There are eight million year-end lists in the naked city. Why the hell do we need another one? Well, I made every effort to keep my trap shut on this dog and pony show for many weeks, figuring that fine minds and excitable souls would ensure that the right butterflies landed in the net. But a number of novels that challenged me, knocked me in the gut, or opened my eyes to the world in new ways have been left behind by tepid tastemakers who wouldn’t know the glorious rush of literature if the late great Harry Crews ran at them with a rifle and a pack of wild dogs. So I feel it my duty as a book lover to weigh in. I read nearly two hundred books in 2012. By a stroke of good fortune, I was able to interview every author who made this list. If you would like to hear these authors in conversation, feel free to click on the links. In the meantime, let’s rock and roll.

Megan Abbott, Dare Me: Before The Millions devolved into an unreadable circlejerk for risk-averse snobs, I tried to impart to these mooks why Megan Abbott was the real deal, pointing out how Abbott’s sentences employed a chewy and often operatic rhythm that was often the only way to deal with the dark edges of existence. But Abbott’s latest novel about cheerleading pushes her distinct voice further with a rich collection of wildly inventive verbs (“Everybody whoops and woohoos, jumping on the bleachers, grabbing each other around the necks like the ballers do”) that will make you wonder how you missed so much beyond the football games. She writes defiantly against the ironic or the ideal cheerleader, but her astute and enthralling observations about teens pushing themselves to their physical limits, often without parents and often with deadly adults entering their lives, left me pondering why nobody went there quite like this before. I’m very glad that Abbott is still on the case. (Bat Segundo interview with Abbott, August 2012)

Megan Abbott, Dare Me: Before The Millions devolved into an unreadable circlejerk for risk-averse snobs, I tried to impart to these mooks why Megan Abbott was the real deal, pointing out how Abbott’s sentences employed a chewy and often operatic rhythm that was often the only way to deal with the dark edges of existence. But Abbott’s latest novel about cheerleading pushes her distinct voice further with a rich collection of wildly inventive verbs (“Everybody whoops and woohoos, jumping on the bleachers, grabbing each other around the necks like the ballers do”) that will make you wonder how you missed so much beyond the football games. She writes defiantly against the ironic or the ideal cheerleader, but her astute and enthralling observations about teens pushing themselves to their physical limits, often without parents and often with deadly adults entering their lives, left me pondering why nobody went there quite like this before. I’m very glad that Abbott is still on the case. (Bat Segundo interview with Abbott, August 2012)

Paula Bomer, 9 Months: Ayelet Waldman may have kickstarted the conversation about bad mothers a few years ago, but Bomer actually has the courage to chase maternal judgment through the pain and hilarity of its truths rather than attention-seeking pronouncements. 9 Months follows Sonia, a pregnant mother who boldly leaves her husband and even goes so far to have carnal relations with a Colin Farrell-like trucker. You could call 9 Months a Gaitskillian picaresque tale, but this doesn’t do justice to Bomer’s fierce and funny insights into how motherhood’s perceptions change from region to region, how judgment has a way of stifling a pregnant woman’s career track, and the casual cruelty of solipsistic singles who can’t understand these finer distinctions. (Bat Segundo interview with Bomer, August 2012)

Catherine Chung, Forgotten Country: This devastating and deeply visceral debut about a South Korean family fleeing to the Midwest has so many rich observations about identity, figurative ghosts, reflections you can’t escape in the existential mirror, and the pros and cons of family unity that it’s difficult to convey just how good it is. Roxane Gay suggested that the manner in which the narrator’s sister Hannah removes herself from her family “takes your breath away while it breaks your heart.” But this novel somehow manages to capture joy during these emotional moments, even while confronting cruelty, racist masks, and premonitory violence. Chung’s characters are real because we come to feel their explicit and implicit pain, the type of qualities found in nearly every family. I’m baffled by how this wonderful novel was so overlooked. (Bat Segundo interview with Chung, March 2012)

Catherine Chung, Forgotten Country: This devastating and deeply visceral debut about a South Korean family fleeing to the Midwest has so many rich observations about identity, figurative ghosts, reflections you can’t escape in the existential mirror, and the pros and cons of family unity that it’s difficult to convey just how good it is. Roxane Gay suggested that the manner in which the narrator’s sister Hannah removes herself from her family “takes your breath away while it breaks your heart.” But this novel somehow manages to capture joy during these emotional moments, even while confronting cruelty, racist masks, and premonitory violence. Chung’s characters are real because we come to feel their explicit and implicit pain, the type of qualities found in nearly every family. I’m baffled by how this wonderful novel was so overlooked. (Bat Segundo interview with Chung, March 2012)

