Alison Bechdel appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #460. She is most recently the author of Are You My Mother? She has previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #63 and The Bat Segundo Show #250.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

[PROGRAM NOTE: Because this show is so unusual, we feel compelled to offer some helpful cues. At the 7:42 mark, Our Correspondent stops tape. He then offers an explanation for why he did this. At 8:09, the conversation with Ms. Bechdel continues. And then at the 40:34 mark, shortly after hearing some unexpected news from Ms. Bechel, Our Correspondent loosens an outraged “What?” that is surely within the highest pitch points in this program’s history.]

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Wondering if his false self is good enough.

Author: Alison Bechdel

Subjects Discussed: Attempting to ratiocinate on four hours of sleep, Virginia Woolf’s diary entries, Virginia Woolf’s photography, To the Lighthouse as surrogate psychotherapy, Woolf’s “glamour shoot” for Vogue, not doing enough research, attempts by Bechdel to “get her mother out of her head,” the memoir and finding the true self, Donald Winnicott, not being “well-read,” reading Finnegans Wake in a closet, not reading John Updike and Joyce Carol Oates, guilt for not reading everything, encroaching mortality, working a double shift of writing and drawing, only reading the stuff you want to use, “Alison in Between,” tinting skin with retouching ink, tinting much of Are You My Mother? in pink, the futility of writing in a word processing document, comics as a language, ambiguity in comics, Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book, Bechdel’s mother disappearing into a plexiglass dome, depicting origin points of what Bechdel writes and what Bechdel illustrates, living and writing from a place of shame, aggression and psychotherapy, writing about another person as a violation of their subjectivity, Bechdel’s mother’s tendency to read everything as a personal yardstick, how Donald Winnicott to organize one’s life into a book, Bechdel’s desires to cure herself, Bechdel transcribing her mother’s conversations, difficulties in recreating conversations, Bechel’s “apprentice fiction,” vigorous nonfictional expanse, how Love Life turned into Are You My Mother?, Bechdel going to great lengths to avoid the story about her mother, the difficulties of constantly writing about your life, the connections between writing and living, protection from outside voices, Bechdel’s shifting views on herself as an artist, becoming a secret writer, “literary situations,” the strange transformation of cartooning in recent years, how cartooning and other genres have been co-opted as “literature” after being ignored, artistic liberation and oppression, the risks of mainstreaming culture, Samuel R. Delany, being hypocritical progressives on Occupy May Day, the new obligations of artists to a corporate infrastructure, Susan Cain’s Quiet, introverts, obnoxious journalists pushing for personal details, flogging and pimping, the risks of putting yourself up front, being confessional without revealing much, Chester Brown’s Paying for It, Marc Maron’s interview with Matt Graham, telling all on Facebook, Bechdel’s teaching, Roland Barthes’s autobiography, how memoir subsists in a tell-all age, Foursquare, contemplation and narrative nuances, Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows, “the great Internet crackhouse,” Google searches and happenstance, the rabbit holes that emerge when you’re looking for something simple, Hope and Glory, C.S. Lewis’s Narnia, why World War II is an emotional trigger point for Bechdel, therapy and First World problems, Bechdel’s mother’s artistic life, palling around with Dom Deluise, ripping off Keats, the mother’s face as the precursor of the mirror, and whether any author can see herself in a memoir.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Bechdel: I need to have pictures to make the kind of associative leaps that get me through my ideas, that get me through to some kind of conclusion. When I was writing Fun Home, I felt like I had to explain why it was a comic book. Like, oh, there was lots of powerful visual images from my childhood. I grew up in this ornate house. It was important to show that. But I don’t think that’s true. I think I was just trying to accommodate, just trying to make an excuse for why I decided it to be a comic book. But I don’t feel like I need to make that excuse anymore. Comics is a language that I’m learning to be more fluent in. And it helps me to make arguments and arrive at revelations.

Correspondent: As you become more fluent in the language of comics, has it become more ambiguous in some way? Has the ambiguity of the grammar and the language that you have staked your claim on been of help in exploring the ambiguities of life and the ambiguities of some life that is presented on the page?

Bechdel: I feel like I’m always trying to push the distance between the text and the image, the stories that are being described and the scenes and the narration that’s running over it. I’m trying to stretch that as far as I can without losing the reader’s attention. But I love that distance. And I think something powerful can happen in that distance.

Correspondent: Such as what do you think?

Bechdel: Well…

Correspondent: Is there a moment in this book where you felt that you hit that particular power?

Bechdel: Oh, I think of that Dr. Seuss spread, which was a purely visually driven sequence. I’m talking about one of my favorite childhood books, which was Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book.

