On April 22, 2014, Slate published a long, intellectually reprehensible, and dangerously ignorant article written by Michael Agresta, a self-described “writer and critic” who is such a condescending simpleton that he once compared Lena Dunham’s artistic growth with “a kid playing with this incredible new toy.” The true child is Agresta, who has opined on the state of public libraries with the consummate acumen of a competitive eater who lacks time to taste the hot dogs he stuffs down his gargantuan maw in his rush to hog the questionable spotlight. To say that Agresta gets public libraries very wrong is an understatement. It is like saying that Brad Paisley does not understand racism or Jenny McCarthy does not understand science. For this puffed up little Fauntleroy willfully insinuates, through the hack’s lazy technique of Googling one solitary link to support each foggy point emerging from the dim mist of an addled mind, that public libraries don’t have much of a shot at evolving in a digital age, even as he fails to pore through the considerable journalistic ink revealing what they’ve accomplished already and how many of these digitally inclusive achievements are rooted in principles more than a century old.

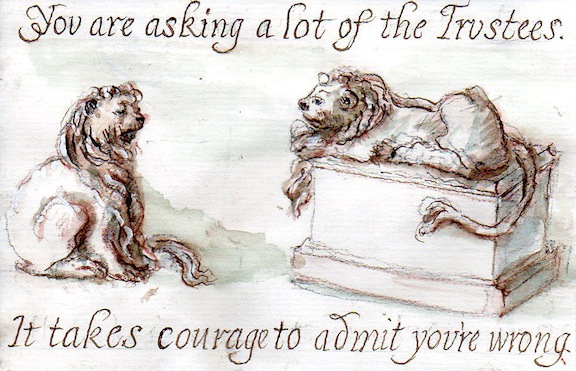

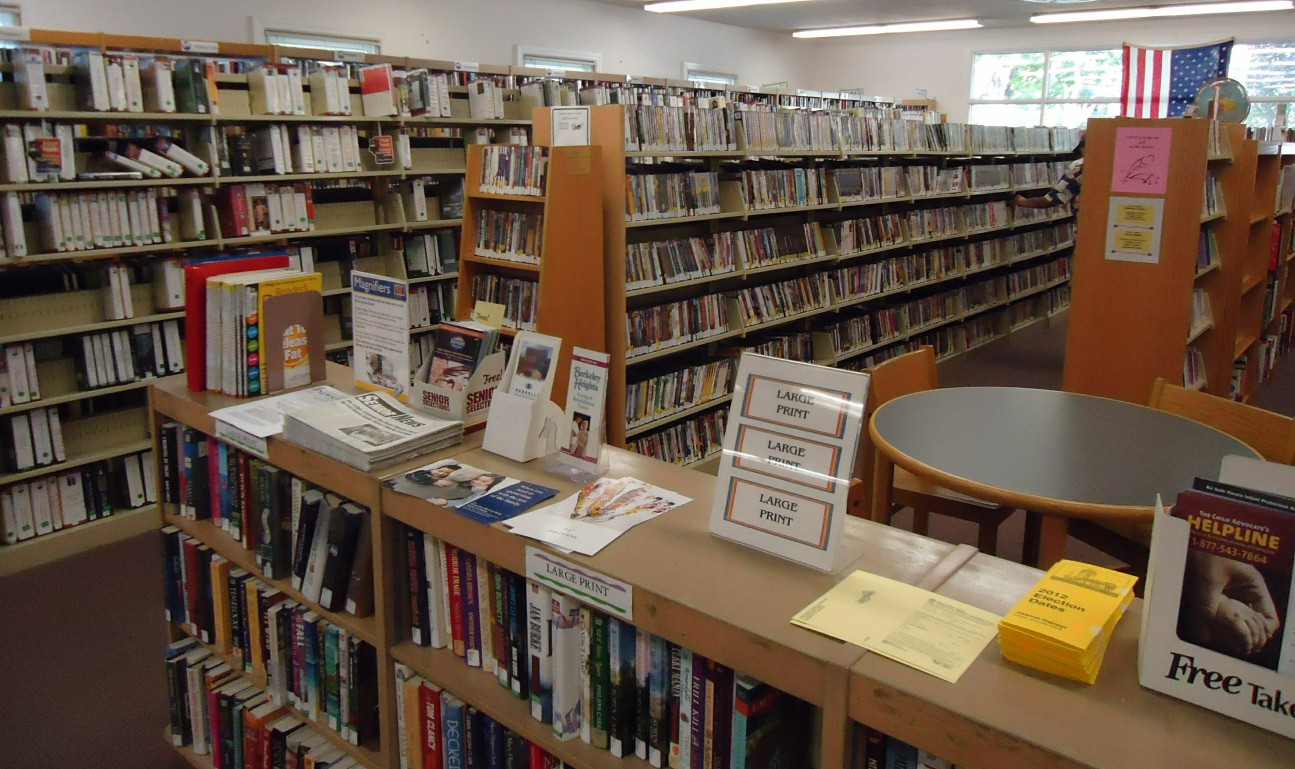

Agresta points to the NYPL’s present Central Library Plan (see my previous reporting), which threatens to shutter the Mid-Manhattan and SIBL branches while uprooting the main branch’s unprecedented research division in the Rose Reading Room, as something which would merely invite physical collapse. What he fails to consider is how shifting the research collection from beneath the main library to a New Jersey storage facility will cause considerable delays when any member of the public requests a special item (to say nothing of how the new architectural plan hopes to accommodate a heightened influx of visitors; all this was chronicled by The New York Times in 2012 but don’t count on Michael “I’ve Got a Slate Sudoku Puzzle to