Jesmyn Ward is most recently the author of Men We Reaped. She previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #463.

Author: Jesmyn Ward

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: Adorable literary babies, the notion of “home” in Mississippi, the Delta Blues, Big K.R.I.T., having a very large extended family, environments that foster great art, Kiese Laymon, why culture demands engagement, Mississippi being dead last in statistics, statistics vs. stories, W.E.B. du Bois’s notion of “double consciousness,” Ward seeing her mother in another context, emotional associations from phrases in languages, “soda” vs. “pop” vs. “cold drank,” Southern language, how the world is prerigged against the poor and the black, having to settle for “live” instead of “live good,” losing early optimism, Ward losing her brother, embracing fatalism and nihilism, C.J. becoming convinced that he would die young, young men who can’t envision a future, finding hope while living in an impoverished world, coming to an understanding of grief, how family and community are elastic and intertwined, finding hope in future generations through memories, Ward’s mother, paying it forward, people who don’t have food in the house, comparisons between Daddy in Salvage the Bones and how Ward wrote about her father in Men We Reaped, how memoir creates additional need which transcends fiction, the difficulties of fictionalizing complicated people, the advantages of creative nonfiction, human contradictions, Ward’s martial arts skills, training with nunchaku and swords, being bullied by racist kids, finding ways of defending yourself when you’re outnumbered, fight or flight, being attacked by a pit bull, suffering from low self-esteem, turning to alcohol to cope, avoiding writing about writing, how to contend with grief when the public playground has been officially designated as a graveyard, the government shutdown, why people care more about baby pandas at the National Zoo than poor people who need food, David Simon, The Wire, journalism vs. storytelling, mediocre white artists who appropriate the best of black culture, shying away from true engagement, white people in the literary world who get a privileged pass, when the Other has to soften itself for white consumption, timid Goodreads reviewers, Mitchell S. Jackson, response to writers of color, “designated” African-American authors, Ward’s difficulty with the telephone, receiving terrible news, and finding the bravery to take in difficult communication.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I want to get into this incident late in the book where you describe being bullied by racist kids. There’s one moment after they crack some really terrible quip about lynching you where you say, “You ain’t going to do nothing.” And these kids, they just dissemble. They just disappear. They have nothing to say after that. And it’s this fascinating moment, particularly when we’re looking at this other incident with this kid Topher, who was verbally pulverizing you. And the teacher’s just standing there not willing to acknowledge the racist language. You write about how the kids, some of whom were your friends, “they never took up for me, for Black people, when I was in the room.” And throughout this book, you don’t let yourself off the hook. I mean, you write about how you were scared to walk through certain neighborhoods. You write about how your little brother, two years younger, had more courage in a certain situation. And so when we’re talking of this notion of self-defense, I have to ask you, Jesmyn, what do you think it was that caused you to not only stand up to these kids, but also do something that either the other black kids in the school couldn’t do? That’s something that was extraordianrily rare, especially because you’re not exactly the most extroverted person in the world.

Ward: Yeah.

Correspondent: So what do you think it was that caused you to really get these kids rightfully off of your back?

Ward: I don’t really know. Especially because, before then and even afterwards, I wasn’t very good at taking up for myself. And I think that part of that was informed by the fact that I had really low self-esteem. Because I feel like the world, and also what I saw in my community, had taught me the wrong things about what it meant to be black and poor and a woman in the South. And so I had awful self-esteem. But I don’t know. There was something about that moment — maybe because they were so overt and there were so many of them. It was a pretty large group. Six, seven boys. And they were so much older than I was. You know, I was really young when that happened. I was in seventh or eighth grade and they were upperclassmen.

Correspondent: So they were much taller too.

Ward: Much taller than I was.

Correspondent: Were they pretty muscular?

Ward: Some of them were. So I think that it was a moment where I was so clearly outnumbered and overpowered that maybe it was partly motivated by instinct, right? Fight or flight. And, for once, my response wasn’t just to leave or passively endure it. It was to actually fight. So I think a lot of it was driven by instinct. So I just came out and said it. “You ain’t going to do nothing to me. It’s not going down like that.”

Correspondent: Why do you think these instincts could only come out during certain moments? I mean, you’ve clearly had a fairly remarkable life of getting out of this situation. But what do you think it was that encouraged those instincts to come out at the right moments? Because of course, they came out at the most damaging moments as well.