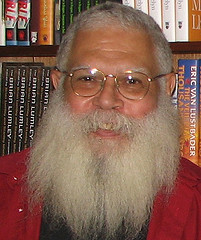

Samuel R. Delany, Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders: It’s easy to understand why so many timid souls couldn’t make their way through this bold, long, and ambitious book. The book bombards the reader with so much sex, sex, and more sex that the reader is forced to come to grips with this as a way of life, even if the reader doesn’t share the desire for cock cheese or coprophagia. Yet it’s a profound mistake to dismiss a book, as one vanilla urchin did, because you lack the courage to push beyond your comfort zone. Delany’s opus may seem to be a repetitive depiction of a couple fucking, but the patient and careful reader will discover a surprisingly moving book about growing older, how underground subcultures are increasingly ignored, and how history is not so much about one person’s overnight success but sum of brave gestures from strangers. (Bat Segundo interview with Delany, May 2012)

Samuel R. Delany, Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders: It’s easy to understand why so many timid souls couldn’t make their way through this bold, long, and ambitious book. The book bombards the reader with so much sex, sex, and more sex that the reader is forced to come to grips with this as a way of life, even if the reader doesn’t share the desire for cock cheese or coprophagia. Yet it’s a profound mistake to dismiss a book, as one vanilla urchin did, because you lack the courage to push beyond your comfort zone. Delany’s opus may seem to be a repetitive depiction of a couple fucking, but the patient and careful reader will discover a surprisingly moving book about growing older, how underground subcultures are increasingly ignored, and how history is not so much about one person’s overnight success but sum of brave gestures from strangers. (Bat Segundo interview with Delany, May 2012)

A.M. Homes, May We Be Forgiven: Years ago, when American novels were still permitted to capture everything, books like The Adventures of Augie March were conversational centerpieces that captured the imagination of popular and literary audiences alike. Yet in recent years, literature has shifted to the twee and superficial. We apparently need our books to bray loud with sheepish sentiments, such as this dreadful sample from Dave Eggers’s A Hologram from the King:

His decisions had been short sighted.

The decisions of his peers had been short sighted.

These decisions had been foolish and expedient.

When prose this unintentionally hilarious is allowed to rise to the top, it’s enough to make you wonder how the deck is stacked against the voices that really count. Especially when the rare book like A.M. Homes’s May We Be Forgiven comes along, demanding something more than unpardonable pablum. Homes was the truly ambitious American novelist this year. Her sixth novel dared to map the surrealistic nature of life with great humor and inventiveness: two paramount qualities missing from that doddering dope in San Francisco. Here’s what happens in the first few pages of the book: kitchen seduction, a bizarre murder, divorce, a man thrust into the role of surrogate parent. You read this book asking yourself how Homes can ever find a narrative trajectory for Harry Silver, whose scholarly devotion to Nixon suggests a Godwin-friendly update to Don DeLillo’s Jack Gladney. Somehow, despite Internet sex and bar mitzvahs in South Africa, May We Be Forgiven becomes a hopeful book about accepting the family and friends who come to you. It features amusing cameos from real-life figures like Lynne Tillman, Julie Nixon Eisenhower, and David Remnick. And it acknowledges its debt to Bellow with the wryly named firm of Herzog, Henderson, and March. (Bat Segundo interview with Homes, September 2012)

Hari Kunzru, Gods Without Men: With all due respect to Douglas Coupland, the Translit label is dodgier than New Adult. Coupland was right to celebrate Kunzru’s smart and spiritual novel for its ability to span history and geography “without changing psychic place.” But when you’re using Hollywood terms like “tentpole” to reinforce your label, there’s a good chance you’re blowing a bit of smoke up the Gray Lady’s ass to get a little attention. Still, none of this should steer readers away from this fine novel. Gods Without Men contains everything from a hilariously inept rock star to a predatory linguist whose efforts to collect Native American stories belie a sad privilege. How much of the world’s difficulties can be chalked up to abandoning one’s wonder and humility at a cross-cultural nexus point? Kunzru, to his credit, avoids a schematic answer to this question. We see how secular faith turns disastrous and back again, with an Ashtar Galactic Command acolyte transformed into a victim. Jaz and Lisa Matharu, a couple recovering from the 2008 recession and trying to contend with their missing son, form a triangulation point of sorts. It’s the reader’s duty to discover more blanks. (Two part Bat Segundo interview with Kunzru, March 2012: Part One, Part Two)

