(This is the nineteenth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: A Bend in the River)

For more than a decade, I have nursed a grandiose grudge towards Wallace Stegner that has less to do with the eco-friendly West Coast bigshot’s literary streetcred and more to do with my own irrepressible ineptitude concerning matters of the boudoir.

For more than a decade, I have nursed a grandiose grudge towards Wallace Stegner that has less to do with the eco-friendly West Coast bigshot’s literary streetcred and more to do with my own irrepressible ineptitude concerning matters of the boudoir.

You see, in my early twenties, long before social networks made it astonishingly effortless to locate a no strings attached entanglement with a few clicks and a seductive missive, I had devised the foolhardy stratagem of attending numerous book clubs, hypothesizing that some law of averages would present me with a reliable method of meeting women. Because I could read thick books fairly quick, discussing the plots and style and themes with some modest wit and intelligence, I developed the odd notion that my quasi-bravura take, seamlessly enmeshed with the views of my peers, would somehow impress the comely damsels within my reach.

The older and more experienced women saw through my ruse, but they tolerated me as some lingering specimen of youthful bravado that reminded them why they were comfortably adult. I remember one happily married woman who was nice enough to give me occasional lifts back from Berkeley and who gently suggested that I lighten the fuck up.

At one point, I was in six book clubs just to keep my options open. While I did wake up in a few literary beds through blind clueless luck and some apparent appeal which I still remain largely in the dark about, it is safe to say that my efforts were mostly unsuccessful, though not as barren as they had been previously.

Now, for reasons probably having to do with Stanford’s proximity, Wallace Stegner was then very popular in the San Francisco Bay Area. And there was one book club I attended in the Outer Sunset where the title being discussed was The Spectator Bird. No problem. I had read it and discussed it before in another book club. On this second effort, there was a chestnut-haired twentysomething who I really liked and wanted to get to know better. The discussion went well and a number of the book club members riffed off what I had to say. Then I made some observation about Joe Allston’s feelings for the Countess being a bit overblown. Because every man had thoughts about other women. Was this really so adulterous?

But I apparently phrased these innocuous thoughts in a way that proved so tasteless that I was asked not to return to the book club.

I later learned that the woman I was trying to ask out for coffee was a family values type saving herself for marriage. There had clearly been no chance.

I took my folly out on Stegner, blaming him for my misfortunes and vowing never to read the man again.

* * *

It was the glint of cash that turned Stegner to fiction writing. During the Great Depression, he had just written his dissertation on the overlooked nineteenth-century naturalist Clarence Edward Dutton. He had come to Utah to teach and was making only $1,800 a year. His wife, Mary, was pregnant. And he saw an advertisement for a novelette contest from Little Brown. Like many of the misleading get rich quick schemes bulging from any issue of Writers Digest, Little Brown promised a $2,500 prize. But Stegner was a stubborn man of will. He sat down and wrote the presciently titled Remembering Laughter, which won the prize and was published in 1937.

There was more teaching and a series of insubstantial novels, until Stegner turned to his own life for material in his 1943 novel, The Big Rock Candy Mountain, and found some success. Still, it was nonfiction’s hard objectivity which guided Stegner during these years like a maritime man following Oléron. While he turned out a steady stream of dependable short stories, he was a late bloomer when it came to the novel’s fatter form. It took the introduction of Joe Allston in 1967’s All the Little Live Things for Stegner to perfect his character model of an older man who enjoyed bitching about the flower children living it up just outside the edge of his damn lawn. Allston was Stegner’s first use of the first person, and the character would pop up again in The Spectator Bird, spawning untold frustration for at least one young punkass a few decades later.

