When it came to the circus, even the great Federico Fellini could not resist the personal myth. Fellini’s 1970 quasi-documentary, The Clowns, opened with the young director (portrayed by a child actor) watching workers hoisting a circus tent outside his bedroom window, with each series of grunts producing another incremental rise of the top in the magical night. Ambrose Bierce may have defined circus as the “place where horses, ponies, and elephants are permitted to see men, women, and children acting the fool.” But name another venue where professional fools – especially those who act before more human animals – cause a cinematic genius to reimagine the beginnings of his own allure. The modern circus has endured quite well after Philip Astley. Assuming that you haven’t handed over all four of your ventricles to the great capitalist sham, it remains difficult for any vaguely mischievous soul to countervail the circus’s great charms.

Aaron Schock has largely resisted Fellini’s understandable tendency to reinvent with his striking and quite magical documentary, Circo. The movie depicts a vibrant second-string circus in Mexico – one that has been in some form of existence since the 19th century, but which lacks the resources in the 21st to play the big cities. Nevertheless, you will find motorcycles rolling in the “globe of death” and performers giving it their all as a recording of Alan Silvestri’s Back to the Future theme plays over dim makeshift speakers.

We are told that you never need a house in the circus. And the maxim appears to be largely true. Home is where the heart is. While the family here appears close-knit, despite evidence late in the film revealing interpersonal fissures, those who stay in the circus work very hard, sacrifice vital aspects of their lives for their art, and face increased taxes and costs so that audiences can have a good time. There are some performances where hardly anybody shows at all. But the family still shrink wraps tasty snacks and they give it their all. After all, the show must go on.

Sick days are not an option. Money needs to be produced. When we see one of the trucks containing llamas and tigers break down, we know immediately how unforgiving the economy and the operational expenses will be on the family. It is something we can never truly understand through the film medium, except for those who try to leave the circus and can’t always adopt to the nine-to-five jobs and come back. But coming back is not without its difficulties. The circus life is one where, if you don’t convince a girl to get in the truck when you’re about to leave a stop, romance is a concatenation of ephemeral encounters.

“Without children,” says one man, “there is no circus.” And sure enough, the vehicles carrying the booming announcers roll through the streets of distant domiciles. It draws the enthusiasm of kids who run along the side and beg for tickets and try to schmooze the man at the wheel for a few more.

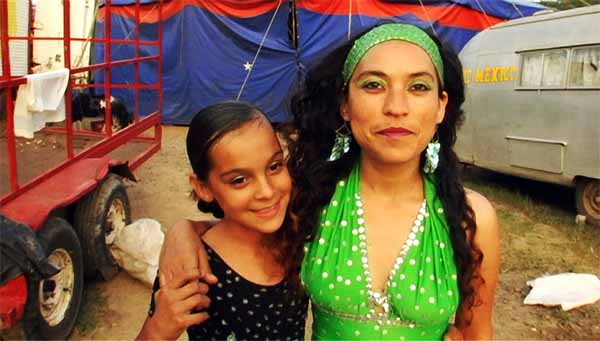

It’s difficult to walk away from this film without being deeply affected by the iridescent streaks that the circus manages to paint upon the most colorless crannies of Mexico. It remains a mystery how much of this is clever cinematography and how much of this is a bona-fide collision. But I don’t think it matters much. Beyond this rich visual charm, Circo movingly puts human faces upon the families who work long days for a few hours of grand entertainment.

For the Ponce family running the Gran Circo Mexico, being a kid means learning gymanstic tricks at every spare moment, and scarfing down tortillas and beans after a hard day of wrangling animals and performing chores and enduring the educational instructions of an uncle sitting on the steps of a trailer. As one family member says, “You have kids to give them everything. And they work too much.” But what kid wouldn’t want to tame a tiger? What kid wouldn’t want to put on a mask and entertain a crowd? There is also Naydelin, one very adorable five-year-old girl who, when leaving the circus for school, still finds delight in learning grammar – even though we know that she’s giving up the rarest on-the-job training imaginable. She feels genuinely apologetic for the young girls who will never know such a world.

Circo comes about as close as a film can get to knowing such a world. The film’s great sense of wonder comes in knowing that nothing here needed to be reinvented. This could not have been easy for the filmmakers and it’s certainly not easy for the audience. Because the people in this film chose the circus life and, against all odds, remained determined to walk on water. And if you can’t get behind that, it’s very possible that you’re not really living.