Fill In” Agresta for due diligence). He wrongly and smugly assumes, without bothering to look up the facts or talk with any public officials, that a library without books “seems almost inevitable,” even when the actual facts reveal regular people checking out physical books at the NYPL more than ever before: total circulation at 87 branches has risen 44% since 2008. This is because Agresta is not a journalist. He is a prevaricating muttonhead, little more than a dimebag propagandist, writing tendentious pablum that, like most of the rubbish published in Slate’s godforsaken cesspool, contributes to cultural dialogue much as rats enhance apartments.

Agresta points to the NYPL’s present Central Library Plan (see my previous reporting), which threatens to shutter the Mid-Manhattan and SIBL branches while uprooting the main branch’s unprecedented research division in the Rose Reading Room, as something which would merely invite physical collapse. What he fails to consider is how shifting the research collection from beneath the main library to a New Jersey storage facility will cause considerable delays when any member of the public requests a special item (to say nothing of how the new architectural plan hopes to accommodate a heightened influx of visitors; all this was chronicled by The New York Times in 2012 but don’t count on Michael “I’ve Got a Slate Sudoku Puzzle to Fill In” Agresta for due diligence). He wrongly and smugly assumes, without bothering to look up the facts or talk with any public officials, that a library without books “seems almost inevitable,” even when the actual facts reveal regular people checking out physical books at the NYPL more than ever before: total circulation at 87 branches has risen 44% since 2008. This is because Agresta is not a journalist. He is a prevaricating muttonhead, little more than a dimebag propagandist, writing tendentious pablum that, like most of the rubbish published in Slate’s godforsaken cesspool, contributes to cultural dialogue much as rats enhance apartments.

