(This is the seventeenth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: Lord Jim)

“I won’t ruin it for you,” emailed my fellow Modern Library reader Steve, “but so far, that’s the 2nd worst book I’ve read for this project.” And while I was corralling my thoughts and feelings after finishing the latest tome for a project which I now realize (nearly one year after the gauntlet cleaved my happy little picnic table) will take me five to six years, I noticed that Devon S., another trusted Modern Library adventurer, served up only a soupçon more hope: “I don’t know how to judge my indifference to this book. Sometimes books are like calf leather gloves in August: sumptuous wonders of of craftsmanship and texture that we’d appreciate if only we weren’t too tired, too harried, too dull, too careless, too immature, too hot, at that moment.” Maybe so. But when the Brooklyn nights outside are 13 degrees and you’re still wondering why two stuffy high society types (one reappears very sparingly throughout the rest of the book) have chosen the “bronze cold of January” with its shivering swans, of all places, to dish dirt during the oddly loquacious opening of Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart, calf leather gloves in August feel as distant as last year’s milk. What the good Lydia Kiesling will have to say about Bowen is anyone’s guess.

“I won’t ruin it for you,” emailed my fellow Modern Library reader Steve, “but so far, that’s the 2nd worst book I’ve read for this project.” And while I was corralling my thoughts and feelings after finishing the latest tome for a project which I now realize (nearly one year after the gauntlet cleaved my happy little picnic table) will take me five to six years, I noticed that Devon S., another trusted Modern Library adventurer, served up only a soupçon more hope: “I don’t know how to judge my indifference to this book. Sometimes books are like calf leather gloves in August: sumptuous wonders of of craftsmanship and texture that we’d appreciate if only we weren’t too tired, too harried, too dull, too careless, too immature, too hot, at that moment.” Maybe so. But when the Brooklyn nights outside are 13 degrees and you’re still wondering why two stuffy high society types (one reappears very sparingly throughout the rest of the book) have chosen the “bronze cold of January” with its shivering swans, of all places, to dish dirt during the oddly loquacious opening of Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart, calf leather gloves in August feel as distant as last year’s milk. What the good Lydia Kiesling will have to say about Bowen is anyone’s guess.

Death is a novel quite at odds with a reader’s expectations, which is very much to its credit. Here is a book so blithe about its splenetic revelations that a cigarette lighter illuminates a telltale betrayal in the dark of a movie theater, the moment as casual as a chicken’s throat getting sliced on an abattoir assembly line. Yet even with the flashy reveal of a 20th century habit’s fire, Bowen is fixated on the “taut blond silk” of a character’s calf and fingers keeping up “a kneading movement.” If you’re thinking Bowen’s characters come off as positional objects more clay than flesh, then you’re catching on quick. At times, Death reads as if Bowen blossomed her bulb when describing a dining room’s “sideboards like catafalques” or characters who sit “with pencil poised, preparing to make disdainful marks” rather than with internal emotion. Yet even with Death‘s weird fixations on crudely general and somewhat ridiculous maxims (“There are moments when it becomes frightening to realize that you are not, in fact, alone in the world — or at least, alone in the world with one other person”) and carefree racism (“Matchett, who was as strong as a nigger”), I’d be hard-pressed to deny Bowen’s voice. In chronicling the numerous cruelties heaped upon the sixteen-year-old orphan Portia by servants and gentry alike, Bowen commits herself to an unremitting ugliness in a way rarely seen these days outside of a private party hosted by Roger Ailes.

Last year, The Rumpus‘s Charlotte Freeman described how she admired the way in which Bowen refused to save any of her characters. She asked, “Could one publish such a book now? A book in which no one is healed, in which everyone is, in fact, injured by contact with another?” Perhaps the real question to ask is this: Can a sanguine type of any stripe read such a book now? Joanthan Yardley suggested, in his fulsome praise for Death, that “[a] certain measure of experience, of exposure to life’s cruelties and compromises, is necessary for a full grasp of it.” Spoken like an unadventurous pessimist. Yet I didn’t detest the book like Steve, nor did I feel Devon’s indifference. I think there’s some credence to the idea that time and reference was Bowen’s real game with Death. Maybe Death, like many interesting books, is a Rorschach test. And if that is the case, the place to start surely is the reader’s temperament.