Ward: Well, I think maybe the situation was so — you know, I said in that moment that the odds were really against me. I was clearly overpowered. Clearly outnumbered. And then my response was to fight in that moment. But then it also makes me think about when I was attacked by that pit bull, right? Clearly the dog is very much stronger than me. Has more weapons than I have. It would have been very easy for me to come out worse in that situation than I did. But in that moment, I chose to fight. That that was my instinctual response, right? That I fought. In both of those instances. And I think maybe in certain situations like that, that they’re the kind of situations that are so severe that the part of me that had the problem with low self-esteem, right? Of course, it’s the part that overthunk everything and that overprocessed everything. So that here in these moments, there’s no opportunity to think. All I could do was react. So my reaction in those moments was to fight. So maybe that’s why. These are these moments where the part of me that has low self-esteem can’t think about it and can’t process that moment in that way. So then I just react without thinking. And that’s what happens.

Correspondent: There is something interesting in that pit bull incident. There’s a sentence you write where you say, “The long scar in my head feels like a thin plastic cocktail straw, and like all war wounds, it itches.” And in light of how you went through this period of drinking, I’m wondering how long it took for you to make this connection between surviving a war and, with the cocktail straw, turning to drink in this effort to cope, in this effort to deal with the pain and to combat this low self-esteem.

Ward: It took me a long time. You know, I don’t think that I began to realize the way that I was turning to alcohol in order to deal with what I’d been through. Probably I began to realize that while I was at Michigan. While I was in New York, and I was doing the drinking when I said I was buying bottles of rum and basically just drinking them with a little bit of sugar. I didn’t realize it then. And I think that was from 2003, so I was in the throes of it. But it wasn’t until around 2006. Because I began to drink alone. And that’s when it suddenly hit me. Like what I was. Because I would drink alone and then I would become very depressed and very moody. And I would act out. And, see, before whenever I’d done that sort of drinking, I had roommates. I lived with other people. We were out in social situations. So I didn’t really think about it. But there was something about beginning to drink alone that made me suddenly begin to draw those conclusions between what I’d gone through and how I was responding to it and how I was basically self-medicating with alcohol.

Correspondent: It’s fascinating to me that you don’t really get into the beginning of your writing in this memoir. It comes from the exact same impulses as this kind of self-medicating, as this drinking, as this effort to combat terror, fear, low self-esteem. And I’m wondering if it’s even possible for you to even write about the beginning of how writing brought you out of this and allowed you to really manage these emotions more effectively.

Ward: I don’t know why I didn’t really speak more about it in the book or write more about that in the book. I don’t really know. I’ve spoken about it before. I sometimes speak to different universities and I have a speech that I usually give where I actually talk about how I came to writing and how committing to writing, for me, was really a response to the grief that I felt when I lost my brother.

Correspondent: Yes. But it’s compartmentalized, I think. Which I find really interesting.

Ward: I don’t really know why I didn’t address it more in the book. Maybe because I was afraid of shifting that focus maybe away from the young men. And maybe I was nervous about whether or not I could write about it and still sustain maybe the pace and the tension in the narrative, in the memoir. So maybe that’s what was going on.

Correspondent: You had your own problem of [W.E.B. du Bois’s] “double consciousness.”

Ward: Yes! Yes!

Correspondent: That’s interesting. I do want to get into the way that you describe the land of the community, which is extremely fascinating. You point out that the parks, the public parks, are designated as the graveyards in the future. This is going to be the burial site for people who will die in the future. And you openly begin to wonder, “Well, is it possible to stave off this transformation from the life of the playground to the death of the grave?” You write, “The grief we bear along with all the other burdens of our lives, all our other losses, sinks us until we find ourselves in a red, sandy grave.” Yet near the end of the book, when you’re talking about your brother, you are very candid about grief having this limitless life span. So how do you deal with grief when you know that you’re also trying to work away at that buffer that’s going to turn the playground into the graves? I mean, you have to champion life. You have to fend off these forces, both societal and beahvioral, that are trying to deaden all this wonder that surrounds you. So how do you think about grief when you’re very well aware of what’s going to happen?