Bechdel: Oh, I think of that Dr. Seuss spread, which was a purely visually driven sequence. I’m talking about one of my favorite childhood books, which was Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book.

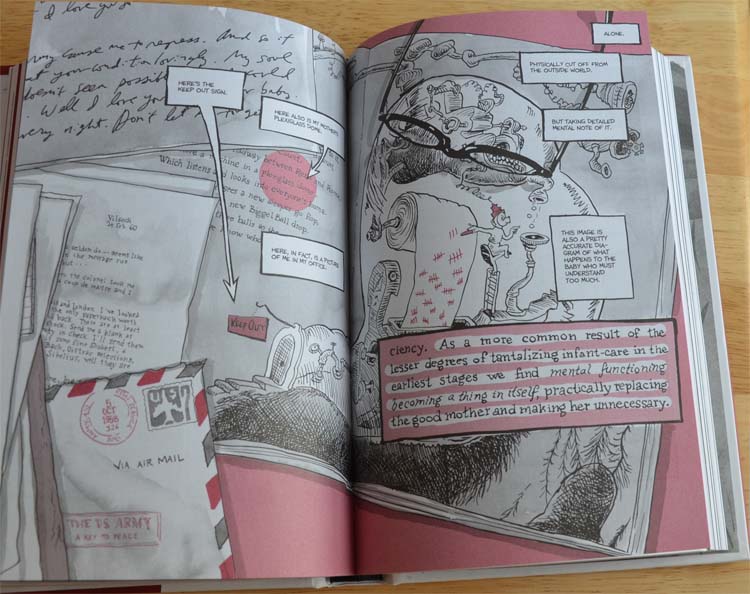

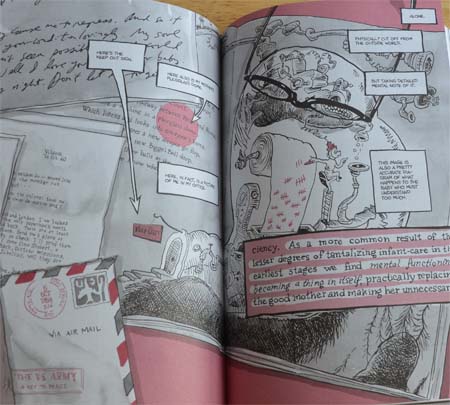

Correspondent: The Plexiglass Dome and all that.

Bechdel: The Plexiglass Dome. With my first therapist, I would always describe my mother as having this plexiglass dome. Like at 9:00 at night, she would disappear in plain sight under this invisible dome, where she would smoke and read and no one could talk to her. She was off duty for the night. And I didn’t realize this. But looking through Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book, the phrase “plexiglass dome” is right there. And it describes this little creature who lives inside a big dome watching everyone else in the world and touting them on a big chart. It’s hard for me even to talk about this stuff. Because I kind of need the visuals. And I think visually.

Correspondent: I’ve got it right here. (hands over the book)

Bechdel: Okay. (flipping through book) But when I was looking at this illustration as an adult, it just was immediately obvious to me that this dome was in the shape of a pregnant…

Correspondent: Pregnant uterus.

Bechdel: It even has a little door that says KEEP OUT. And this is just a sequence of ideas I never would have gotten at without pictures. I’m able to trace its origins in my own childhood drawings. And I’m able to project this metaphorical connection with the womb and my own desire for that kind of primal oneness with my mother that has been forever sundered. But that was visually driven. I couldn’t have come up with that without pictures and visual metaphors.

Correspondent: It’s interesting to me that the origin point very often of what you read is depicted more than the origin point of what you illustrate, or even what you write. I think of the infamous drawing that you do on the bathroom floor in this.

Bechdel: (laughs) Oh god.

Correspondent: A doctor examining a girl. We don’t actually see this. But what’s fascinating is that we actually do see a page of a memoir, a fragment that you wrote, with your mother’s red inkings all over it. Except that is occluded by all these textual boxes of Alison in the present day.

Bechdel: Yeah. My narration overlaying it.

Correspondent: So my question is: why didn’t you portray that drawing in an explicit way? Did you feel that you were more driven by words as a way to find the track here?

Bechdel: Well, sometimes, it’s more powerful not to show an image. In that case, maybe it was a cop out. But I really didn’t have the original image.

Correspondent: Yes, there’s that.

Bechdel: My mother had thrown it out. And I couldn’t replicate my child’s drawing without seeing the original. But that was just a cop out. I was very relieved I didn’t have it. Because I wouldn’t want to show that. It was just — that chapter was so difficult to write. Just revealing that childhood sexual fantasy was excruciating. I was living in just a horrible pit of shame for months as I was working on that chapter. For all of these chapters, whatever old dark emotion I was writing about — shame or depression or grief. All of that would take over my life during the period I was writing about it in a very uncomfortable and disconcerting way.