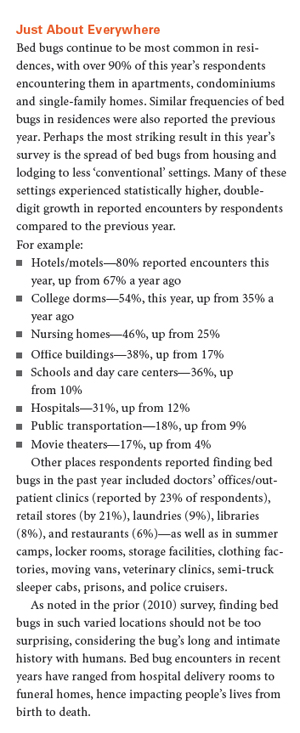

While Agresta is right to point to (without citing it) the ALA’s 2011-2012 Public Library Funding & Technology Access Study’s alarming statistic that more than 40% of states have reported decreased public library support three years in a row, he hasn’t thought to contact the ALA to determine if this trend has continued. By contrast, it took me all of two minutes to contact the ALA’s Office for Research and Statistics. I got the current statistics 90 minutes later from a very helpful man named R. Norman Rose. It turns out that, in FY 2013, states reported that they were having an easier time soliciting funds for public libraries. Rose was good enough to inform me that the new report will be up on Monday. Agresta mischaracterizes the Pennsylvania Senate vote in which the Free Library of Philadelphia came close to shuttering. Active mobilization from the public — more than 2,000 letters directed at state legislators — prevented the so-called “Doomsday” Plan C from being enacted. In other words, the library is far from dead in America. A very active public is preserving it from hostile political forces and any dispatches about its future need to take this activism into account. Agresta then points to 200 public libraries shutting down in the United Kingdom without pointing to the far more interesting problem: nobody seems to know how many public libraries in the United States have closed.

While Agresta is right to point to (without citing it) the ALA’s 2011-2012 Public Library Funding & Technology Access Study’s alarming statistic that more than 40% of states have reported decreased public library support three years in a row, he hasn’t thought to contact the ALA to determine if this trend has continued. By contrast, it took me all of two minutes to contact the ALA’s Office for Research and Statistics. I got the current statistics 90 minutes later from a very helpful man named R. Norman Rose. It turns out that, in FY 2013, states reported that they were having an easier time soliciting funds for public libraries. Rose was good enough to inform me that the new report will be up on Monday. Agresta mischaracterizes the Pennsylvania Senate vote in which the Free Library of Philadelphia came close to shuttering. Active mobilization from the public — more than 2,000 letters directed at state legislators — prevented the so-called “Doomsday” Plan C from being enacted. In other words, the library is far from dead in America. A very active public is preserving it from hostile political forces and any dispatches about its future need to take this activism into account. Agresta then points to 200 public libraries shutting down in the United Kingdom without pointing to the far more interesting problem: nobody seems to know how many public libraries in the United States have closed.

From such dubious figures and distorted facts, Agresta concludes that we are apparently living in an “era to turn its back on libraries,” and he has the effrontery to pull the librarian’s answer to Godwin’s Law out of his chintzy pauper’s hat: the burning of the Library of Alexandria. After shuffling various apocryphal versions of the centuries-old story behind the conflagration like a lonely salesman playing solitaire in a motel room, Agresta then makes the reductionist conclusion that “even the smallest device with a Web browser now promises access to a reserve of knowledge vast and varied enough to rival that of Alexandria.” This is the foolish statement of a blinkered man who has never set foot in special collections, much less considered how books published only a few decades ago can quickly go out of print, often without a digital backup. As someone who sifted through invaluable special collections papers that nobody had touched in two decades only last week, I find Agresta’s conclusion risible. Agresta also doesn’t seem to understand that paper ages and that librarians exact tremendous care to keep invaluable archives preserved. (As scholar Sarah Churchwell informed me in an interview in February, Princeton has kept its F. Scott Fitzgerald papers so tightly sealed that not even the most fastidious historians are allowed to touch its pages.) And while digitization certainly helps when the original source isn’t available (and can often reinvigorate existing collections much as the NYPL Lab’s Menus and Map Warper pages do), not every piece of paper is going to get digitized. Libraries thrive when print and digital systems come together. The mistake by arrivistes like Agresta is when foolish rhetoric is trotted out in lieu of the facts:

