Ever since Samuel Madden responded to Swift in 1733 with the satirical Memoirs of the Twentieth Century, in which letters from a Jesuit-ruled future were magically received in 1728, time travel narratives have proven difficult for many artists to resist. And the audio drama ars PARADOXICA is a terrific one.

Created by Mischa Stanton and Daniel Manning, the program follows Dr. Sally Grissom (played by Kristen DiMercurio) as she records various tapes after inadvertently landing in the early days of the Cold War, forced to work as a wage slave for Uncle Sam and soon finding herself forging friendships and paths to further scientific discovery with other scientists. It is a brainy and sometimes quietly goofy narrative, with null fields, strange small towns, time travel murders, reverse engineered answered machines, and crazed trips to Las Vegas, all buttressed by fantastic vocal work, an expansive narrative, and mysterious numbers that punctuate the end of each episode.

Aside from its growing family of notable characters and surprise plots, one of the reasons why ars PARADOXICA works so well is its careful attention to sound. In the show’s most recent episode, “Anchor,” we hear two characters discussing how “quiet” the 1940s are. This is then followed by a scene in a hotel room that seems a little quieter than one might expect, almost as if the previous reference to silence served as an excuse to avoid hustle and bustle in the mixing. So the listener becomes accustomed to a certain tone, only for that tone to be jarred by events that go down during a road trip later in the episode.

To learn more about the show’s origins, I contacted Mischa Stanton, who was kind enough to answer my many questions over a few weeks. We talked time travel, Stanton’s work as producer on The Bright Sessions, eccentric scientists, and how characters and stories inevitably change no matter how much you plan a grand narrative.

You can listen to the show here and support the show on Patreon. ars PARADOXICA just aired its fourteenth episode, “Anchor.”

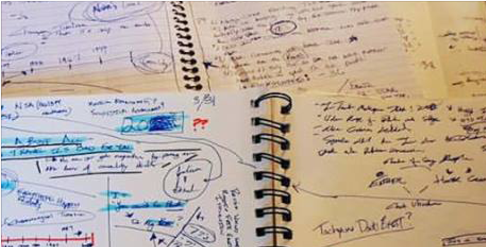

EDWARD CHAMPION: I’d argue that there are two types of time travel narratives: the heady and complicated versions populated by Shane Carruth’s Primer and Donnie Darko and the fun-filled versions seen with Nacho Vigalondo’s Timecrimes and, most prominently, Back to the Future (which ars PARADOXICA has extensively name-checked). Then there are films like Looper and 12 Monkeys (or, for that matter, Audrey Niffenegger’s novel The Time Traveler’s Wife), which split the difference between the two varieties. ars PARADOXICA seems to be aiming for that happy compromise. And in asking the inevitable question about how you and head writer Daniel Manning came up with ars PARADOXICA, I’m wondering if you set out to find a middle ground between heady and entertaining (not that they can’t coexist!). How does audio drama lend itself more towards a viable execution of this theoretical Venn diagram? Had you told versions of this story before? I have seen photos of timelines scrawled out on paper that appear to have been devised by one “Mischa Stanton” (answering to the names of Aaron and Abe?). What did you do to plan for this?

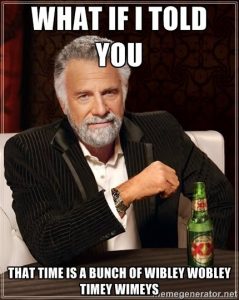

MISCHA STANTON: Wow, I’m really glad we’re hitting the mid-point between relaxed and serious time travel! To be perfectly honest, we definitely set out to make the most dark, the most serious, and above all the most logically-sound time travel story we possibly could. Daniel and I were frustrated by the proliferation of time travel media that had flimsy rules that weren’t based in any sort of reality. The likes of The Butterfly Effect, that movie adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s “A Sound of Thunder,” and Doctor Who. (Oh man, if I never hear the phrase “timey-wimey” again, it’ll be way too soon.) We wanted a world with rules, and a story with strict adherence to those rules. That the show is any funny at all comes from Dan’s writing of Sally (Sally is basically female-Dan) and Kristen DiMercurio’s absolutely killer performance.