Ward: Well, I guess that the way that I think about that is that the grief, that’s something that I can’t change. That’s something that is here and that I have to live with everyday. But I think that what I’m attempting to do is to use that grief to really fuel this endeavor, right? The writing of the book. And then also the conversations that I have around the book with different people. So that hopefully in having these conversations, and talking about all these pressures that the grief and the sense of fear and failure that permeates life for so many of the people, that talking about these things is the first step to admitting that there is this problem. Yes, we are all living with this grief. And, yes, we are trying to survive these unbearable pressures. But I’m hoping that if we talk about them, and bring them out into the open and admit that there is a problem involved and exists, then we can begin to be more conscious about our lives, about the actions that we take, how we react to these larger pressures. So that maybe we can begin to change things, right? And to think of concrete ways that we can change things. And I haven’t gotten there yet. Whenever someone asks me “So what can we do?” my only answer so far is that, okay, first we just need to talk about it. We need to enter this conversation that’s happening across the country about race and about young black people dying and about poverty and socioeconomic inequality. If we begin to talk about these things, then maybe we can get to a point where we can come up with concrete workable solutions.

Correspondent: I wonder why small biographies, piecemeal chapters of people who have needlessly lost their lives, almost seems to be the only way to discuss this problem these days. I mean, we don’t want to look at the vast tapestry. We don’t want to all the moving parts. And it gets to be a bit of a headache. If you care at all, you know, it’s going to bog you down. I mean, right now, we’re talking right when the government is going to shut down. And what’s really bizarre about all this is that people are concerned not so much about the fact that these food programs that feed the poor are going to go out, not so much with the Library of Congress closing, not so much with military servicemen, who are living day-to-day, not getting their paychecks. They’re more concerned about these baby pandas at the National Zoo. What do you think we can do to get people on the level of baby pandas? You know what I mean?

Ward: You know, I think that when I wrote the book, and especially when I wrote each chapter about the young men — you know, their lives and their deaths. That’s something that I was trying to affect. Because even if given a chapter, and some of those chapters are short. They’re shorter. If given a chapter, I can make these young men as authentically alive and complicated and unique as I can on the page. Like I’m going to really develop their characters and develop them well enough so that the reader, when encountering these young men — instead of these young men being statistics, they’re actually human beings. They’re actually people. And they can sympathize with them. Then I will have accomplished something. Then suddenly the young man becomes the panda, right? Because we care about them. And so I think that maybe that’s part of it. Because we encounter the numbers all the time, right? And I think it was David Simon that said something like that before. I think he was being interviewed about The Wire, right? And I think the interview was asking him about the difference between the work that he’d done in journalism as a writer and then the work that he was doing as a writer. And he was saying that there’s power in the story. He felt that when he was a journalist that he was trying to communicate the same facts, the facts that he’s trying to communicate in The Wire. But as a journalist, they weren’t causing any change. They weren’t getting through. They weren’t making people care in the way that they care about the pandas. Yet when he worked on The Wire, he was able to reach a wider audience to get that audience to care about the same kind of issues that he was concerned about when he was a journalist. So I think it really is in the power of the story — even if you only have a little bit of space, just using that space as effectively as you can to make these stories real.

Correspondent: Sure. But don’t you think there’s a disconnect between, for example, Trayvon Martin. Everybody is sympathetic to that story.

Ward: Right.

Correspondent: And I marched with a bunch of people here in New York. And it was marvelous. At the time. But ultimately this doesn’t effect policy. It doesn’t actually get things to change. And even with the people who cared about The Wire, inevitably we go into the same corrupt governmental institutions. It seems to me that the only option is to either amp up the number of storytellers to get people to care or there needs to be some drastic change in the way the American mind thinks. And I’m wondering. Do you have any ideas on this?

Ward: I mean, that’s a really difficult question to answer. I think that there should be more storytellers and I think that the stories that are out there, they need more volume. I think that these stories, that’s what we need to be discussing instead of discussing the Kardashians. You know what I’m saying?

Correspondent: I agree.

Ward: That’s the discussion that we need to be having. Those are the stories that we need to be invested in. And the people that we need to be invested in need to not be so concerned with vapid celebrity culture. Because that doesn’t get us anywhere. That doesn’t foster the kind of large-scale change that we need in the American government with policymakers.

