Her 37-year-old boyfriend was passed out on the fraying sofa. Too much CBD. And he had only had one gummie. But, hey, it was legal now, wasn’t it? The copy editor looked at her sexually inexperienced boyfriend. She was not inexperienced. But her boyfriend’s body now resembled a fuselage with four stringy limbs in lieu of wings. So she was bored. And angry. Very angry. Despite the regular CBT sessions, the fury had somehow calcified and strengthened in her fifties.

A lifetime of perceiving nothing but disappointment will do that to a miserable person. Just look at Donald Trump, Jr.

Aside from her much younger boytoy, the copy editor’s life was largely joyless. She was a frustrated novelist working in a throwback publishing joint adhering to the finest workplace standards that 1998 had to offer. All handwritten work. It would be so much easier to do it electronically! And she tried to keep the peace in the office. She so wanted to be liked. But she knew that most of her five co-workers hated her. She didn’t know the exact number. Everyone, after all, played a chess game. It was all obliging smiles in the cubes and teenage titters during some of the post-work happy hour sessions that she’d reluctantly attended to show her fellow drones that she was a team player. But she knew they were talking about her behind her back. And it filled her with hate.

Hate. Forget about what Bukowski had written about it. Oh, she hated that misogynistic dirtbag. But Bukowski was small-time. Her hate was in the big time. It was the kind of hate that is impossible to shake off past the age of fifty, when you can’t find happiness or career fulfillment and your boyfriend’s mom somehow ends up being eight years older than you.