From such dubious figures and distorted facts, Agresta concludes that we are apparently living in an “era to turn its back on libraries,” and he has the effrontery to pull the librarian’s answer to Godwin’s Law out of his chintzy pauper’s hat: the burning of the Library of Alexandria. After shuffling various apocryphal versions of the centuries-old story behind the conflagration like a lonely salesman playing solitaire in a motel room, Agresta then makes the reductionist conclusion that “even the smallest device with a Web browser now promises access to a reserve of knowledge vast and varied enough to rival that of Alexandria.” This is the foolish statement of a blinkered man who has never set foot in special collections, much less considered how books published only a few decades ago can quickly go out of print, often without a digital backup. As someone who sifted through invaluable special collections papers that nobody had touched in two decades only last week, I find Agresta’s conclusion risible. Agresta also doesn’t seem to understand that paper ages and that librarians exact tremendous care to keep invaluable archives preserved. (As scholar Sarah Churchwell informed me in an interview in February, Princeton has kept its F. Scott Fitzgerald papers so tightly sealed that not even the most fastidious historians are allowed to touch its pages.) And while digitization certainly helps when the original source isn’t available (and can often reinvigorate existing collections much as the NYPL Lab’s Menus and Map Warper pages do), not every piece of paper is going to get digitized. Libraries thrive when print and digital systems come together. The mistake by arrivistes like Agresta is when foolish rhetoric is trotted out in lieu of the facts:

If the current digital explosion throws off a few sparks, and a few vestigial elements of libraries, like their paper books and their bricks-and-mortar buildings, are consigned to flames, should we be concerned? Isn’t it a net gain?

Agresta then attempts to paint the Carnegie libraries as “the backbone of the American public library system” without pointing to one vital impetus behind the Scotsman’s philanthropy: Carnegie wanted libraries to be the most striking structures in small communities from both an architectural and communal standpoint. Early Carnegie libraries, such as the Free Library of Braddock, had recreational facilities and billiard tables on the first floor. As David Nasaw describes in his biography of Carnegie, Carnegie wanted these libraries to be perfect. The Pittsburgh library alone set aside space for a natural history museum, an art gallery, and a music hall, and involved one of the largest nationwide architectural contests of its time, involving 102 entries from 96 architects in 28 cities. Agresta’s boorish suggestion that libraries resembling strip malls are a continuation of Carnegie’s grand ideals is not only incorrect but an act of vulgar complacency, especially when this foolhardy Slate scribe has the audacity to suggest that “design benefits were ancillary, of course, to the fundamental purpose of the Carnegie libraries.” Further, one can see the communal legacy of Carnegie’s library in Houston today, with its cooking classes, toddler yoga, Photoshop classes, and afternoon movies. In other words, libraries have been “experimenting” with “maker spaces” for more than a century, not recently as Agresta claims. Agresta’s suggestion that wondrous projects highlighted by the Library as Incubator Project are a response to digital perils is quickly eradicated once one visits the Project’s About page. While digital collections are highlighted (as they naturally would in any library in 2014), the Project’s primary purpose is to encourage collaboration between libraries and artists. But that doesn’t stop Agresta from ending his paragraph with this preposterous zinger, parroting the “eloquent” Caitlin Moran:

Agresta then attempts to paint the Carnegie libraries as “the backbone of the American public library system” without pointing to one vital impetus behind the Scotsman’s philanthropy: Carnegie wanted libraries to be the most striking structures in small communities from both an architectural and communal standpoint. Early Carnegie libraries, such as the Free Library of Braddock, had recreational facilities and billiard tables on the first floor. As David Nasaw describes in his biography of Carnegie, Carnegie wanted these libraries to be perfect. The Pittsburgh library alone set aside space for a natural history museum, an art gallery, and a music hall, and involved one of the largest nationwide architectural contests of its time, involving 102 entries from 96 architects in 28 cities. Agresta’s boorish suggestion that libraries resembling strip malls are a continuation of Carnegie’s grand ideals is not only incorrect but an act of vulgar complacency, especially when this foolhardy Slate scribe has the audacity to suggest that “design benefits were ancillary, of course, to the fundamental purpose of the Carnegie libraries.” Further, one can see the communal legacy of Carnegie’s library in Houston today, with its cooking classes, toddler yoga, Photoshop classes, and afternoon movies. In other words, libraries have been “experimenting” with “maker spaces” for more than a century, not recently as Agresta claims. Agresta’s suggestion that wondrous projects highlighted by the Library as Incubator Project are a response to digital perils is quickly eradicated once one visits the Project’s About page. While digital collections are highlighted (as they naturally would in any library in 2014), the Project’s primary purpose is to encourage collaboration between libraries and artists. But that doesn’t stop Agresta from ending his paragraph with this preposterous zinger, parroting the “eloquent” Caitlin Moran:

It’s easy to imagine how a local institution built on these sorts of programs could continue to serve as hospital of the soul and theme park of the imagination long after all the paper books have been cleared away.

