There were about thirty-five people packed within the dark vermilion confines of an East Village pastime on a Thursday night. They were there for Behind the Book, an outfit dedicated to the noble practice of turning young people into readers. And while I could spot a good share who were there for the opening act, there were some swinging back hard drinks to believe a little harder in a literary clime that no longer existed. But the crowd was solemn, quiet. They cleaved to the blue glow of smartphones between acts. Because that is what introverts do when you put them in a bar.

“Good evening. Is this on?”

This uncertainty set an apropos tone for a literary evening. Jürgen Fauth, sporting beard and blue shirt and a beer bottle he clutched in his left hand, was the first at the KGB Bar. He had come in from Germany with the residue of jet lag, but he was excited to be there. He was the only reader among the three to mention his fellow readers. The big man that Fauth name-checked in his oral chronicle of cross-country driving was Mark Leyner, the third man to read that night, spending much of the night sitting without a smile not far from the low-key lectern but facing the crowd. In younger days, Fauth was careful to pack Gravity’s Rainbow, Brautigan, and a copy of On the Road when he hit the road. He confessed to pilfering the Gideon Bible from every motel he happened to stay in.

Fauth stood before the crowd to read from Kino, his latest novel. He was straight to the point in his comic take on inflation in 1924 Germany. And when the passage shifted to a mode of celebration, Fauth stopped, saying, “Oh wait, let’s drop this,” heading back to his monetary tale of woe.

Fauth’s excerpt snaked its way toward the great Expressionist film director, Fritz Lang, who Fauth’s protagonist called a “miserable son of a bitch” and “an insufferable asshole.” Did Lang really assign numbers to gestures for his actors? I don’t know, but the notion was a darkly comic one, leading quite naturally to a point in Fauth’s story where cocaine fueled a coterie of twenty-five actors who were operating an absurd monster.

If this was the stuff that Kino was about, then perhaps it was worth a read. As all this was happening, there was screaming of some not easily identifiable form downstairs. And a literary enthusiast closed the door. Perhaps this unknown soul was in need of the very faith Fauth was dramatizing. It wouldn’t be the last sound of the evening.

“Can we turn down the mike please?”

There was introductory talk of someone having the pleasure of working with Francine Prose in the Bronx, and for some reason I thought of the affluent socialites in My Man Godfrey scavenging William Powell. This isn’t a snipe at the nobles, much less Behind the Book. If it takes a figure as uptight as Francine Prose to get kids believing that having imaginary friends isn’t necessarily a crazy idea, then I’m all for throwing the persnickety into the creative conflagration.

Tom Perrotta wasn’t uptight, but he wasn’t as lively as I had hoped. The gathered crowd looked up at Perrotta like he was an avuncular man at a campfire, the glow of the light lending authority. But his approach, which involved reading five to seven words at a time with a pause of import, quickly wore thin. I have seen this tic used at too many readings. The problem may have been Perrotta’s novel, The Leftovers. Apocalyptic stories require oomph. Brian Francis Slattery understands this, which is why he often reads his work with a band.

Perrotta had no band. A blue-shirted bartender paced up and down as he read, shaking his head from side to side and pining for the next break, the next influx of singles. And who can blame him? Perrotta droned on. The bartender shifted some stray ice cubes back inside the curved perimeter of a metallic bin. Perrotta read. And read. But then he read something that might have accounted for his approach:

The more conspicuous you were, the easier it was for people to take you at face value — they just wrote you off as a couple of harmless dirtbags and left it at that.

I wouldn’t call Perrotta a harmless dirtbag. I would call him a harmless reader. Maybe he was having a bad day. Who knows? In his defense, his tale got a little better when he mentioned bullseyes appended to his characters’s foreheads. And this lifted my spirits, and it got the crowd going a bit. But his reading didn’t need to be this long.

Now that I’ve seen Mark Leyner read, I think I’ve finally figured him out. He’s the Gallagher of literature. For him, language is a mere prop rather than the stuff of being alive. He believes that offering the acronym BFV and presenting its components (“Best fisting video”) is enough for a joke to take. He believes perfunctory mentions are funny, but he isn’t willing to confront. (Case in point: From The Sugar Frosted Nutsack: “But you can’t find good shawarma in this fuckin’ town now that it’s full of Jews and Freemasons…I’m serious!”)

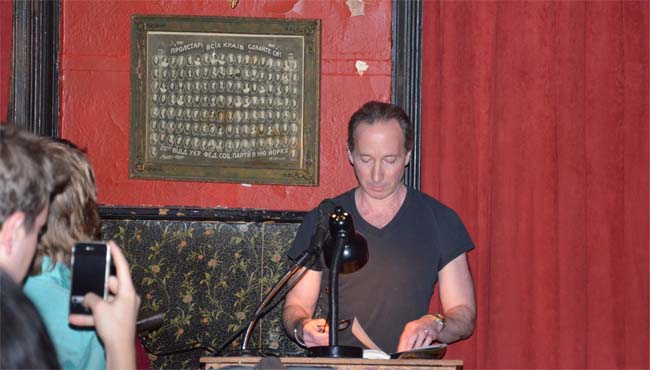

Here is what I can tell you about Mark Leyner from watching him on Thursday night: He reads in a young voice spoiled old that is somewhere between Jerry Seinfeld circa 1987 and a used car salesman. He has this minor uptalk. He is a 56-year-old man who really wishes he were 26, and he writes prose with the depth and maturity of a 26-year-old writer, and he even dresses this way: black tee to show off his long hours at a gym. For a reading? You’re 56. A far cry from the slick suit he once donned on Charlie Rose way back when. Leyner was fond of offering sad flourishes with his right hand that resembled a fading rapper trying to punctuate the latest lingo. But it’s more than this. Because Leyner, pushing 60, actually read the following passage before a crowd:

XOXO finds it amusing to shit on the integrity of the epic, to leave it in a state of suspended animation, a state of complete unfulfillment and nongratification, a form of eternal Tie and Tease. He wants to leave The Sugar Frosted Nutsack 2: Creme de la Sack with an epic case of blue balls. It’s XOXO‘s ultimate mind-fuck.

This is among the shoddy material that Lev Grossman recently identified as “a powerful concentrate of Ulysses.” Right. And Grossman is our contemporary answer to Saul Bellow.

What Grossman and Leyner’s boosters cannot comprehend is that Leyner has not grown at all in the past few decades. Amazingly, David Foster Wallace’s criticism (PDF) still remains applicable:

The book does this by (1) flattering the reader with appeals to his erudite postmodern weltschmerz, and (2) relentlessly reminding the reader that the author is smart and funny.

It was largely men who laughed. Some women did too. But I observed four women walk out during Leyner’s reading. And it wasn’t just to use the bathroom. They bolted. I suspect another woman might have walked out if a kindly gentleman had not encouraged her to stay by buying her a drink. Good guy. But Wallace’s second point, in particular, was there in Leyner’s delivery on Thursday night. When the audience’s attention flagged during the third part, he even resorted to growling a few choice words.

But the man’s biggest laugh came from a Billy Joel joke.

A true comic writer — a Sam Lipsyte, a Paul Murray, a Gary Shteyngart, a Sara Benincasa — would secure the grandest chuckle without using pop culture as a crutch. A true writer would share some tangible experience of what it is to be human or would have a bit of fun, as Fauth and even Perrotta did. But for the author of the bestselling Why Do Men Have Nipples?, the nutsack was adequate enough.