Between Little Live Things and The Spectator Bird, Stegner wrote what is arguably his masterpiece. Lyman Ward, a historian whose legs are amputated, serves this time as Stegner’s first-person coot, and has much to say about the spirit of free thought and free love going down just outside his home (and in a nice twist, Stegner has “the sounds carry up the bare stairs,” suggesting that any vocal intercession from youthful ruffians, which include his son Rodman, are inescapable):

What kind of a loony bin have they got down there in Berkeley, anyway? What kind of a fellow is it that will let his wife support him for two years, living around in those pigpen places, everybody scrambled in together?

Stegner derided “the antihistorical pose of the young,” yet it’s worth pointing out that he did participate in the Vietnam War marches. But when the protests turned violent, he stopped, steeping his crankiness in old school values. History served as the apparent distinction between Stegner and these young muckrakers, and it also served to make Lyman Ward far more than a cantankerous chronicler.

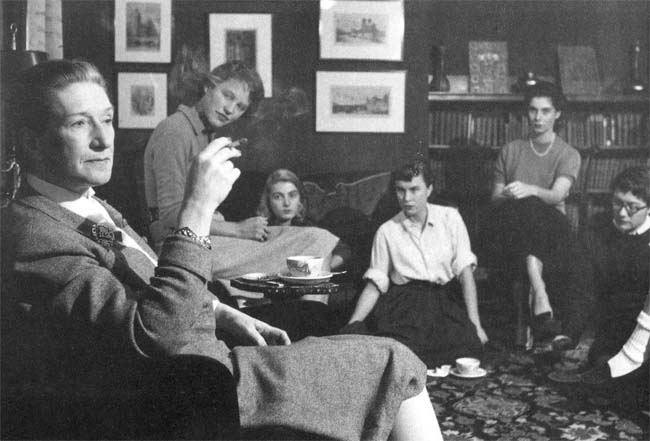

Angle‘s other great inspiration came from the history books. Stegner discovered Mary Hallock Foote while combing through magazines and journals for a chapter he was commissioned to write for the Literary History of the United States. He researched her, uncovered her sketches and writings, republished one of her stories in an anthology, and began teaching her at Stanford. Foote was obscure enough at the time for Stegner to be pretty much the only guy singing her praises. And as it so happened, Foote’s granddaughter happened to be living in Grass Valley.

With the help of Stegner’s student, George McMurray, there were efforts to get Foote’s papers into the Stanford library. The Foote famiily gave them to Stegner, with the apparent pledge that Stegner would publish these and provide typed transcriptions. Ten years passed. There was no traction. Then sometime during the mid-1960s, Stegner decided to take these letters cross-country to his summer home.

He had his mind on a contemporary novel. But the letters nagged at him. So Foote transformed into Susan Burling Ward, who became Lyman Ward’s grandmother. Both the real woman and Stegner’s creation were illustrators and short story writers, with their creative labor in constant demand from the editors of the day. But they were similar in other uncanny ways.

For Stegner had befriended Janet Micoleau, Foote’s granddaughter. Micoleau wanted to see her forgotten grandmother revived and apparently gave Stegner permission to use the papers in any way he desired. Micoeau’s sister, Evelyn Foote Gardiner, was stunned when the letters appeared nearly verbatim in Angle of Repose. Roughly a tenth of the novel includes these letters, opening up a debate over whether or not Stegner was a plagiarist.

Stegner’s indiscretions certainly aren’t on the level of Q.R. Markham. Still, when one learns that Rodman Paul was going to publish a collection of Foote’s letters, Stegner’s response — a letter to Micoleau — does leave the moralist shaking head over Stegner’s swagger:

The question arises, must I now unravel all those little threads I have so painstakingly raveled together — the real with the fiction — and replace all truth with fiction?

If the great novelist here is so great, then why couldn’t Stegner get the reader to believe in the story without using history as a crutch? Does a novel predicated on deceit deserve a Pulitzer Prize and inclusion in the Modern Library canon? Or are all novelists inherently deceitful?