(Loops for this program provided by vlalys, djmfl, mingote,danke, and blueeskies.)

The Bat Segundo Show #516: Jesmyn Ward (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced

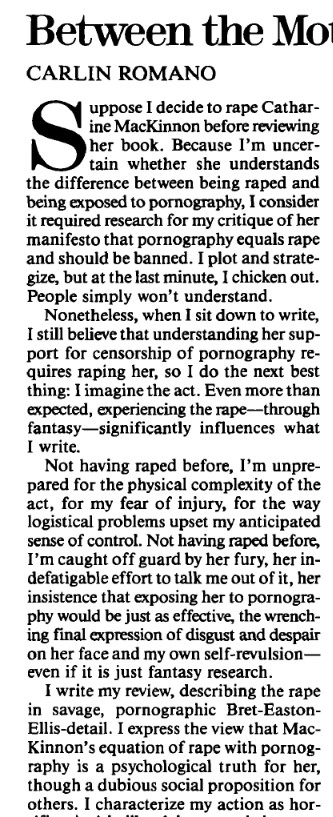

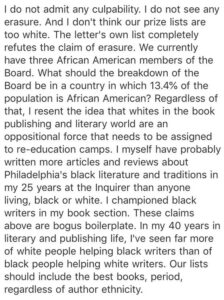

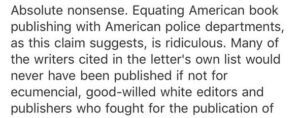

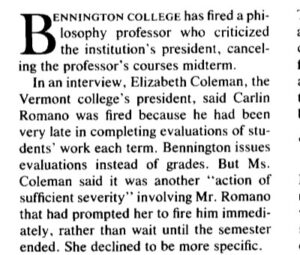

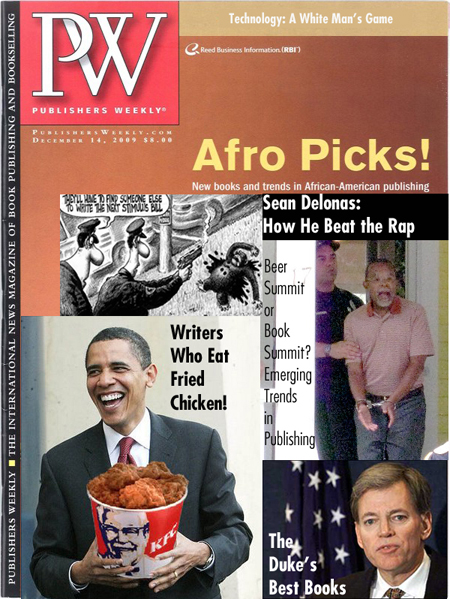

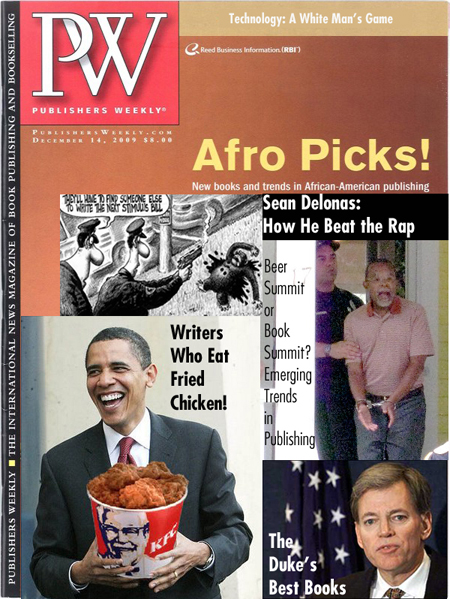

Romano took umbrage with the idea that white gatekeeping “stifles black voices at every level of our industry,” declaring this to be “absolute nonsense.” Never mind that