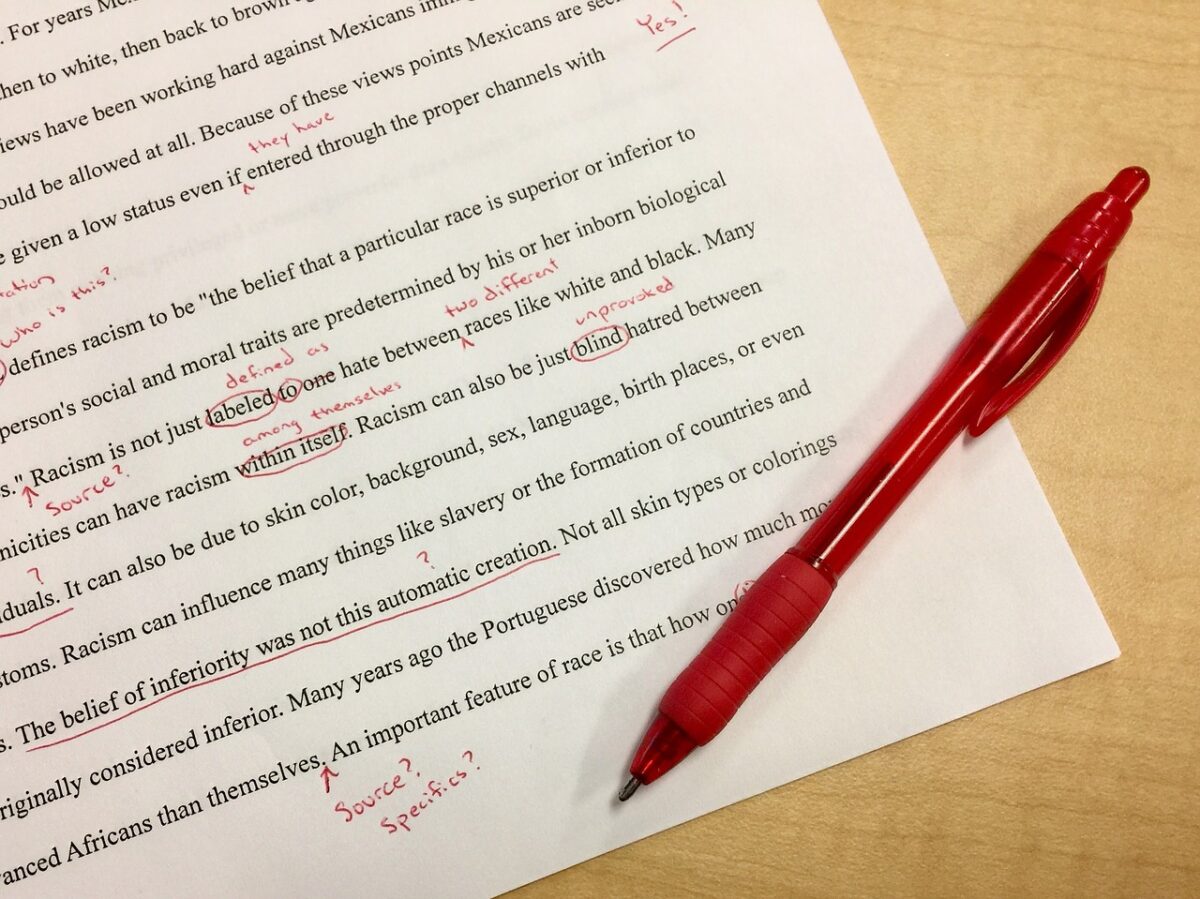

She had learned fairly fast that you needed a grandiose hate to work as a copyeditor. The copyeditor was the sworn enemy of the writer. Even the polite and obliging ones who had boned up on Strunk & White much like law students prepping to take the bar.

Hate was the greatest currency in the publishing industry. I mean, she had to spend all her long dull afternoons striking her pencil against ever-thinner sheets, masticating upon the eraser as she bemoaned yet another badly written piece from yet another doddering writer. A younger writer.

She had more of that to face tomorrow. But tonight was a different story. No, tonight, she would look for a main character. There was always a main character: someone who the Internet was presently ganging up on. And if she could find tonight’s main character, she would summon every ounce of hate she could about a stranger she didn’t know.

She hit TikTok, Twitter, Metafilter, the Fediverse, and Blue Sky. Where was he? Tonight’s main character? Where the fuck was he? And then she saw him. Or rather someone who had once been the main character ten years ago. A comment from that turd.

Did emeritus status apply to main characters? Sure. Why not?

And she moved in. Summoning all the hate she had in the tank. Because she didn’t have love. I mean, what she doled out to the 37-year-old was little more than the usual cultural reference bullshit, which always worked for younger and more gullible types, but never men her age. What she doled out to him was not love, but rather the very strong like that the dating scene in her city was all about. The very strong like that gives you the loophole to say “We’re moving in different directions” at brunch while one of you sobs uncontrollably after making the unfortunate mistake of catching feelings.

And he was there. His prose was still the same. Still hopped up on ten-cent modifiers and crunchy vitriol. It had to be that fucker. Sure, what she knew about him had happened ten years ago, but let the fucker die. Her fingers banged on the keyboard like thugs pelting crouched innocents with steel baseball bats. Kill him with words. Did she know a guy who knew a guy who could really kill him? Oh, she’d like that very much. The dopamine like that comes from hate!

She claimed that nobody liked him and that there were people far more successful than him. And that he would do nothing and be nothing.

What she didn’t know was that he was something.

There!

And she logged off. And she was bored and angry again.

But the subject of her hate was not angry at all. He had built up his own dossier on this troll over the course of a car ride in which he had little else but his phone for company and he had found her. And he decided to spin some of this into a goofy story and laugh his ass off while writing it, knowing that the copy editor could not know what he knew. Because in his tale, he had only doled out only a small parcel of the considerable information she had revealed about herself. Now if he were a cruel man, which he really wasn’t, he would have sent this dossier to human resources so that they would know the full extent of her abusive online behavior: the messages etched with the telltale sentences of self-loathing and hate directed towards other people. But, no, he didn’t want to get her fired. He only wanted to settle the score with the tale.

Now maybe this mischievous writer is talking about someone real. Or maybe not. Maybe some of the details are fudged. Maybe not. A writer draws from his own experience and weaves lies into the mix to get you to care about subjects that you would normally not give a fuck about. A writer also knows what questions to ask, what phone calls and emails to make, what people will be on his side, and, perhaps most vitally, he knows that anyone who is so keenly fixated on a perceived enemy likely has other enemies because of the same glaring character flaws. (Writers, in this writer’s experience, tend to be the easiest marks. This writer, however, while taking egregiously gauche liberties by referring to himself in the third person, is not arrogant enough to discount himself as a mark.)

But, in the end, we ultimately know nothing about people we haven’t met or taken the trouble to know. And without that, all words are fiction marked up by a perfunctory shadow equally meaningless in her rage.