MISCHA STANTON: Wow, I’m really glad we’re hitting the mid-point between relaxed and serious time travel! To be perfectly honest, we definitely set out to make the most dark, the most serious, and above all the most logically-sound time travel story we possibly could. Daniel and I were frustrated by the proliferation of time travel media that had flimsy rules that weren’t based in any sort of reality. The likes of The Butterfly Effect, that movie adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s “A Sound of Thunder,” and Doctor Who. (Oh man, if I never hear the phrase “timey-wimey” again, it’ll be way too soon.) We wanted a world with rules, and a story with strict adherence to those rules. That the show is any funny at all comes from Dan’s writing of Sally (Sally is basically female-Dan) and Kristen DiMercurio’s absolutely killer performance.

That said, the way we approach the show is by having the characters go through some seriously heavy and mind-bending business. So the only way to deal with that and still keep the story swimming is to recognize the utter absurdity of the scenario (in our case, the scenario being “a cold unfeeling universe”), laugh, and carry on. That carries over from how I view life, which is that it’s an absurd and cacophonous mess that is almost entirely out of any one person’s control. So you just gotta laugh!

The time travel concept in and of itself isn’t what drove us to audio. In fact, our very first crack at this “brand” of storytelling we’ve cultivated wasn’t even a time travel story at all. The show started as a numbers station (of which listeners can find an example at the end of each episode) that Daniel and I recorded in our dorm at Emerson College, and then snuck onto the radio in the dead of night while no one was listening. It was only after we did it once that we begin to consider, “Okay, why does this numbers station exist? Who is it from? Who is it to?” And from there, we expanded out to “a secret government time travel conspiracy.”

As for how much we have planned, without giving too much away, I’ll say this: We had the last episode outlined before the pilot. I think that’s probably the best way to write a time travel story: write the ending first. That way, all of your logical knots untangle into something concrete at the end. You also get a ton of opportunities to foreshadow plot threads and plant little seeds for later that we, as fans, love to pick apart and unravel.

The weather is 1 degree Celsius in @arsparadoxica: 15 10 4 6 BEEP 24 16 19 12 BEEP 13 16 23 6 BEEP 26 16 22 9 BEEP 20 9 16 24 Danke schoen!

— Edward Champion (@drmabuse) April 25, 2016

CHAMPION: I had a feeling that you and Daniel knew each other, but I didn’t realize how far back the connection went! And it does have me wondering if anybody ever replied to your college radio cryptographic code. (Certainly, I felt compelled to tweet back minutes after listening to the first episode of ars PARADOXICA!) This leads me to wonder how you managed to land the magnificent Kristen DiMercurio and how you went about casting this. Did you rely largely on people you knew? Did you willfully establish a universe with constraints because the best creative work typically emerges out of creative limitations? The fact that you bleep out the year that Sally came from and that you regularly bombard Sally’s diary entries with interference suggests a keen commitment to creative obfuscation! I’m almost wondering how much you folks obsess over the minutest details. The Wooden Overcoats fellows told me that they even have “placeholder” jokes until they can get it right. If you are sitting on a massive pile of paperwork (and I suspect you are!), what freedom do you allow yourself to deviate or improvise — whether in the writing or the recording of ars PARADOXICA?

STANTON: We’ve had a few die-hard fans figure out the codes— which is a lot of fun for us because that just means we get to come up with harder codes! Shoutout to Brian B and Phoebe S, the lead code-breakers out there.

STANTON: We’ve had a few die-hard fans figure out the codes— which is a lot of fun for us because that just means we get to come up with harder codes! Shoutout to Brian B and Phoebe S, the lead code-breakers out there.

aP is actually Kristen’s first voice acting gig! I knew her in college (not super well, but we often attended the same theatre program parties), and she posted on our college’s alumni Facebook group asking if anyone had any leads on classes for voice acting. We messaged her the same day: “Wanna read for a lead role in our show?” And now she’s absolutely blowing up the scene. She’s working with Two-Up Productions on their next thing. She’s playing Selina Kyle in an adaptation of Batman: Year One. She’s getting casting calls left and right for different audio dramas. We really found something special with Kristen, and the show wouldn’t be nearly as good without her.

