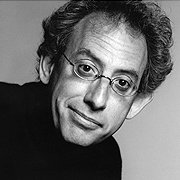

This morning, as the man was midway through packing his carefully prepared clothing and about to check out of his hotel, Ken Kalfus was generous to take some time out of his schedule to talk with me about his book, A Disorder Peculiar to the Country. His novel, which blissfully assaults the “irony is dead” conventions of post-9/11 life, began from a short story. Kalfus is now working on short stories, but it’s just possible that, in his concern for words and language, he’ll find that grand idea that will translate into a third novel.

(And, incidentally, Kalfus will be reading with another 2006 National Book Award finalist, Jess Walter, tonight at Bookcourt at 7:00 PM.)

A good part of our conversation was concerned with the following passage, which Kalfus agreed was one of the key galvanizing points for Disorder:

But Joyce felt something erupt inside her, something warm, very much like, yes it was, a pang of pleasure, so intense it was nearly like the appeasement of hunger. It was a giddiness, an elation. The deep-bellied roar of the tower’s collapse finally reached her and went on for minutes, it seemed, followed by an unnaturally warm gust that pushed back her hair and ruffled her blouse.

Correspondent: So, in this case, it looks like you have long sentences. But they resemble short sentences by way of the comma.

Kalfus: You know, you want these words to go off in the reader’s head in a certain way. You really do. I mean, that’s what you’re trying to do when you write. And sometimes, you do that with commas. Or you do that with sentences. You do it with colons. Semicolons. Whatever it takes, you do.

Kalfus: You know, you want these words to go off in the reader’s head in a certain way. You really do. I mean, that’s what you’re trying to do when you write. And sometimes, you do that with commas. Or you do that with sentences. You do it with colons. Semicolons. Whatever it takes, you do.

Correspondent: Is it largely intuitive? This rhythm that you’re looking for. How much of it is planned through kind of a psychological approach? Do you test this kind of thing on other readers?

Kalfus: No, no, no, no. But there’s a lot of rewriting. I can’t say. If I were to look at it again, I might want to change something in that sentence. It sounded pretty good when you read it. It’s partly intuitive. And then you write it down and it looks like junk. And then you rewrite it again. You know, you go over and over and over it again. So the process is making these sentences work. And, quite frankly, I’ve discovered that’s maybe the easiest thing — the most pleasurable thing about writing — is getting those sentences right. It’s a lot of work, but in a way, maybe it’s the easiest thing. Because you can always tinker with it, tinker with it. Plot and character are actually more — are probably the big things that are more demanding when you’re plotting or you’re putting it out. Making sure that the major parts work. Dealing with sentences, you can always rewrite those little sentences. But once the story gets locked in, it’s hard to shift things.

Correspondent: So, for you, the sentence is more of the motivating factor than the actual plot and the character…

Kalfus: You know what. I can’t answer for everybody. I think we write because we love language. Was Shakespeare really obsessed about Denmark? About succession in Elsinore? Or fathers and sons? He had some ideas for some great lines. And he found a story that he could use. But I think all of us come to writing for the love of language. And the stories come after that. There’s a story when I write a book or a project. But I saw a way of using language in a way that was interesting to me.

Correspondent: Well, that’s a good point. Because people remember Twelfth Night not really for the plot, but “If music be the food of love, play on.”

Kalfus: That’s very awkward to compare myself to Shakespeare.

Correspondent: I’m sorry about that.

Kalfus: But I see an opportunity to use language when I write.