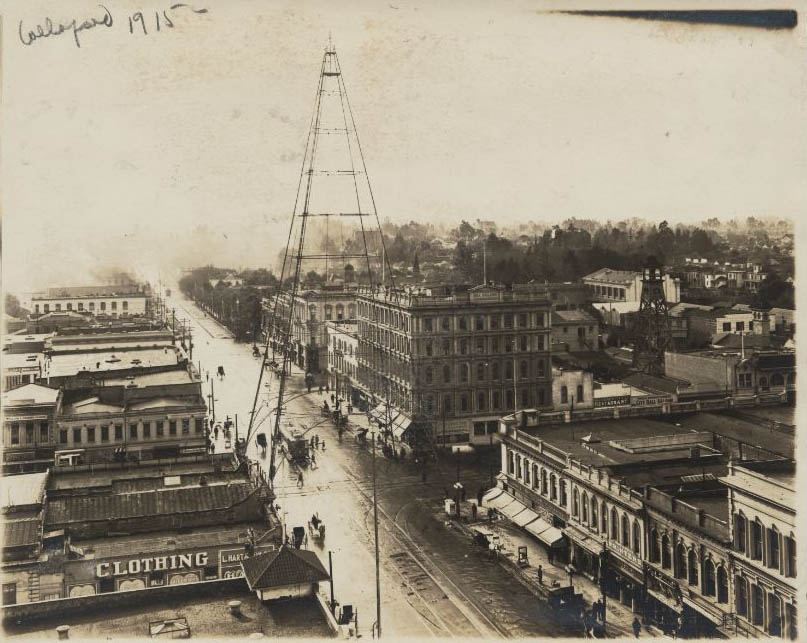

I learned of the tower when I was five, attracted to the pointillist rings glowing on photos and postcards. I was smitten by the great circular aura shooting into the onyx skyscape from the six carbon arc lamps planted at the tower’s peak. And when my parents took me to Kelly Park, I became overcome with tumultuous wonder when my little eyes snagged onto a replica of the tower built in History Park. The replica was only 115 feet tall, recently constructed, and I remember asking the tour guide why it was so small. I had somehow remembered the height of the original, plucking it from some stray placard that most tourists ignored. What was the point of reproducing a tower if you couldn’t put it in the right place or match the previous height? The tour guide, sifting through his mental arsenal for general historical information to answer my question, told me how the original tower fell. Gale force winds had ravaged the tower on December 3, 1915. It was the deadliest part of a vicious storm. The center of the massive metal structure wended and wobbled and, just before noon, pipe and metal poured onto San Jose’s streets. I closed my eyes and began to imagine the beautiful tower destroyed, and I remember silently crying, knowing that the tower’s end was needlessly permanent. I don’t remember the tour guide’s exact words, but there was a peremptory tone in his voice, a suggestion that it was mad folly to build another tower and cause harm to future San Jose residents. San Jose still suffered from wintry winds every now and then. And there was still the possibility, especially given the freak 1976 snowstorm from a few years before, that the tower could do more damage.

I learned of the tower when I was five, attracted to the pointillist rings glowing on photos and postcards. I was smitten by the great circular aura shooting into the onyx skyscape from the six carbon arc lamps planted at the tower’s peak. And when my parents took me to Kelly Park, I became overcome with tumultuous wonder when my little eyes snagged onto a replica of the tower built in History Park. The replica was only 115 feet tall, recently constructed, and I remember asking the tour guide why it was so small. I had somehow remembered the height of the original, plucking it from some stray placard that most tourists ignored. What was the point of reproducing a tower if you couldn’t put it in the right place or match the previous height? The tour guide, sifting through his mental arsenal for general historical information to answer my question, told me how the original tower fell. Gale force winds had ravaged the tower on December 3, 1915. It was the deadliest part of a vicious storm. The center of the massive metal structure wended and wobbled and, just before noon, pipe and metal poured onto San Jose’s streets. I closed my eyes and began to imagine the beautiful tower destroyed, and I remember silently crying, knowing that the tower’s end was needlessly permanent. I don’t remember the tour guide’s exact words, but there was a peremptory tone in his voice, a suggestion that it was mad folly to build another tower and cause harm to future San Jose residents. San Jose still suffered from wintry winds every now and then. And there was still the possibility, especially given the freak 1976 snowstorm from a few years before, that the tower could do more damage.

I didn’t remember the snowstorm because I was an infant at the time. But like the Electric Light Tower, it had been captured in family photographs assembled in blue-covered albums identified sequentially by numbered stickers, so that I could trace the precise moment that the memories of my life aligned with the photographs. I had no memory of the snowstorm, but I had lived through it. I was forming memories of the electrical tower, visions that made it more real than any representation, yet I hadn’t been fortunate enough to be alive during the time of its existence. (I would have similar feelings for the Victorian version of the Cliff House constructed by Adolph Sutro in 1896, a magnificent multiroom palace with sharp gables famously captured in photographs during a thunderstorm. It burned to the ground on September 7, 1907 — another architectural tragedy, another great structure destroyed on a whim.)

I didn’t remember the snowstorm because I was an infant at the time. But like the Electric Light Tower, it had been captured in family photographs assembled in blue-covered albums identified sequentially by numbered stickers, so that I could trace the precise moment that the memories of my life aligned with the photographs. I had no memory of the snowstorm, but I had lived through it. I was forming memories of the electrical tower, visions that made it more real than any representation, yet I hadn’t been fortunate enough to be alive during the time of its existence. (I would have similar feelings for the Victorian version of the Cliff House constructed by Adolph Sutro in 1896, a magnificent multiroom palace with sharp gables famously captured in photographs during a thunderstorm. It burned to the ground on September 7, 1907 — another architectural tragedy, another great structure destroyed on a whim.)

There hasn’t been a year when I haven’t thought about the tower. Yet I wonder how long I can keep its vision alive in my heart and mind. Nobody seems to remember it or care about it outside San Jose. Nobody wants to honor the tower that once attracted international attention. I can’t talk about the Electric Light Tower with anyone, especially on the East Coast. It is, like many funny ideas in the history books, an eccentric and possibly nonsensical idea. But for a decent stretch in history, it held one city together.

There hasn’t been a year when I haven’t thought about the tower. Yet I wonder how long I can keep its vision alive in my heart and mind. Nobody seems to remember it or care about it outside San Jose. Nobody wants to honor the tower that once attracted international attention. I can’t talk about the Electric Light Tower with anyone, especially on the East Coast. It is, like many funny ideas in the history books, an eccentric and possibly nonsensical idea. But for a decent stretch in history, it held one city together.

I am an artist and am working on a design proposal for a painted intersection project in downtown San Jose. I’m enamored of the tower too and it’s the primary image for my proposal. I hope it comes to fruition and will keep you posted on any progress.

Thanks for this terrific post.