[This is the third in a series of posts relating to the 2009 New York Film Festival.]

At the Life During Wartime press conference, I noticed that director of photography Ed Lachman was a bit grumpy about differences between shooting on film and shooting digital. Life During Wartime had been shot, like Steven Soderbergh’s The Informant!, on the RED digital system. Now Soderbergh’s film looked a bit soft and strained to my eye. Lachman, on the other hand, had managed to beef up much of Life During Wartime using color correction. But I was really curious about how Lachman got these results. Plus, Lachman was wearing a pretty snazzy and stylin’ hat.

At the Life During Wartime press conference, I noticed that director of photography Ed Lachman was a bit grumpy about differences between shooting on film and shooting digital. Life During Wartime had been shot, like Steven Soderbergh’s The Informant!, on the RED digital system. Now Soderbergh’s film looked a bit soft and strained to my eye. Lachman, on the other hand, had managed to beef up much of Life During Wartime using color correction. But I was really curious about how Lachman got these results. Plus, Lachman was wearing a pretty snazzy and stylin’ hat.

So I tracked him down, figuring that two guys sharing the same first name might just get along, and recorded an impromptu interview, which you can listen to at the end of the post. Many thanks to Mr. Lachman for being very gracious in talking with me just as he was heading out the door. My apologies to any cinematography die-hards for being a tad rusty.

Here’s the transcript.

Correspondent: I wanted to ask you about the use of the RED digital system for this versus what you’ve done in terms of film. You alluded during the press conference to having some struggle trying to get the color right. Presumably, a lot of color correction in post. I’m curious to what degree you relied on preexisting locations, whether planning has completely shifted thanks to the RED digital system, and whether you have any possible regrets over this possibly inevitability of where film is headed.

Lachman: Well, I think there’s a place for the digital world and a place for film, and also the merge between the film and digital world. It’s just that my eye and feeling is toward film. Because that’s what I grew up with. It’s not to negate that certain stories can’t be told digitally. But I think it’s an erroneous argument to worry that the digital world should be film. Because the color space is different and the exposure latitude is greatly lessened. Now with a lot of time and money, you can get the digital world closer to film. But for me, it’s still not there yet. And the question they always bring up is that it’s a cost factor. Because it’s like $1,000 a roll for processing of 35mm. But I’ve seen the trend back towards film. Even if you shoot in Super 16 or three-perf 35mm or two-perf 35mm, and then go through a digital intermediate, to me, that’s like the best of both worlds. Where you’re originating on film because of the exposure and the color latitude of the film and also because, in the digital world, at least with the RED, you’re not actually seeing what you’re getting on the set. And the cameraman has to rely on what his eye and, when we use film, our light meter and our lenses. And with the RED, you have to estimate what it’s going to look like. Because you’re not actually seeing at what they say 4K, but is actually 3.2K at the output. Because monitors aren’t at 4K or 3K.

Correspondent: I’m curious. Where do you think digital filmmaking needs to go in order to be acceptable for you? Is it a matter of anticipating how you second-guess how it’s going to look? Once you factor in the potential color correction, the potential fixing in post, and the like? I mean, how does the eye adjust with such developments?

Lachman: Once the digital world can equate the exposure latitude with film, which I would say is close to ten or twelve stops. And for me, in the digital world, it’s about half of that. And then also, you know, there’s something to say about why an image looks the way it does. Being analog versus digital. And there’s a random access to the analog image on film in which actually it’s like an etching. The film is being created by light because of the action — not to get too technical, but the silver in the film is being etched away by the film. And then you’re projecting with light through a piece of film when you see a film. And digital, you’re on one plane. So your shadows and your highlights are on this one plane. And it has a different feeling. And I’m saying there are certain stories that I think can be told very well digitally. And I used the digital world as best I could in Life During Wartime, and I’m happy with the results. But I had to do a lot of post work to bring out things I wanted to feel and see in the digital format that in film I would have had.

Correspondent: What was the worst case scenario in terms of color correction? Did you have a situation in which you lit the heck out of a scene and you got it absolutely how your eye wanted it and it didn’t turn out that way when you looked at it?

Lachman: It’s not so much in lit situations. I can control that. It’s more in unlit situations when you’re outdoors and when you have a strong contrast of over ten or twelve stops. Between shadow, detail, and highlights. And there’s a scene — it’s a fantasy sequence — when you pan around a lake and you see the boy standing there. And you cut back and forth. I had to do that in a number of different passes to bring out the shadow detail, to bring out the highlight. And then I did it for the color space. And that’s not something I would have had to do in film.