Romano took umbrage with the idea that white gatekeeping “stifles black voices at every level of our industry,” declaring this to be “absolute nonsense.” Never mind that  Romano got even uglier, claiming that black writers would “never have been published if not for ecumenical, good-willed white editors and publishers who fought for the publication of black writers.” Amber Books? Black Classics Press? Third World Press? Triple Crown Publications? Life Changing Books? Any of the far too few African-American publishers who have stepped up to redress the systemic racism that the largely white-owned publishing industry has failed to remedy? That Romano applies “ecumenical” to his atavistic statement says much about his condescending views of writers of color. Apparently, in his view, any publisher who puts out a worthy novel that happens to be written by an African-American is an act of charity rather than an act of merit. James Baldwin? Toni Morrison? Octavia Butler? Ta-Nehisi Coates? Well, you’re lucky that your ass got through the door because Whitey decided to let one or two of you through the gates. Does Romano’s repugnantly racist sentiment here not reinforce the problems of white gatekeeping and not buttress the need for any and all literary organizations to be more inclusive? As far as Romano was concerned, the fact that countless people of color had to fight to be published — despite the fact that African-American novels have continued to be financially successful (Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren sold one million copies, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple sold five million copies, even Ann Petry’s The Street selling one million copies in 1946, the list goes on) — did not get in the way of his sentiment that black people needed to be fawning and grateful, much in the manner of slaves, to white publishers. Romano doubled down on this racism by writing, “In my 40 years in literary and publishing life, I’ve seen far more of [sic] white people helping black writers than of people black people helping white writers.” In other words, Romano believes that black people should devote their already disadvantaged positions to spending all their time promoting white writers.

Romano got even uglier, claiming that black writers would “never have been published if not for ecumenical, good-willed white editors and publishers who fought for the publication of black writers.” Amber Books? Black Classics Press? Third World Press? Triple Crown Publications? Life Changing Books? Any of the far too few African-American publishers who have stepped up to redress the systemic racism that the largely white-owned publishing industry has failed to remedy? That Romano applies “ecumenical” to his atavistic statement says much about his condescending views of writers of color. Apparently, in his view, any publisher who puts out a worthy novel that happens to be written by an African-American is an act of charity rather than an act of merit. James Baldwin? Toni Morrison? Octavia Butler? Ta-Nehisi Coates? Well, you’re lucky that your ass got through the door because Whitey decided to let one or two of you through the gates. Does Romano’s repugnantly racist sentiment here not reinforce the problems of white gatekeeping and not buttress the need for any and all literary organizations to be more inclusive? As far as Romano was concerned, the fact that countless people of color had to fight to be published — despite the fact that African-American novels have continued to be financially successful (Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren sold one million copies, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple sold five million copies, even Ann Petry’s The Street selling one million copies in 1946, the list goes on) — did not get in the way of his sentiment that black people needed to be fawning and grateful, much in the manner of slaves, to white publishers. Romano doubled down on this racism by writing, “In my 40 years in literary and publishing life, I’ve seen far more of [sic] white people helping black writers than of people black people helping white writers.” In other words, Romano believes that black people should devote their already disadvantaged positions to spending all their time promoting white writers.  In short, Romano articulated in very clear terms just what he wants the system to be. And his deplorable viewpoint here is no different from an antebellum slaveholder. Romano’s despicable vision is this: White editors serving as gatekeepers. Black authors dancing with joy at the honor of having their neutered visions “represented.” Romano’s statement is, in short, a racist screed against literary merit and inclusiveness. That Romano cannot acknowledge any white bias that has prevented great literature from being published, even as he demands that African-American writers jump up and down over concessions that their white counterparts would never have to face, is nothing less than a pompous white xenophobe revealing his true colors.

In short, Romano articulated in very clear terms just what he wants the system to be. And his deplorable viewpoint here is no different from an antebellum slaveholder. Romano’s despicable vision is this: White editors serving as gatekeepers. Black authors dancing with joy at the honor of having their neutered visions “represented.” Romano’s statement is, in short, a racist screed against literary merit and inclusiveness. That Romano cannot acknowledge any white bias that has prevented great literature from being published, even as he demands that African-American writers jump up and down over concessions that their white counterparts would never have to face, is nothing less than a pompous white xenophobe revealing his true colors.