* * *

When I learned about the Foote controversy after reading Angle of Repose, I was surprised to find myself defending Stegner. I might have grabbed the pitchfork if Stegner had plucked the text from one of his contemporaries and attempted to pass it off as his own, but surely some statute of limitations kicks in after a hundred years. Would Foote have received as much attention if Stegner hadn’t written this novel? Since books have a tendency to fall so rapidly out of print, isn’t one method to ensure their long-term survival this type of revitalization?

What’s especially interesting to me is that while Stegner sees no problem being promiscuous with text, his historian hero is intriguingly prudish when it comes to being blunt about what went down with his ancestors:

It happens that I despise that locution “having sex,” which describes something a good deal more mechanical than making love and a good deal less fun than fucking. Also I don’t think anybody’s sex life, Grandmother’s included, very funny, unless you mean funny-peculiar, and Shelly didn’t mean that. She meant funny ha-ha, funny-hypocritical, funny-absurd. I had imagined that Leadville love scene, exceeding my license as a historian, because I felt just then she was fighting against her ingrown gentility and snobbery, ashamed of herself for having been ashamed of her husband, and making contrite and affectionate amends. I had meant that scene to be tender. I meant it to clear away, at least for the time, all the cobwebs. I wanted it to shine the windows and polish the tarnished feelings like a good spring house-cleaning. Which I have known a good love scene to do.

Why on earth did I let some irrational association prevent me from reading Stegner? It’s abundantly clear that he (or rather Lyman) had greater sexual issues to work out on the page.

I forgot to mention Oliver Ward (based on Foote’s husband, Arthur De Wint Foote), who is surely one of the more fascinating entrepreneurial failures in American fiction. Oliver is a man of principle (“I’m an engineer, not a capitalist.”), and this gets in the way of a lucrative scheme to make hydraulic cement that he refuses to act upon. His perpetual failure to mind the store causes him to lose a vital claim that he’s worked much of his life for. And it also makes him embarrassingly passive when he cannot stand up for himself when his hotel reservation is taken away from him and his wife on the way to Leadville, and he is reduced to repeatedly stammering “I’m sorry” when they are forced to hole up in a boardinghouse.

What’s astonishing is how Susan sticks with this man despite his repeat failures — especially when another man, Frank Sargent, Oliver’s most trusted friend, wastes most of his life to be close to her. Do her constant letters to her dear friend Augusta keep her together? Or is there something else that she (or Lyman) is not telling us? She’s hopeful in Santa Cruz (“But Oliver, if thee can make it work, I’d be willing to stay here ten years.”), says “I want this trip to go on being perfect” in Mexico, and is dedicated to her work and family throughout. But when Oliver takes to drink, she asks “Are you even sorry? Are you even ashamed?” and it takes him a good long while to respond. And in light of the terrible fate that Pricey, an Emerson-quoting Englishman who is close with the Wards, suffers, one can’t help but wonder whether Oliver is merely the same man from another angle.

In a time when many married men who have dropped out of the job market or settled for lower stations because the Great Recession has left no place for them, Stegner’s depiction of thwarted masculinity is strangely contemporary.

On the other hand, we have to keep reminding ourselves that this is Lyman Ward’s view of history, not necessarily the full truth of this marriage. If Lyman is so sure that he knows what a good love scene can do, then why is he so opaque about what may have happened between Susan and Frank? If Lyman Ward has any shot of being a bigger man than his grandfather, then why can’t he man up and confront his own failed marriage? That pivotal vantage point within Stegner’s title can apply to just about everything. And if any deep soul is doomed to fight gravity, does this not, in some sense, justify Stegner’s use of the Foote letters? Would not another author or another character have created an entirely different yet equally complex heap of willful obfuscation? Is Angle of Repose the truest expression of Stegner’s character? And if so, should we cut him some slack?

I can ask these questions with confidence. Because I know that the book club story I offered at the beginning is hiding quite a bit that I’m not going to tell you. I have purposefully kept some details nubilous because the mythology, imperfect and imprecise as it is, is mine. If we tell each other stories to live, then do we not also live to tell stories?

