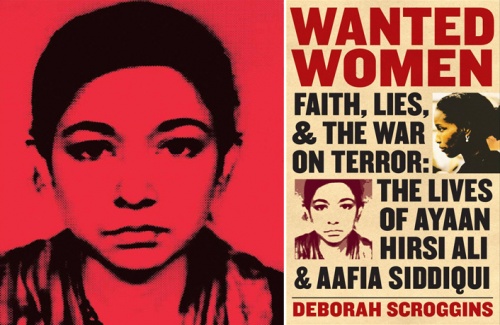

Deborah Scroggins appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #431. She is most recently the author of Wanted Women: Faith, Lies & The War on Terror: The Lives of Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Aafia Siddiqui. My response to Dwight Garner’s New York Times review, which contains more links and information, is also helpful background reading for this interview.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Oscillating between two polar points.

Author: Deborah Scroggins

Subjects Discussed: Salman Rushdie and the Jaipur Literature Festival debacle, India’s political sensitivity, Islamic pluralism, Theo van Gogh’s assassination, why so many intellectual figures supported Ayaan Hirsi Ali (even after revelations of falsehood), Affia Siddiqui’s fundamentalism while a student at MIT and Brandeis, Hirsi Ali’s desire to abolish Article 23 of the Dutch Constitution, Muslim schools in the Netherlands, Hirsi Ali’s belief that all Islam is dangerous, Siddiqui’s close ties to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Siddiqui’s 86 year prison sentence and murky details in the early stages of her capture, the Justice Department not trying Siddiqui on terrorism, Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, how Siddiqui’s treatment has impacted U.S.-Pakistani relations, the Hague spending $3 million a year to protect Hirsi Ali in the United States, the Foundation for the Freedom of Expression, the degree of danger against Hirsi Ali in the U.S., Siddiqui’s lawyers backing off from initial charges that Siddiqui was being tortured in Bagram, Abu Lababa’s claims that Pakistan was going to come under attack from the United States, why Pakistan only selectively observed certain facts relating to Aafia Siddiqui, unchecked claims of Siddiqui has cancer and got pregnant in prison, advantages in not talking with Siddiqui and Hirsi Ali for a dual biography, Scroggins’s efforts to stay objective, Daniel Pearl’s murder, Bernard Henri-Lévy’s claims that there are ties between the ISI and the Deobandi jihadists, speaking with Khalid Khawaja, efforts to steer Scroggins away from Siddiqui, trying to find the truth given so many inconsistent stories and motivations, Yvonne Ridley‘s press conference offering further claims concerning Siddiqui, why Scroggins unthinkingly forwarded a Pakistani journalist’s email to Siddiqui’s lawyers, how lack of journalistic care puts people in danger, Hirsi Ali’s positive qualities, finding the balance between defending extreme free speech and knowing the implications, considerations of nonviolent Islam, connections between Siddiqui and Hirsi Ali, and how extremism feeds upon itself.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I’d like to calibrate this conversation with recent events in India. There was, of course, the whole Salman Rushdie affair at the Jaipur Literature Festival. He gets a report indicating that there are going to be hit men from the Mumbai underworld who are going to assassinate him. So he decides not to go. Then he pulls out. And then Hari Kunzru with various other authors actually read from The Satanic Verses, which is banned in India. Then they have to leave. And then it’s discovered that Rushdie has, in fact, been relying on fabricated police reports, which makes everything extremely interesting. And then, most recently this morning, the latest escapade reaches almost a reductio ad absurdum level in the sense that Jay Leno tells a joke and this is considered a grave offense and they want the government to step in. So all this is happening — as I’m thinking and considering your book, which deals with two key polar figures — Aafia Siddiqui and Ayaan Hirsi Ali — and I’m curious about this. It seems to me that we have an environment in which extremes beget extremes beget extremes. And I’m wondering how understanding figures like Hirsi Ali and Siddiqui leads us to contemplating more Islamic pluralism. Moderation. Or is such a thing possible? Maybe we can start off from there.

Correspondent: I’d like to calibrate this conversation with recent events in India. There was, of course, the whole Salman Rushdie affair at the Jaipur Literature Festival. He gets a report indicating that there are going to be hit men from the Mumbai underworld who are going to assassinate him. So he decides not to go. Then he pulls out. And then Hari Kunzru with various other authors actually read from The Satanic Verses, which is banned in India. Then they have to leave. And then it’s discovered that Rushdie has, in fact, been relying on fabricated police reports, which makes everything extremely interesting. And then, most recently this morning, the latest escapade reaches almost a reductio ad absurdum level in the sense that Jay Leno tells a joke and this is considered a grave offense and they want the government to step in. So all this is happening — as I’m thinking and considering your book, which deals with two key polar figures — Aafia Siddiqui and Ayaan Hirsi Ali — and I’m curious about this. It seems to me that we have an environment in which extremes beget extremes beget extremes. And I’m wondering how understanding figures like Hirsi Ali and Siddiqui leads us to contemplating more Islamic pluralism. Moderation. Or is such a thing possible? Maybe we can start off from there.

Scroggins: Well, absolutely. That could be the whole point of my book. That extremes beget extremes. And there’s no doubt that both of these women — Aayan Hirsi Ali and Aafia Siddiqui — owe their fame to their enemies. Because if Ayaan Hirsi Ali had never been threatened, she would never have been asked to stand for Parliament in the Netherlands. And then if her film collaborator, Theo van Gogh, hadn’t been murdered on the streets of Amsterdam, she wouldn’t have become internationally famous. Aafai Siddiqui, on the other hand, became famous because she was hunted by the CIA and because the CIA and the Pakistani government were actually kidnapping people and holding them in secret prisons, it came to be believed that they were lying when they said that they didn’t know where Aafia Siddiqui was. And no one would believe them, even though in this case they probably were telling the truth.