A lot of the cast are just actor friends of mine. I knew Reyn Beeler, Dan Anderson, Katie Speed, and Lee Satterwhite from college (along with a lot of our “additional voices” cast), and Zach Ehrlich and Susanna Kavee and I go all the way back to high school. The one big find I made outside of my friend group was Robin Gabrielli, who plays Anthony Partridge. I met him through the director of a play I designed back in Boston. Man, is that guy just a treasure. And of course, now that I’m out of college and working in the Los Angeles entertainment industry, I have a much wider base to pull new actors from!

As far as constraints, one of my design heroes, Mark Rosewater, likes to reiterate “restrictions breed creativity.” The blank page can be intimidating. So giving yourself conditions to go by helps to realize your story a long way. That’s why we keep to such strict rules in aP. We think the “Only to the past, not before 1943” framework makes for a more interesting story. But within that, we try to keep an open mind about what is possible. It’s been especially interesting in Season 2, since we’ve opened the world up to a new writing staff. And now they come to me with questions of “Does this work?” or “Can I do this?” or “Will this break the rules?” And it’s great to have clear yes/no answers, to work with the writers to fit their grand ideas into this framework.

Once the scripts are written, the story is mostly locked-in. We do a lot of work with the writers to make sure everything (a) makes sense within the world, (b) sounds consistent with how we want to portray the characters, and (c) sets up the plot threads needed for future stories. However, when I get in the booth with an actor, often we’ll find something that doesn’t make sense or that sounds awkward to say. Or we’ll find a leftover line from a previous edit that doesn’t fit anymore and we change it up. We’re not married to the text of each individual line. I’ve also recorded whole scenes and then cut them in editing (usually I run this by the writer first). “No scene is worth a line and no show is worth a scene,” as Daniel likes to say!

CHAMPION: I presume that some of the newer actors, such as L. Jeffrey Moore and Alexander Cole in “Asset,” are people you haven’t known before. How did you go about finding actors once your creative universe started to expand? What difference is there in working with someone you’ve known for a long time and someone new? Have you had to make adjustments when, say, Kristen wasn’t available for an episode? One common suggestion I’ve heard among radio drama producers is “Don’t look at your actors” and I have to confess that, while this is eminently pragmatic and sensible, it does suggest a queasy parallel to certain big name Hollywood actors who secure guarantees that crew members should never give them eye contact when they are on set. Given that eye contact is pretty damn essential in talking with and working with people, even for something that is designed for the ear, what do you do to cultivate an atmosphere of intimacy? How have you become better at directing the actors? Have you ever had to bend the draconian rules that you and Daniel established at the beginning to serve the characters?

STANTON: As we’ve expanded our cast (and we have a huge cast) I’ve relied on people I know, or friends of people who are already involved. I met Jeff through Robin Gabrielli, Alex is a fellow audio producer. I was the audio engineer for a musical produced in LA written by Rebekah Allen, who plays Bridget in Episode 13. There was a similar case with Arjun Gupta, who will be in Episode 14. Collaborative art forms, especially audio drama, are all about building your networks outward until you find who you need. Fortunately, the audio drama community has been incredibly welcoming!

I have never heard about “no eye contact,” but I wouldn’t subscribe to that even if I had. A lot of our recording sessions are done by remote. Rather than send an actor off to record on their own, I almost always schedule a time to read with them over Skype. I find it creates a much more personal experience for the actor, which translates to their relationship with the audience in a tangible way.

When we started, I had absolutely no experience directing voice actors. I learned everything I know while creating this show. The biggest lesson I’ve learned is knowing what you want going in and not being afraid to ask for this plainly and without fear. You also shouldn’t be afraid to re-take a line until you’re satisfied!