Next Up: Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March!

It is easy to forget, as brave women

It is easy to forget, as brave women

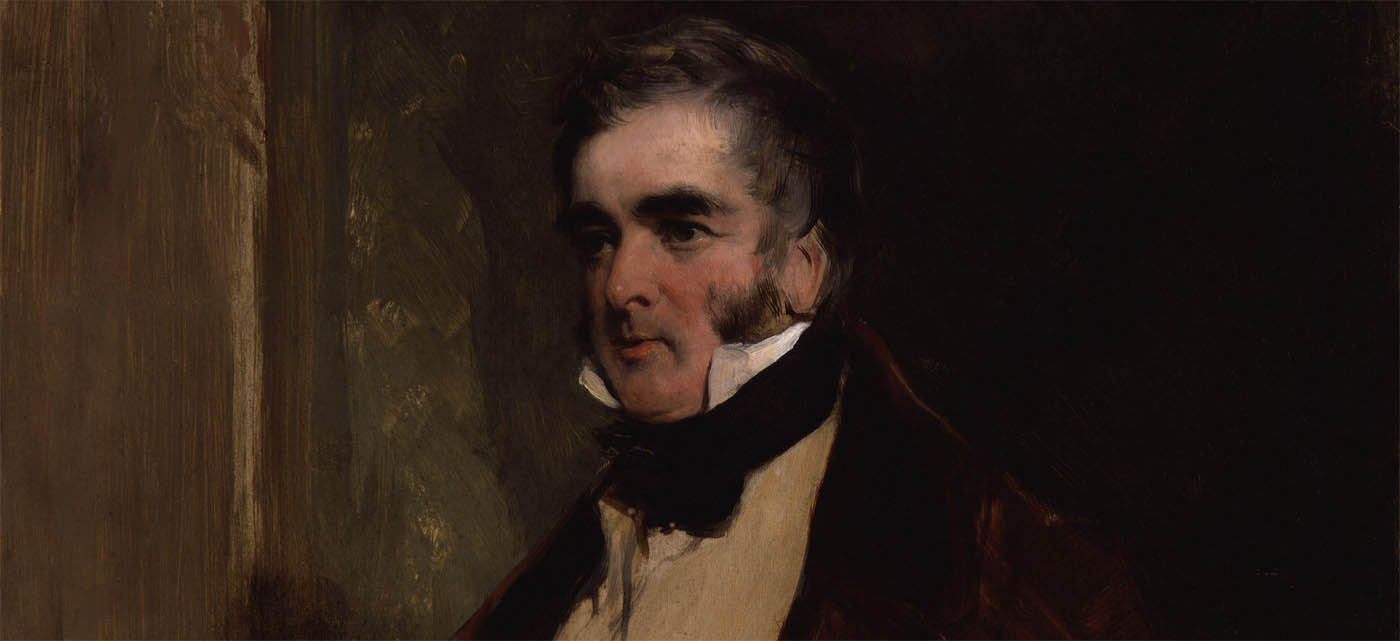

History has produced such a rich pile of devious political figures who spend every spare minute scheming and plotting their rise that today’s aspiring aristocrats, who can be found working every connection to get their kids into bright educational citadels and reliable sinecures, cannot come close to such cutthroat monomania. Yet there are also those who blunder into top office like bumpkins crashing high-class weddings through the simple repetitive act of placing one foot in front the other. William Lamb, aka Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for eight years (1834, 1835-1841) and the subject of Lord David Cecil’s generous biography, was one such man.

History has produced such a rich pile of devious political figures who spend every spare minute scheming and plotting their rise that today’s aspiring aristocrats, who can be found working every connection to get their kids into bright educational citadels and reliable sinecures, cannot come close to such cutthroat monomania. Yet there are also those who blunder into top office like bumpkins crashing high-class weddings through the simple repetitive act of placing one foot in front the other. William Lamb, aka Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for eight years (1834, 1835-1841) and the subject of Lord David Cecil’s generous biography, was one such man.