Correspondent: How many passes did you do for that shot?

Lachman: Well, each take, I probably did about six passes.

Correspondent: Did you have to record a certain amount of information per pass and mix it all together?

Lachman: You do a matte actually. So you matte out. Let’s say you go for the shadow detail. Matte out the other part. Then I went for the highlights. So I just did different passes. And they can put it together. But that’s very time-consuming.

Correspondent: Well, I’m curious. For a practical situation. For example, the night time parking lot scene. There you have a situation in which you have very little light. And you have to get this image of a woman walking in her nightgown across a parking lot. And so with a situation like that, was that pretty much all color correction? What did you do in terms of lighting the scene to ensure that there was some kind of information there to work with?

Lachman: Well, I’m glad you thought there wasn’t much light. And there wasn’t a lot. But I had to light it on a crane. A 12K on a crane. An 18K. And then a bounce. So I lit it the way I would have done it on film. Another aspect of the digital world that nobody tells you about is: Film right now, you can shoot at ASA 500, push it a stop, 1000, and get incredible results. The digital format, it’s about 200 to get an image that’s acceptable, that isn’t noisy and you have problems later with. So you’re losing a stop to a stop and a half to almost two stops. So then you’re in a position that you have to use more light. So then why are you gaining something by shooting in the digital world over film? Now the digital format loves low light. And I think that shooting at night scenes digitally is wonderful. Because you have lower contrast ratio. But in high contrast situations, where there’s a lot of light, the digital world, you get artifacts. You get highlights burning out. You don’t get as much information as you do with film.

Correspondent: What’s the ideal lighting for a digital situation? Presumably, how would Kino Flos work in relation to film versus digital?

Lachman: Well, you have to keep it within a certain range. Let’s say a 3:1 ratio. Where in film, you might go with a 6:1 ratio. So you just have to be a lot more careful. It’s almost for me like shooting with reversal film. Positive film, what we used to shoot. Now we shoot primarily negative. Well, we do shoot negative film. But when we used to shoot in positive film. Let’s say with documentaries or whatever. You had to be much more careful about the exposure latitude you shot with.

Correspondent: Since you’re dealing with such a limited spectrum, how have you adjusted, say, getting a spot meter reading or a light meter reading?

Lachman: Even though it’s a digital world and people laugh at me, I use my spot meter once I’ve evaluated what the ASA of the digital medium is. And I like to rate it around 200. I then just balance it with my spot meter the way I do with film.

Correspondent: Have you managed to get it so that you pretty much get an ASA 200 reading that more or less reflects the final results without artifacts? Or are you still having problems?

Lachman: No, I rate it at 200 and then do an exposure latitude of a stop and a half on the highlights and the shadow detail. That’s what you’re looking at in the film. When you see just the detail in Michael Kenneth Williams’s face, he’s African-American. And it’s so wonderful. You just read the detail. That’s because I made sure about what my ratio was between the highlight and the shadow. You know, I think part of the mystique of the whole digital world is the idea that for directors, it’s a liberating thing. If they see an image, they can shoot. But it’s a lot more than seeing the image that you have. It’s also about balance in the scene and it’s about creating the continuity of the image, so to speak. So it’s not enough to say, “Oh, I have an image we can shoot.” What happens when you go into the close-up? What happens when you start at one point of the day and you have sunlight and at the end of the day you’re in shadow or clouds? So it’s about balancing to make a scene look like it’s a continuation of the same time period, which many times you’re not allowed to do.

Correspondent: This leads me to actually ask you about depth of field and focus lengths. Obviously, if you don’t have as much of a spectrum, you’re going to have limits in terms of how far you can use the Z-axis. And I’m curious about how your photography has changed in light of the focus problem.

Lachman: I don’t worry about that. People say you have more depth of focus digitally than you do with film. That doesn’t worry me. If I use a longer lens. If I want to knock the background out.

