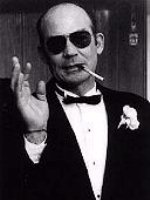

I haven’t read the obituaries. I haven’t read anything. Hunter S. Thompson is gone and his unexpected suicide hit me hard. I was reduced to a blank, morose expression while sitting in a passenger seat in a moving car heading south for some fun. What fun could be had when America’s foremost nihilist and partygoer had decided that enough was enough? It took me about twenty minutes of explaining why Hunter S. Thompson was important and why his work mattered before I could go about my day.

I haven’t read the obituaries. I haven’t read anything. Hunter S. Thompson is gone and his unexpected suicide hit me hard. I was reduced to a blank, morose expression while sitting in a passenger seat in a moving car heading south for some fun. What fun could be had when America’s foremost nihilist and partygoer had decided that enough was enough? It took me about twenty minutes of explaining why Hunter S. Thompson was important and why his work mattered before I could go about my day.

Friends have often noted that I have an older man’s concern with the notable folks who die. But my concerns rest not with mortality, which is inevitable, but the more troubling question of enduring legacy. Who will replace these voices? What other tangible creative things die in the process?

Because Thompson, like all the others, was needed and irreplaceable. The landscape of American letters can never equal the strange mix of chaos and wisdom that Thompson threw into his work with inebriated gusto. It should be noted that Thompson repeatedly read the works of H.L. Mencken and the Book of Revelations in Gideon Bibles when holed up in hotels. Thompson was a man committed to a subjective form of journalism that he believed in with religious fervor, but he never lost sight of the number of the beast painted around Washington.

His work was as shoot-from-the-hip and as inconsistent as any prolific hack. His writings varied from incoherent screeds to astute examinations of American hypocrisy. But at his best (whch was often), he mattered. Thompson stood alone as a courageous voice, and he got people to listen.

A few years ago, Hunter S. Thompson stated repeatedly in interviews, “No one is more astonished than I am that I’m still alive.” I always chalked this up to the Good Doctor defiantly drinking Wild Turkey, imbibing drugs, firing guns into the night, blaring televisions and banging out political diatribes (even howling like a banshee on the commentary track for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas), maintaining the same life that he had built his career upon. Here was a man who had openly settled for Clinton in his collection, Better than Sex, hoping that some spark of true progressivism would endure. Yet two years later, he was the only writer with the balls to eviscerate Nixon upon his death.

In his autumn years, Thompson had settled into a comfortable routine of writing a sports column for ESPN. He had recently married and was keeping busy. But no one can keep a good political junkie down. And it was no surprise when Thompson came out with high hopes for Kerry in Rolling Stone. His essay concluded:

We were angry and righteous in those days, and there were millions of us. We kicked two chief executives out of the White House because they were stupid warmongers. We conquered Lyndon Johnson and we stomped on Richard Nixon — which wise people said was impossible, but so what? It was fun. We were warriors then, and our tribe was strong like a river.

That river is still running. All we have to do is get out and vote, while it’s still legal, and we will wash those crooked warmongers out of the White House.

Thompson must have taken the results in November hard. Harder than anyone. For as much as any of us stupored around for days, feeling as if our last hopes were defeated when four more years of Bush were upon us, Thompson had to feel the pendulum swinging to the right more viscerally than any Poe character.

There’s the famous passage in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in which Thompson describes the death of 1960s idealism:

There was madness in any direction, at any hour. If not across the Bay, then up the Golden Gate or down 101 to Los Altos or La Honda….You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning….

And that, I think, was the handle — that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting — on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave….

So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark — that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.

I always figured Thompson had found a way to go on and accept the hard realities of a nation thumping to a reactionary beat. And maybe he did for a while.

But make no mistake: despite Thompson’s ultimate answer to the predicament, that river is still very much running. And Thompson’s work will endure. The question now is this: Who has the courage to pick up the slack?