Three years ago, my jocular compadre Lydia Kiesling

Three years ago, my jocular compadre Lydia Kiesling

Merchant Ivory Productions has been one of the greatest threats to literature during the past three decades. Known for producing well photographed films that put most sane people to sleep, the Merchant Ivory team has demonstrated a remarkable knack for divesting zest from the literary classics. They have ordered esteemed actors across sweeping vistas as if they are unbudgeable bovine who require vast encouragement to produce milk. They have bored more often than seems reasonable. Where Orson Welles’s Shakespeare adaptations or Iain Softley’s The Wings of the Dove or Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon or Sally Potter’s Orlando or William Wyler’s The Heiress or Corman’s Poe pictures or The Royal Shakespeare Company’s nine hour version of Nicholas Nickleby bristle with life and visual excitement, demanding that you get your hands on the source material at once, the Merchant Ivory movies are the cinematic equivalent to visiting the in-laws or steeling yourself up for a dreadful Thanksgiving or attending a funeral for someone you didn’t really know that well.

Merchant Ivory Productions has been one of the greatest threats to literature during the past three decades. Known for producing well photographed films that put most sane people to sleep, the Merchant Ivory team has demonstrated a remarkable knack for divesting zest from the literary classics. They have ordered esteemed actors across sweeping vistas as if they are unbudgeable bovine who require vast encouragement to produce milk. They have bored more often than seems reasonable. Where Orson Welles’s Shakespeare adaptations or Iain Softley’s The Wings of the Dove or Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon or Sally Potter’s Orlando or William Wyler’s The Heiress or Corman’s Poe pictures or The Royal Shakespeare Company’s nine hour version of Nicholas Nickleby bristle with life and visual excitement, demanding that you get your hands on the source material at once, the Merchant Ivory movies are the cinematic equivalent to visiting the in-laws or steeling yourself up for a dreadful Thanksgiving or attending a funeral for someone you didn’t really know that well.

Soak up enough art over the years and you’ll run into the cultural dichotomy, either through half-cocked introspection or cocktail party gunpoint. It’s a practice where two artists of equal merit and/or influence are positioned at opposing ends in talk, much as an oily advertising tyrant pins blindfolds on fat suburban heads to establish the next tasteless drink to slam down lacquered American throats.

Soak up enough art over the years and you’ll run into the cultural dichotomy, either through half-cocked introspection or cocktail party gunpoint. It’s a practice where two artists of equal merit and/or influence are positioned at opposing ends in talk, much as an oily advertising tyrant pins blindfolds on fat suburban heads to establish the next tasteless drink to slam down lacquered American throats.

For more than a decade, I have nursed a grandiose grudge towards Wallace Stegner that has less to do with the eco-friendly West Coast bigshot’s literary streetcred and more to do with my own irrepressible ineptitude concerning matters of the boudoir.

For more than a decade, I have nursed a grandiose grudge towards Wallace Stegner that has less to do with the eco-friendly West Coast bigshot’s literary streetcred and more to do with my own irrepressible ineptitude concerning matters of the boudoir.

There are so many unpardonable cruelties collected in Patrick French’s gripping (and authorized!) biography, The World Is What It Is, that it’s difficult to know where to start in condemning V.S. Naipaul’s boorish behavior, while also praising his prowess on the page. And yet I can’t quite do that either. I’ve read A Bend in the River twice, and I have to conclude that the book’s pat pronouncements about colonialism, even with the adept take on self-deception and willful naïveté, aren’t especially staggering. By the time the shopkeeper Salim shows his colleague Indar around the African town where he lives and reveals how little he knows (“All the key points of the town I knew could be shown in a couple of hours, as I discovered when I drove him around later that morning”), it was abundantly clear to me that he would never know.