Even when Digital Public Library of America founder Dan Cohen tells Agresta, “We love the idea of making a connection between the digital and physical realm,” Agresta fails to ken the DPLA’s purpose, as clearly delineated on its About page. The DPLA’s chief goal isn’t to replace the physical library with the digital one. It is to provide digitized materials to other libraries in a valiant attempt to “educate, inform, and empower anyone in current and future generations.” There is nothing within this mission statement which suggests, as Agresta puts it, a “revamped” set of library ideals for the digital age. But don’t tell that to Agresta, who saves one of his most officious insults for the hardworking librarians who are an unspeakably invaluable part of what keeps libraries going.

Agresta waxes priapic about “book-fetching robots” at the Hunt Library that are similar to the ones “used by companies like Walmart at distribution centers,” as if Walmart was the more ideal model for libraries than the beautiful Beaux Arts edifices carefully considered by Carnegie. But for all of the BookBot’s organizational virtues, the sterile stacks aren’t allowed to be touched by humans, which means that any accidental discoveries must be performed through Virtual Browse.

As the above video demonstrates, with Virtual Browse, you can’t just pick a random book off of these shelves and flip through it. Instead, you have to do so through cold and clinical clicks through a web interface. Moreover, the BookBot is, at $4.5 million, a colossal waste of money, especially since it only returns about 800 books per day — the same work that two full-time students can do. Wouldn’t that money have been better spent on books or programs or top-notch librarians?

When high-tech systems this costly and this inefficient represent the professed future, and when Agresta cannot be arsed to do the math, Agresta’s suggestion that books are “making a quiet last stand” is both ignorant and laughable. And yet in presenting such a partial, incomplete, and uninformed tableau of the current library situation, especially in relation to the Central Library Plan, Agresta’s disgraceful article willfully twists the truth about a very important battle for communal public space into a presumed defeat. This is vile and irresponsible journalism that deserves nothing less than contempt. Michal Agresta should never be allowed to write a longform article on any subject again and the dimwitted editor who signed off on this unvetted and prepossessed drivel should be mercilessly flogged in the court of public opinion just outside the Columbia Journalism Review offices.

Johnson: The Internet is in the library. Google is in the library. The librarians know how to use that. So you go to those public computers in the library. You have a librarian who can not only do Google, but who can also tell you, point you to any number of other resources that are not included in Google, or that are very difficult to get to through Google. It seems like Google is so simple. “It’s so simple even your grandmother can use it,” is the way it was described to me. Yeah, it’s brilliant for getting the quick hit on the restaurant in the Village that you want to have dinner at. There’s the address. There’s the phone number. There’s the little Google map that will get you there. But when you are actually trying to track back. When I have a clipping of a newspaper, and I’m trying to find the digital version of that, I get lost sometimes. It can’t find it. The bread crumbs don’t take you to where you know it has to be. And I’ve had librarians who have actually shown me how to wend my way through Google, which is, after all, full of redundancies, not weighted in terms of date. You need to put your heavy boots on to wade through it sometimes.

Johnson: The Internet is in the library. Google is in the library. The librarians know how to use that. So you go to those public computers in the library. You have a librarian who can not only do Google, but who can also tell you, point you to any number of other resources that are not included in Google, or that are very difficult to get to through Google. It seems like Google is so simple. “It’s so simple even your grandmother can use it,” is the way it was described to me. Yeah, it’s brilliant for getting the quick hit on the restaurant in the Village that you want to have dinner at. There’s the address. There’s the phone number. There’s the little Google map that will get you there. But when you are actually trying to track back. When I have a clipping of a newspaper, and I’m trying to find the digital version of that, I get lost sometimes. It can’t find it. The bread crumbs don’t take you to where you know it has to be. And I’ve had librarians who have actually shown me how to wend my way through Google, which is, after all, full of redundancies, not weighted in terms of date. You need to put your heavy boots on to wade through it sometimes.