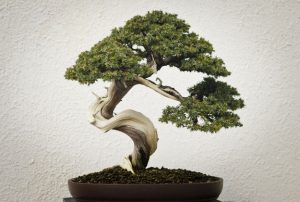

Fortunately, we’ve only had to bend the script to accommodate an unavailable actor once. And even then, the actress had recorded material previously that we were able to use. As far as bending the story, I like to think of it as a bonsai tree: We can bend as we move forward. But once we make a bend, we have to stick to it. What comes before, even the bends, become the solid foundation for everything that comes after.

Fortunately, we’ve only had to bend the script to accommodate an unavailable actor once. And even then, the actress had recorded material previously that we were able to use. As far as bending the story, I like to think of it as a bonsai tree: We can bend as we move forward. But once we make a bend, we have to stick to it. What comes before, even the bends, become the solid foundation for everything that comes after.

CHAMPION: So your story is as naturally expansive as matter contending with repulsive gravity! Since we’re finding a cosmological constant of sorts and since you’ve previously expressed how you put a hard foot down on “timey wimey,” I’m wondering what you’ve done in the name of research. Do you have any salivating physicists trapped in a closet who are willing to unpack entropy and effective field theory for a few scraps of food? Have you relied on any particular books or texts? I get a general Harvard-MIT vibe (a good one, not an obnoxious one!) from ars PARADOXICA and I’m curious what background you, Daniel, and your nimble gang of collaborators have in science? Do you ever find that the dramatization of science or theory gets in the way of exploring characters? Perhaps this was one reason you had the team go to Vegas?

STANTON: I can tell you straight off that we only barely have a background in science. As far as formal training goes, I studied psychology and psychoacoustics (the study of sound perception) in college, and I’m an audio and acoustical engineer by trade; and Daniel like…got an A- in 10th grade Chemistry. Beyond that, the only things we know about particle physics and entropy are what we’ve researched for the show, and most of that was just hours and hours combing Wikipedia articles and their sources (here’s a pro tip for anyone writing a college paper: don’t cite Wikipedia, cite Wikipedia’s sources). I’ve never considered myself a scientist. I’m more of an artist heavily influenced by scientific discoveries, information, and techniques.

The Vegas episode (03: Trinity, Acts I & II) was definitely a point where writing the story butted up against our lack of formal scientific training. In that episode, the characters have to present time travel as a viable tool for the US government muckety-mucks, and then spend weeks trying to devise a presentation. But we found while writing the episode that we couldn’t actually come up with a viable presentation to even write into the show! We had the same struggle as the characters in creating a formal time travel presentation that wasn’t just sleight-of-hand. So that’s what we had the characters do. In the end, they just do some sleight-of-hand. And it doesn’t work. They fail their presentation. The program shuts down. And they end up having to move to a tiny town in Colorado. So in that way, the science and our understanding of it (or lack thereof) really informed the direction of the entire show.

That said, we wrote Episode 03 in the very first batch of scripts, before we even had Kristen on the show, before it was out in the world. Working with the show out in the world for over a year now has given us a better grasp on what we can and can’t do. And I’m proud to say we’ve finally figured out how to design some really cool time travel experiments. Stay tuned for Episode 15, I’m really proud of it.

CHAMPION: You also produce The Bright Sessions and I’m terribly curious about (a) how this happened, (b) how working within another person’s vision differs from what you and the gang have established at ars PARADOXICA, and (c) what you did to make Lauren’s job easier? Was there anything she wasn’t doing that you implemented?