Correspondent: Is shame a source of comfort for you? I mean, I’m sure not everything here was written in shame. I mean, to my mind, I really like the therapy sessions. Because you draw yourself as just being super-excited to confess. More so, I think. We see the Alison in the therapy sessions. She’s like, “Yes! I’m going ahead and getting my aggression out!” And all this. Aggression, I suppose, or delight must have fueled this in some way. You can’t exclusively draw from a sense of shame to really confront something.

Bechdel: No. There was a whole range of different emotions. And the realization of my aggression was a great breakthrough. Something that I think enabled me to push through and finish writing Fun Home, my first memoir, and that I had to tap into again for this memoir. But my mother — it was a terribly aggressive act. Writing about any real person is such a violation of their subjectivity.

Correspondent: Well, how do you go ahead and honor your mother either during or after this book? I mean, she did review a good deal of it — at least if I’m going by the book here.

Bechdel: Yeah, she did. Well, you know, I feel lucky to have such an interesting and smart mother who cares about writing. Maybe my whole putting myself down about how little I’ve read is like a mother issue. Because my mother reads voraciously. She’s read much more than I do. She keeps up with all the criticism. She reads the London Review of Books. She reads a lot. And I could never stack up to that. So I guess I have to just keep whining about that in public.

Correspondent: But why should that even matter at this point? I mean, that’s the thing that fascinates me. I mean, if this book was your own To the Lighthouse, to free yourself of your mother, I mean, here we are talking about books and I’m like, “Well, Alison, at this point, you have nothing to worry about.” I would think. From a reading standpoint.

Bechdel: All right.

Correspondent: Even considering the mortality thing, which I totally understand. But I think you’re perfectly erudite as it is. You’re certainly more erudite than most Americans, I would say.

Bechdel: I’ll just have to settle for that, I guess.

Correspondent: Settle for that? Why? I mean, why not just be? We were talking about the true self in this, right? What about the true self of the Alison right here?

Bechdel: Maybe it’s just that I used to read so much as a child and I don’t read at that same pace. So I feel that I’m not living up to my image of myself.

Correspondent: Is this the same for drawing? And for art? And for illustration and all that? Do you feel that you’re holding yourself up to any yardstick? Or is it really just…

Bechdel: No, I feel pretty good about my drawing output.

Correspondent: I actually wanted to as you about a number of situations in this book where words are often operating on a different track than the life that is unfolding that you were depicting. I’m thinking, of course, of the “ersatz” argument with your mother while you’re going through Winnicott. Lying in bed with a book, as you have Eloise trying to tell you something that is very vital. And you’re just there with your book. Your mother patching your jeans while you discover the Jungian mother archetype.

Bechdel: Yeah. Those are some scenes where I feel like I really am pushing on that distance and asking a lot of the reader to follow my story, but also listen to my little essayistic digression. And I never quite know if that’s going to work. I hope that it does. Often, it’s sort of a plane to the thing. I’ll try to have a really interesting, compelling scene unfolding in the foreground so that the reader has some patience for these less related thoughts.

Correspondent: Is it a way of compartmentalizing yourself? To come to grips with certain truths? To decide what you’re going to put down and what you’re not going to put down?

Bechdel: No. I’m not sure what it is though. I can’t think of a counterargument to that.

Correspondent: Well, how does someone like [Donald] Winnicott help you in organizing your life?

Bechel: Oh man. Well, Winnicott helped me in organizing the book. But I knew from the beginning that I was fascinated with him, that I wanted to learn more about his ideas. But I didn’t know for quite some time that I would actually use him as some kind of structuring device. Each chapter in the book is organized on a different one of his pivotal theories. So he organized the book. But also I feel like I was trying to vicariously be analyzed by Winnicott. I wanted to be his patient. And so I did that through reading his work. And I haven’t actually thought about this explicitly. And this is the first time I’m trying this out. But I’m creating this attenuated analysis with Winnicott. Comparing myself to other case studies that he talks about. The famous Piggle case of the little girl he worked with. Who was just about my age. And I sort of identify myself with this child. With other people in case studies. Like in his mind and the psyche-soma paper, he talks about a middle-aged woman who just never felt like she was really alive or really present in his life. And I identify myself with her. And through his patients, I’m trying to cure myself.

Correspondent: Cure yourself? Or find points of comparison? Just to have a guide here?

Bechdel: I want to cure myself.

Correspondent: Cure yourself?

Bechel: I’m always trying to cure myself.

Correspondent: Is anybody completely curable? Are you completely curable?

Bechdel: No. But I would like to be more cured.

The Bat Segundo Show #460: Alison Bechdel III (Download MP3)