There are so many unpardonable cruelties collected in Patrick French’s gripping (and authorized!) biography, The World Is What It Is, that it’s difficult to know where to start in condemning V.S. Naipaul’s boorish behavior, while also praising his prowess on the page. And yet I can’t quite do that either. I’ve read A Bend in the River twice, and I have to conclude that the book’s pat pronouncements about colonialism, even with the adept take on self-deception and willful naïveté, aren’t especially staggering. By the time the shopkeeper Salim shows his colleague Indar around the African town where he lives and reveals how little he knows (“All the key points of the town I knew could be shown in a couple of hours, as I discovered when I drove him around later that morning”), it was abundantly clear to me that he would never know.

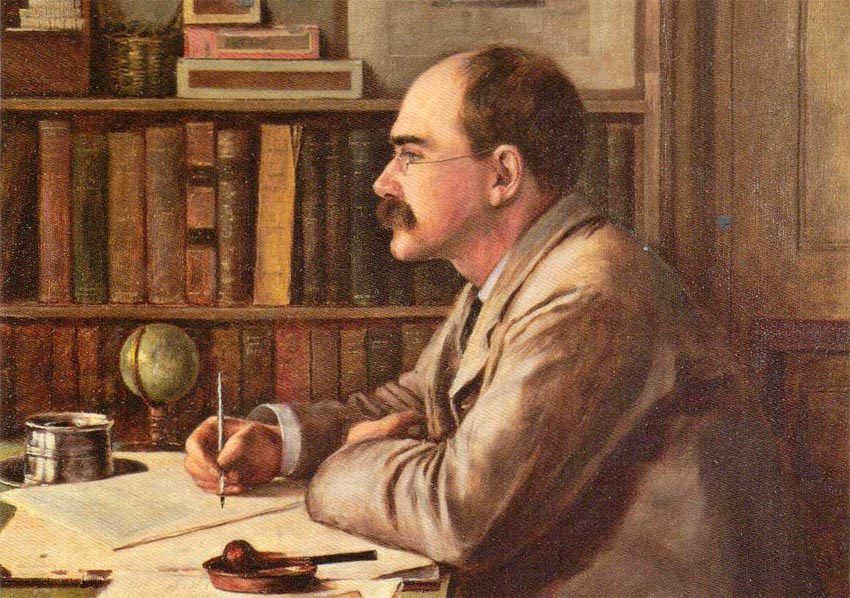

The Times‘s Ben Macintyre

The Times‘s Ben Macintyre

Let’s look back for a second and ponder where the Modernists came from. They came out of my ass. They flew out of my anus like winged monkeys. I assure you that this was a rather unsettling feeling that caused me to apply a good deal of lube when the flesh grew ruddy. They flew out of my ass because I knew they were writing good books and I knew that I couldn’t understand them and I knew that the Modernists were complicated but that they didn’t always think Plot First. Which is a little like Country First. Reading, as we all know, must subscribe to the Sarah Palin doctrine. So forget Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, and all those literary heavyweights that people marvel over. They all came out of my ass and still carry that shiny and confused look. This is why they are dead. It has nothing to do with life expectancy. It has everything to do with my ass.

Let’s look back for a second and ponder where the Modernists came from. They came out of my ass. They flew out of my anus like winged monkeys. I assure you that this was a rather unsettling feeling that caused me to apply a good deal of lube when the flesh grew ruddy. They flew out of my ass because I knew they were writing good books and I knew that I couldn’t understand them and I knew that the Modernists were complicated but that they didn’t always think Plot First. Which is a little like Country First. Reading, as we all know, must subscribe to the Sarah Palin doctrine. So forget Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, and all those literary heavyweights that people marvel over. They all came out of my ass and still carry that shiny and confused look. This is why they are dead. It has nothing to do with life expectancy. It has everything to do with my ass.

The morning started off with Bob Stein, founder and co-director of

The morning started off with Bob Stein, founder and co-director of