Correspondent: But how, using the lives of these two women, does a legitimate concern for radical Islam’s suppression of women transform into extremism? I mean, is it the inevitability of the present climate? Whether it be in India or the Netherlands or elsewhere?

Scroggins: Well, I don’t think it has to. I think there are thousands and thousands of women, Muslim women, working to improve women’s rights in the Muslim world who don’t necessarily see a conflict between Islam and democracy and human rights. There’s fascinating things happening as we’ve seen with the Arab Spring. So it doesn’t have to be that way. But in Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s case, she has taken the position that Islam is to blame for the oppression of women in the Muslim world.

Correspondent: All of it.

Scroggins: Yeah. So that’s her stance. And it’s been an enormously popular one in the West.

Correspondent: Why do you think it’s so popular in the West? And why do you think Ayaan Hirsi Ali has managed to attract so many notable intellectual figures? As you point out in the book, Rushdie and Sam Harris author this LA Times editorial. You’ve got, of course, Christopher Hitchens supporting her — three days later, revelations occur — in Slate Magazine. You have Anne Applebaum. And they’re still supporting her — even as it’s discovered that she has lied about her asylum application. Even as she is demanding a 50 million Euro security detail from the EC. Unsuccessfully. I’m curious how a person like this also becomes one of the 100 Most Influential People named by Time Magazine. Is it pure charisma? What is the intellectual value of a figure like Hirsi Ali?

Scroggings: Well, the idea that Islam is responsible for the oppression of women is a very old idea in the West. It goes back hundreds of years. So it’s got a lot of roots here. So when somebody says that, it basically coincides with what people believe. So that’s one reason. I think with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, what really has made her so popular is her incredibly personal story. It’s very inspiring how she tells it. Her coming to the West. Becoming converted to Western ideas. Shaking off Islam. And then being threatened with death for speaking out against it. A lot of people feel very sympathetic to her and feel inspired by her because of that. So I think that’s really why she’s gained such an influential backing. And as to why she got named the 100 Most Influential People, that came right after the murder of Theo van Gogh. And I think it was sort of a sympathy vote on Time Magazine’s part. Because prior to all this, she was a very new junior legislator in the Dutch Parliament. Not somebody who would normally be considered one of the most influential people in the world.

Scroggings: Well, the idea that Islam is responsible for the oppression of women is a very old idea in the West. It goes back hundreds of years. So it’s got a lot of roots here. So when somebody says that, it basically coincides with what people believe. So that’s one reason. I think with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, what really has made her so popular is her incredibly personal story. It’s very inspiring how she tells it. Her coming to the West. Becoming converted to Western ideas. Shaking off Islam. And then being threatened with death for speaking out against it. A lot of people feel very sympathetic to her and feel inspired by her because of that. So I think that’s really why she’s gained such an influential backing. And as to why she got named the 100 Most Influential People, that came right after the murder of Theo van Gogh. And I think it was sort of a sympathy vote on Time Magazine’s part. Because prior to all this, she was a very new junior legislator in the Dutch Parliament. Not somebody who would normally be considered one of the most influential people in the world.

Correspondent: It’s fascinating to me that a good story would be all it would take to ingratiate yourself into the intellectual world. And as we’ve seen with the Rushdie thing, he also fell for a good story as well. I mean, why do you think that narrative seems to trump the investigation? Is it difficult, as you learned over the course of writing this book, to pluck away at the pores, so to speak?

Scroggins: Yes, it is. Because a lot of her story is true. And it is inspiring to people. So that’s a big part of it. Some of the things that have come out — for example, the stories that she told to the asylum authorities. You ask why haven’t her backers backed away from her on account of that. Well, I think it’s because a lot of them feel like they might have done the same thing under the same circumstances. There’s still a lot of sympathy for her, despite the fact. And she has admitted to these lies.

Correspondent: So she’s offered enough remorse in the viewpoint of many of these figures who are supporting her.

Scroggins: Yeah. I don’t know if she’s remorseful. Because she admits that if she hadn’t done it, she would never have become the person that she is today. And it’s hard to see how she would. She would have remained in Kenya.

Correspondent: Well, let’s try to swap between Siddiqui and Hirsi Ali, comparable to your book. When Aafia Siddiqui was getting her doctorate in neuroscience at Brandeis, she actually told her professors that the Koran prefigured scientific knowledge and that the scientist’s job was to discover how the laws of the Koran worked. I’m curious. How was she able to get away with this approach at MIT and Brandeis? I mean, she was able to go ahead and cleave to these religious views and still actually get her education. Can we chalk this up to a profound misunderstanding of Islam at our highest institutions? What of this?

Scroggins: Well, when she started saying these things at Brandeis, her professors were completely shocked. They told me that they had never had a fundamentalist of any description in the program, the neuroscience program at Brandeis. And they actually went back to MIT and they tried to find out. Had she had these views when she had been an undergraduate at MIT? And as far as they could find out, she hadn’t said anything in the science classes at MIT that led anyone to believe that she was a fundamentalist. So that’s one of the mysteries. Whether she sort of changed her views and became more outspoken or whether just nobody paid any attention at MIT. But at any event, by the time that she came to Brandeis, she was done speaking out about this. She was such a brilliant student. She could do all the work, the scientific work, and still make straight As. And her professors still told her, “You’ve just got to keep religion out of it.”

Correspondent: And that was enough.

Scroggins: Yeah.

The Bat Segundo Show #431: Deborah Scroggins (Download MP3)