I’m not the type who flits through life without kenning that humans can be cruel (and I have had more than my share of this), but my approach is to be cheerful, protectively acerbic if need be. I’d rather believe that everyone — even the scabrous souls who make existence miserable, often without knowing it — has the power to be kind and decent. My earnestness may seem out of place in New York, but this is a city with a population who performs many quiet favors to strangers. And I’ve lived close to four decades with the good apples far outshining those rotten to the core. As Tracy says at the end of Manhattan, “Not everybody gets corrupted. You have to have a little faith in people.” Sensible advice. My disappointment rumbles when people choose to be mean and avaricious and subpar, especially when they do so without any corresponding set of virtues or they are driven by callow opportunism or stomp on other people on the way up or deliberately set out to destroy something dear to a decent person who isn’t doing any harm. Which is not to suggest that I haven’t sinned or that my own sense of what’s right may be another person’s wrong. (And any opportunistic pixie who props herself up as “fair and empathetic” without copping to the possibility that she may be more than a bit hypocritical in blind spots is not to be trusted. Idealogues come in several forms.) I’m not against healthy skepticism or getting revenge (although it’s better to stick with good deeds, when possible), but the idea of swallowing the bitter pill before seeking any delight, or assuming that people are driven first and foremost by malice, strikes me as a needlessly melancholy way to live.

And yet, on the page and from Bowen’s pen, these selfsame qualities are strangely alluring! So if you have a particular type of titivating heart, you may be confused by Elizabeth Bowen. I may protest Bowen’s worldview (and, after listening to this sour lecture broadcast in 1956*, I don’t think I’d want to know her), but I’m fascinated by how she could think this way. Sixteen-year-old Portia has no parents. The only family members she has to turn to are Thomas Quayne, her half-brother some two decades older, and his wife Anna, who is clinging to lingering youth in crueler, pre-Botox days. (She’s so inveterate that she finds Portia’s diary and reads it. One of Death‘s more brutal subtleties is that nearly all of Portia’s private thoughts are read by other characters. Is this Bowen’s way of scolding the reader?) Thomas and Anna send Portia away to a small town — allegedly “by the sea,” but of course not at all — so that they can have their vacation. Even if one accounts for the fact that Thomas works in advertising and has this tendency to stare at nothing “with a concentration of boredom and lassitude,” one ponders why wanton neglect would be the natural state. Yet as Bowen pushes Portia into a bigger mess — with various letters and diary entries spelling further hints of Portia’s despair; no accident that I thought of Jack Womack’s excellent and needlessly neglected novel, Random Acts of Senseless Violence, while reading these parts (Womack was kind enough to respond to my connective enthusiasm on Twitter) — it’s almost as if Bowen’s pushing the limits of how vicious she can be (which is, as it turns out, sometimes more sadistic than Evelyn Waugh). I haven’t even mentioned the disgracefully rakish 23-year-old Eddie, who not only leads Portia into sham chivalric romance, but doesn’t even know how to smooth things over, much less apologize, when he bungles things up. One of the novel’s high points is Eddie hitting the resort town where Portia is staying and causing a cringe comedy disaster that I cannot in good conscience spoil.

There’s some truth to the notion that Elizabeth Bowen may very well be the missing link between Virginia Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness and Iris Murdoch’s masterful fusing of behavioral study and philosophy. Yet as I’ve intimated above, Bowen can be curiously dictatorial and objectifying with her interior monologues:

She was disturbed, and at the same time exhilarated, like a young tree tugged all ways in a vortex of wind. The force of Eddie’s behaviour whirled her free in a hundred puzzling humiliations, of her hundred failures to take the ordinary cue. She could meet the demands he made with the natural genius of the friend and lover. The impetus under which he seemed to move made life fall, round him and her, into a new poetic order at once. Any kind of policy in the region of feeling would have been fatal in any lover of his — you had to yield to the wind. Portia’s unpreparedness, her lack of policy — which had made Windsor Terrace, for her, the court of an incomprehensible law — with Eddie stood her in good stead. She had no point to stick to, nothing to unlearn. She had been born docile. The momentarily anxious glances she cast him had only zeal behind them, no crucial personality.