Interview with Ed Lachman (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced

Listen: Play in new window | Download

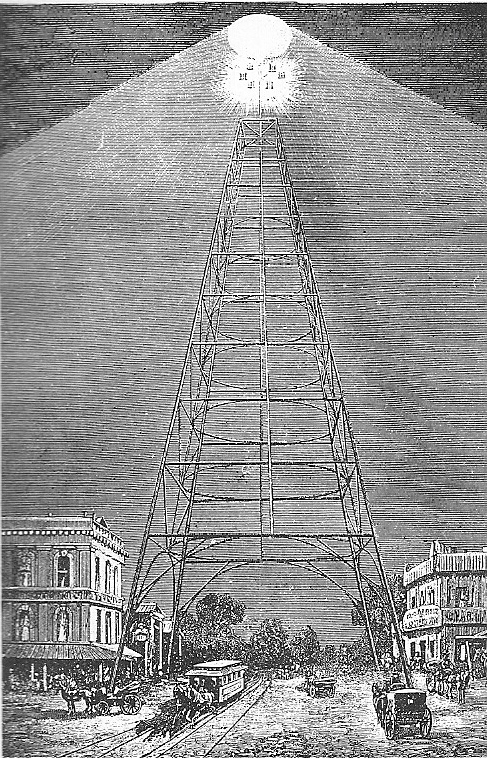

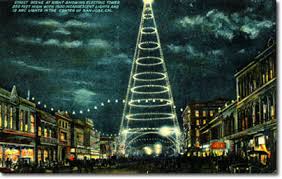

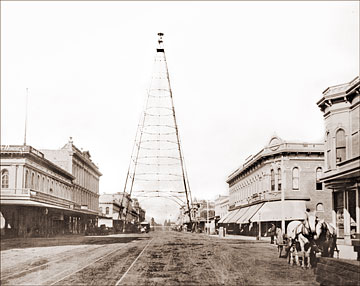

The tower never produced the searing glow that Owen longed for, but it served as a symbol of hope and progress to the people of San Jose. Electricity had only just arrived and the frame of the tower was juiced up by sizzling refulgence. Birds often smacked into its tempting bones, lured by the light, and it is said that policemen cadged a bit of pin money by hawking fallen duck corpses at local establishments. Drunkards often attempted to scale it. Moreover, San Jose had beaten Paris to the punch. Alexandre Gustave Eiffel pilfered the plans and, eight years after Owen’s gigantic tower was raised, Eiffel constructed his own version. This French treachery caused San Jose to sue Paris in 1989 for the century-long appropriation. In the trial, the architect Pierre Prodis claimed that the Eiffel Tower was merely a “trace job” of Owen’s vision. Paris triumphed in the court, but not without the famous engineer’s legacy sullied.

The tower never produced the searing glow that Owen longed for, but it served as a symbol of hope and progress to the people of San Jose. Electricity had only just arrived and the frame of the tower was juiced up by sizzling refulgence. Birds often smacked into its tempting bones, lured by the light, and it is said that policemen cadged a bit of pin money by hawking fallen duck corpses at local establishments. Drunkards often attempted to scale it. Moreover, San Jose had beaten Paris to the punch. Alexandre Gustave Eiffel pilfered the plans and, eight years after Owen’s gigantic tower was raised, Eiffel constructed his own version. This French treachery caused San Jose to sue Paris in 1989 for the century-long appropriation. In the trial, the architect Pierre Prodis claimed that the Eiffel Tower was merely a “trace job” of Owen’s vision. Paris triumphed in the court, but not without the famous engineer’s legacy sullied. I learned of the tower when I was five, attracted to the pointillist rings glowing on photos and postcards. I was smitten by the great circular aura shooting into the onyx skyscape from the six carbon arc lamps planted at the tower’s peak. And when my parents took me to Kelly Park, I became overcome with tumultuous wonder when my little eyes snagged onto a replica of the tower built in History Park. The replica was only 115 feet tall, recently constructed, and I remember asking the tour guide why it was so small. I had somehow remembered the height of the original, plucking it from some stray placard that most tourists ignored. What was the point of reproducing a tower if you couldn’t put it in the right place or match the previous height? The tour guide, sifting through his mental arsenal for general historical information to answer my question, told me how the original tower fell. Gale force winds had ravaged the tower on December 3, 1915. It was the deadliest part of a vicious storm. The center of the massive metal structure wended and wobbled and, just before noon, pipe and metal poured onto San Jose’s streets. I closed my eyes and began to imagine the beautiful tower destroyed, and I remember silently crying, knowing that the tower’s end was needlessly permanent. I don’t remember the tour guide’s exact words, but there was a peremptory tone in his voice, a suggestion that it was mad folly to build another tower and cause harm to future San Jose residents. San Jose still suffered from wintry winds every now and then. And there was still the possibility, especially given the freak 1976 snowstorm from a few years before, that the tower could do more damage.