Hari Kunzru, Gods Without Men: With all due respect to Douglas Coupland, the Translit label is dodgier than New Adult. Coupland was right to celebrate Kunzru’s smart and spiritual novel for its ability to span history and geography “without changing psychic place.” But when you’re using Hollywood terms like “tentpole” to reinforce your label, there’s a good chance you’re blowing a bit of smoke up the Gray Lady’s ass to get a little attention. Still, none of this should steer readers away from this fine novel. Gods Without Men contains everything from a hilariously inept rock star to a predatory linguist whose efforts to collect Native American stories belie a sad privilege. How much of the world’s difficulties can be chalked up to abandoning one’s wonder and humility at a cross-cultural nexus point? Kunzru, to his credit, avoids a schematic answer to this question. We see how secular faith turns disastrous and back again, with an Ashtar Galactic Command acolyte transformed into a victim. Jaz and Lisa Matharu, a couple recovering from the 2008 recession and trying to contend with their missing son, form a triangulation point of sorts. It’s the reader’s duty to discover more blanks. (Two part Bat Segundo interview with Kunzru, March 2012: Part One, Part Two)

Laura Lippman, And When She Was Good: “If you have to stop to consider the lie,” says protagonist Heloise Lewis, “the opportunity has passed.” With eleven Tess Mongaghan novels and seven stand-alones, it’s become all too easy to take Laura Lippman’s work for granted. But Lippman’s latest novel, which is also something of a sly riff on Philip Roth’s 1967 novel, is one of her best: an astutely observed tale of a deeply complicated and endlessly fascinating woman. By day, Heloise Lewis is a single mother who reads classic literature. But she also runs a high-end escort service. The book’s alternating chapters headlined with dates reveal Heloise in the present day and Helen, the struggling young woman who transforms into Heloise, is captured in the past. But it becomes swiftly apparent that the present informs the past, rather than the other way around. Heloise believes she is in control. She’s thought out her business and her demeanor, but we come to wonder how she allows so many people, ranging from the imprisoned Val to a prostitute who works for her, to take advantage of her. This is a very thoughtful book about the follies of trying to know or outthink everything, which applies to all quarters. Lippman also gets bonus points for including one of the most creative paper shredding contraptions I’ve ever seen in fiction. (Bat Segundo interview with Lippman, August 2012)

Laura Lippman, And When She Was Good: “If you have to stop to consider the lie,” says protagonist Heloise Lewis, “the opportunity has passed.” With eleven Tess Mongaghan novels and seven stand-alones, it’s become all too easy to take Laura Lippman’s work for granted. But Lippman’s latest novel, which is also something of a sly riff on Philip Roth’s 1967 novel, is one of her best: an astutely observed tale of a deeply complicated and endlessly fascinating woman. By day, Heloise Lewis is a single mother who reads classic literature. But she also runs a high-end escort service. The book’s alternating chapters headlined with dates reveal Heloise in the present day and Helen, the struggling young woman who transforms into Heloise, is captured in the past. But it becomes swiftly apparent that the present informs the past, rather than the other way around. Heloise believes she is in control. She’s thought out her business and her demeanor, but we come to wonder how she allows so many people, ranging from the imprisoned Val to a prostitute who works for her, to take advantage of her. This is a very thoughtful book about the follies of trying to know or outthink everything, which applies to all quarters. Lippman also gets bonus points for including one of the most creative paper shredding contraptions I’ve ever seen in fiction. (Bat Segundo interview with Lippman, August 2012)