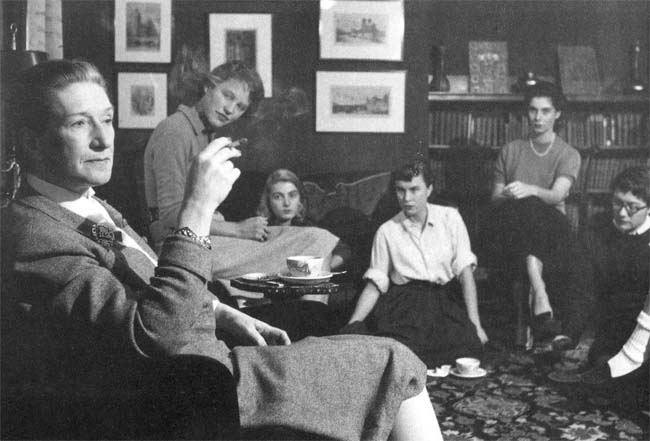

A “young tree tugged all ways in a vortex of wind” sounds like an engineer maneuvering object-oriented data into a massively multiplayer video game universe. And it’s interesting how Bowen shifts from a simile into an entirely different metaphor (“whirled her free in a hundred puzzling humiliations”) before riding with geographic imagery (“the region of feeling,” “No point to stick to”) and concluding this section with highly general and irreversible conditions (“nothing to unlearn,” “born docile,” “only zeal behind them,” “no crucial personality”). While this language certainly mimics a teenage girl’s confused feelings very well, this deliberately incoherent poetic effect (the “new poetic order,” if you will) pushed me away from Portia as I wanted to relate to her. I could admire the language from an external vantage point, but I kept wondering what might have happened if Bowen had dared to give us more of Portia’s heart. Was I meant to read this book much as the young students in the photo above gaze at Bowen? Let me finish my Gauloise, my young pretties, or I shall send you to Samoa to be cooked in a white wine sauce by the cannibals! Fair for the reader or not, nevertheless, I was engaged enough with this novel to want to read more Bowen (still, given the choice, I would rather read more Iris Murdoch). I don’t think I would call The Death of the Heart a masterpiece, but it was good to find a book with a new hook to take me both outside and inside my zone. I never thought the Modern Library would have me affirming certain pockets of sanguinity.

* — Despite Bowen’s grating voice, which is so off-putting that I was compelled to open a window and happily stick my head into the frigid winter air about five minutes in before returning to the last six minutes, the lecture is still quite interesting in what it reveals about Bowen’s methods. She refers to self-conscious expression offered in lieu of description as “character analysis” and has this to say: “Two things may be remarked about the stream of consciousness as a showing of character. It does take time and it deals almost always with prosaic experience. Scenes are reacted to in a highly individual way. I don’t know whether we should ever have, for instance, a stream of consciousness novel about somebody scaling Everest. Because the scaling of Everest is quite exciting enough in itself. In the ordinary stream of consciousness, the excitement, the sense of crisis, resides in the personality. And all the other characters in the novel are likely to be very slightly out of focus.” These sentiments make me want to reach for John D’Agata, Nicholson Baker, Daniel Clowes, or Yannick Murphy and howl to the heavens. Why wouldn’t a mountain climber’s interior monologue be as exciting as the action? And yet I can’t help but marvel over Bowen championing the stylistic dialogue of Henry Green and Ivy Compton-Burnett, whereby there is often no distinction between characters, as a quality which might be altering the form of the novel itself!

Next Up: V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River!