I learned of the tower when I was five, attracted to the pointillist rings glowing on photos and postcards. I was smitten by the great circular aura shooting into the onyx skyscape from the six carbon arc lamps planted at the tower’s peak. And when my parents took me to Kelly Park, I became overcome with tumultuous wonder when my little eyes snagged onto a replica of the tower built in History Park. The replica was only 115 feet tall, recently constructed, and I remember asking the tour guide why it was so small. I had somehow remembered the height of the original, plucking it from some stray placard that most tourists ignored. What was the point of reproducing a tower if you couldn’t put it in the right place or match the previous height? The tour guide, sifting through his mental arsenal for general historical information to answer my question, told me how the original tower fell. Gale force winds had ravaged the tower on December 3, 1915. It was the deadliest part of a vicious storm. The center of the massive metal structure wended and wobbled and, just before noon, pipe and metal poured onto San Jose’s streets. I closed my eyes and began to imagine the beautiful tower destroyed, and I remember silently crying, knowing that the tower’s end was needlessly permanent. I don’t remember the tour guide’s exact words, but there was a peremptory tone in his voice, a suggestion that it was mad folly to build another tower and cause harm to future San Jose residents. San Jose still suffered from wintry winds every now and then. And there was still the possibility, especially given the freak 1976 snowstorm from a few years before, that the tower could do more damage. I didn’t remember the snowstorm because I was an infant at the time. But like the Electric Light Tower, it had been captured in family photographs assembled in blue-covered albums identified sequentially by numbered stickers, so that I could trace the precise moment that the memories of my life aligned with the photographs. I had no memory of the snowstorm, but I had lived through it. I was forming memories of the electrical tower, visions that made it more real than any representation, yet I hadn’t been fortunate enough to be alive during the time of its existence. (I would have similar feelings for the Victorian version of the Cliff House constructed by Adolph Sutro in 1896, a magnificent multiroom palace with sharp gables famously captured in photographs during a thunderstorm. It burned to the ground on September 7, 1907 — another architectural tragedy, another great structure destroyed on a whim.)

I didn’t remember the snowstorm because I was an infant at the time. But like the Electric Light Tower, it had been captured in family photographs assembled in blue-covered albums identified sequentially by numbered stickers, so that I could trace the precise moment that the memories of my life aligned with the photographs. I had no memory of the snowstorm, but I had lived through it. I was forming memories of the electrical tower, visions that made it more real than any representation, yet I hadn’t been fortunate enough to be alive during the time of its existence. (I would have similar feelings for the Victorian version of the Cliff House constructed by Adolph Sutro in 1896, a magnificent multiroom palace with sharp gables famously captured in photographs during a thunderstorm. It burned to the ground on September 7, 1907 — another architectural tragedy, another great structure destroyed on a whim.) There hasn’t been a year when I haven’t thought about the tower. Yet I wonder how long I can keep its vision alive in my heart and mind. Nobody seems to remember it or care about it outside San Jose. Nobody wants to honor the tower that once attracted international attention. I can’t talk about the Electric Light Tower with anyone, especially on the East Coast. It is, like many funny ideas in the history books, an eccentric and possibly nonsensical idea. But for a decent stretch in history, it held one city together.

There hasn’t been a year when I haven’t thought about the tower. Yet I wonder how long I can keep its vision alive in my heart and mind. Nobody seems to remember it or care about it outside San Jose. Nobody wants to honor the tower that once attracted international attention. I can’t talk about the Electric Light Tower with anyone, especially on the East Coast. It is, like many funny ideas in the history books, an eccentric and possibly nonsensical idea. But for a decent stretch in history, it held one city together.

At the Life During Wartime press conference, I noticed that director of photography Ed Lachman was a bit grumpy about differences between shooting on film and shooting digital. Life During Wartime had been shot, like Steven Soderbergh’s The Informant!, on the RED digital system. Now Soderbergh’s film looked a bit soft and strained to my eye. Lachman, on the other hand, had managed to beef up much of Life During Wartime using color correction. But I was really curious about how Lachman got these results. Plus, Lachman was wearing a pretty snazzy and stylin’ hat.

At the Life During Wartime press conference, I noticed that director of photography Ed Lachman was a bit grumpy about differences between shooting on film and shooting digital. Life During Wartime had been shot, like Steven Soderbergh’s The Informant!, on the RED digital system. Now Soderbergh’s film looked a bit soft and strained to my eye. Lachman, on the other hand, had managed to beef up much of Life During Wartime using color correction. But I was really curious about how Lachman got these results. Plus, Lachman was wearing a pretty snazzy and stylin’ hat.