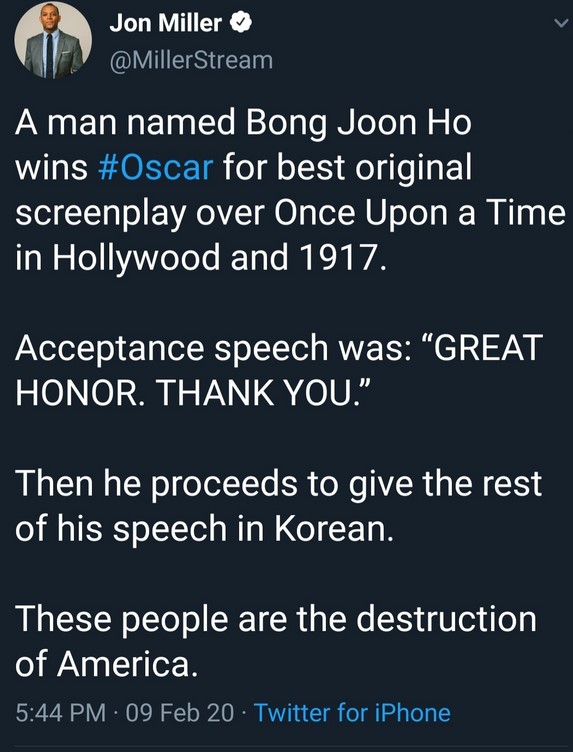

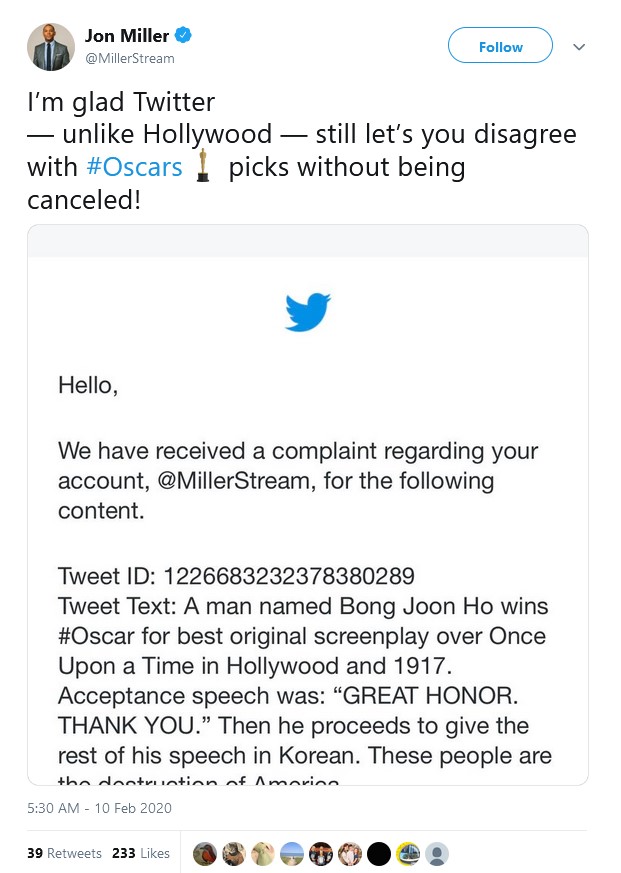

A man with a blue checkmark by the name of Jon Miller, a conservative “White House correspondent for BlazeTV,” tweeted an insulting, cruelly disparaging, and racist message mocking the great filmmaker Bong Joon-ho after he delivered one of his Oscar speeches in Korean. Miller’s disturbingly xenophobic words, which are still published on Twitter as of Monday morning, proceeded to claim that “these people are the destruction of America.” This is language that echoes anti-Semitism in 1930s Germany and

A man with a blue checkmark by the name of Jon Miller, a conservative “White House correspondent for BlazeTV,” tweeted an insulting, cruelly disparaging, and racist message mocking the great filmmaker Bong Joon-ho after he delivered one of his Oscar speeches in Korean. Miller’s disturbingly xenophobic words, which are still published on Twitter as of Monday morning, proceeded to claim that “these people are the destruction of America.” This is language that echoes anti-Semitism in 1930s Germany and

Correspondent: You are careful to write, “Harvard’s importance in eugenics does not imply some nefarious scheme or even a mean-spirited ambiance. Rather, Harvard’s import in this story attests to the scholarly respectability of eugenic ideas at the time.”

Correspondent: You are careful to write, “Harvard’s importance in eugenics does not imply some nefarious scheme or even a mean-spirited ambiance. Rather, Harvard’s import in this story attests to the scholarly respectability of eugenic ideas at the time.”

There are more truths to be found

There are more truths to be found