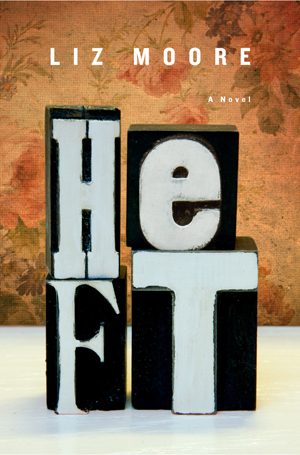

Liz Moore, Heft: Last year, a research team at the University of Buffalo conducted a study with 140 undergraduates which suggested that fiction causes readers to feel more empathy towards others. Empathy seems to be getting a bad rap in fiction these days, especially among some enfants terribles who seem to believe that novels are more about slick heartless style rather than human existence. On the flip side, you have the gushing New Sincerity movement, in which people are interested in mashing irony and sincerity into a roseate sandwich. These strange tonal prohibitions on what one should or should not do in a novel drive me up the wall. If you’re spending so much of your time second-guessing how you should write, then how can ever achieve any original viewpoint? So it was with great joy and relief to discover Liz Moore’s wonderfully endearing novel early in the year about Arthur Opp, a 550 pound man who has not left his Greenwood Heights home in more than a decade and a teenager from a troubled upbringing. Heft proves, first and foremost, that caring about people has little to do with falling along an irony/sincerity axis. Moore told Jennifer Weiner that writing about Arthur let her “write sentences I would have felt self-conscious about writing.” And it (Bat Segundo interview with Moore, February 2012)

Liz Moore, Heft: Last year, a research team at the University of Buffalo conducted a study with 140 undergraduates which suggested that fiction causes readers to feel more empathy towards others. Empathy seems to be getting a bad rap in fiction these days, especially among some enfants terribles who seem to believe that novels are more about slick heartless style rather than human existence. On the flip side, you have the gushing New Sincerity movement, in which people are interested in mashing irony and sincerity into a roseate sandwich. These strange tonal prohibitions on what one should or should not do in a novel drive me up the wall. If you’re spending so much of your time second-guessing how you should write, then how can ever achieve any original viewpoint? So it was with great joy and relief to discover Liz Moore’s wonderfully endearing novel early in the year about Arthur Opp, a 550 pound man who has not left his Greenwood Heights home in more than a decade and a teenager from a troubled upbringing. Heft proves, first and foremost, that caring about people has little to do with falling along an irony/sincerity axis. Moore told Jennifer Weiner that writing about Arthur let her “write sentences I would have felt self-conscious about writing.” And it (Bat Segundo interview with Moore, February 2012)

Jess Walter, Beautiful Ruins: “But aren’t all great quests folly? El Dorado and the Fountain of Youth and the search for intelligent life in the cosmos –- we know what’s out there. It’s what isn’t that truly compels us.” As America slogs its way out of a recession, it was a great relief to read a book hitting romance from so many angles. Walter understands that true quests aren’t necessarily measured in time and distance, but in hope. Beyond Walter’s funny descriptive details (“table-leg sideburns,” “the big lamb-shank hand of Pelle”) which mimic the larger-than-life hyphenated banter found in a Hollywood script, Walter is so good on the page that he allows a film producer to seduce us through a cliche-ridden memoir containing such dimebag philosophy as “We want what we want.” (Bat Segundo interview with Walter, July 2012)

Jess Walter, Beautiful Ruins: “But aren’t all great quests folly? El Dorado and the Fountain of Youth and the search for intelligent life in the cosmos –- we know what’s out there. It’s what isn’t that truly compels us.” As America slogs its way out of a recession, it was a great relief to read a book hitting romance from so many angles. Walter understands that true quests aren’t necessarily measured in time and distance, but in hope. Beyond Walter’s funny descriptive details (“table-leg sideburns,” “the big lamb-shank hand of Pelle”) which mimic the larger-than-life hyphenated banter found in a Hollywood script, Walter is so good on the page that he allows a film producer to seduce us through a cliche-ridden memoir containing such dimebag philosophy as “We want what we want.” (Bat Segundo interview with Walter, July 2012)

Chris Ware, Building Stories: The box contains no instructions. The pieces range in size and can be read in any order. The characters have no names. The illustrations are beautiful. The form is paper, but that doesn’t stop Ware from reflecting on where digital technology is taking us, both in stark and in speculative terms. There is pain and pleasure and cycles and secret history. There is loneliness and togetherness. My partner and I spent an entire Saturday sifting through this box. We felt compelled to talk more about life. As the pieces were carefully unpacked, we began to treat the comics with an unanticipated reverence, even though there was no way we would never fully know the people that Ware had rendered. Building Stories is the rare prayer that grabs the lapels of the secular. It is your duty to give a damn. It is your duty to feel. (Bat Segundo interview with Ware, November 2012)

Honorable Mention:

Jami Attenberg, The Middlesteins

Brian Evenson, Immobility

Richard Ford, Canada

Nick Harkaway, Angelmaker

Katie Kitamura, Gone to the Forest

J. Robert Lennon, Familiar

Stewart O’Nan, The Odds

Nick Tosches, Me and the Devil

Karolina Waclawiak, How to Get Into the Twin Palms

Adam Wilson, Flatscreen