STANTON: I found The Bright Sessions as a fan first! I was trying to find other shows like ours, and I kept seeing people mention The Bright Sessions, so back in March I listened to the first season on a plane ride. I was hooked. And then there was a mid-season announcement on her feed, where Lauren said that if she made enough Patreon money she’d be able to hire an audio producer who actually knew audio. And I said to myself, “I’m an audio producer!” So I emailed Lauren the next day offering to jump in with her. She’s got the acting and directing stuff down, but she wasn’t as well-versed in the audio production, the mixing, the creation of sound effects. So I’ve helped prop up what she doesn’t know, so that she has been able to tell bigger and more ambitious stories. Before I started, the show was still mostly two people in a room. But once I joined she was able to give her characters more things to do and more space to do them in. As I checked my email to respond to this question, Lauren just sent me confirmation that The Bright Sessions #24 (“Zero Hour,” her Season 2 finale) is ready for launch. And, of course, your readers will have already heard it by the time this interview comes out. So they’ll know that it’s our most ambitious episode yet.

STANTON: I found The Bright Sessions as a fan first! I was trying to find other shows like ours, and I kept seeing people mention The Bright Sessions, so back in March I listened to the first season on a plane ride. I was hooked. And then there was a mid-season announcement on her feed, where Lauren said that if she made enough Patreon money she’d be able to hire an audio producer who actually knew audio. And I said to myself, “I’m an audio producer!” So I emailed Lauren the next day offering to jump in with her. She’s got the acting and directing stuff down, but she wasn’t as well-versed in the audio production, the mixing, the creation of sound effects. So I’ve helped prop up what she doesn’t know, so that she has been able to tell bigger and more ambitious stories. Before I started, the show was still mostly two people in a room. But once I joined she was able to give her characters more things to do and more space to do them in. As I checked my email to respond to this question, Lauren just sent me confirmation that The Bright Sessions #24 (“Zero Hour,” her Season 2 finale) is ready for launch. And, of course, your readers will have already heard it by the time this interview comes out. So they’ll know that it’s our most ambitious episode yet.

I’ve been working in collaborative theatre environments for twelve years. So designing to someone else’s vision is actually pretty par for the course for me (that I have so much more creative control on aP than I usually do is probably why I push so hard with it). Lauren is an amazing boss. She has such a clear pictures of these characters in her head. It’s like they’re all real people she knows and hangs out with, but that I’ve never met. She always knows exactly what she wants, even if she doesn’t always have the best words to describe it. We’ve developed a lot of trust. So she gives me a lot of freedom to craft the soundscapes of the show. But that’s my job! Lauren asks for a mood, a general feel to the episode (or she suggests it in her writing) and it’s my job to take that mood and interpret it as a soundscape. That’s what a sound designer does: takes the tool of sound, and uses it to provoke emotional responses to tell a unified story. (Are you listening, Tony Awards?)

CHAMPION: I should probably disclose that I am terribly fond of fun dramatizations of science and scientists, whether they hit the more eccentric strains seen with John Noble’s Dr. Walter Bishop in Fringe, Dr. Emilio Lizardo in The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai, or Dr. Herbert West in Re-Animator or the more straight-laced eccentric seen with Jeff Goldblum’s Dr. Seth Brundle in The Fly, Dr. Hubert J. Farnswoth in Futurama, or (more medical than physics) Dr. Dana Scully in The X-Files (which seems to be the closest model for Dr. Sally Grissom). What impresses me about ars PARADOXICA is how you’ve rooted Dr. Grissom in reality and that scientists as a whole don’t fall into the authoritative eccentric model that we’ve become so accustomed to. I’m very interested if any of this factored into the writing and devising of these episodes, even before you had Kristen. To what degree is your background in acoustics responsible for a similarly dogged commitment to the real? (The Truth‘s Jonathan Mitchell also has an extensive audio and music background, which I suspect is heavily responsible for that marvelous program’s commitment to grounding his stories in base reality.)

STANTON: I think stories have a tendency to boil down a knowledgeable character into a one-dimensional role— “the Scientist/the Smart One.” And with good reason. It’s a great exposition machine when you need the story to move along, especially in media where you’re on a strict time limit like TV. Cop shows do this a lot with the ME/Coroner character, just as a way to spit out pertinent medical information and move the plot forward. And then, often to give a bit of color to it, a producer will throw in a generalized “eccentricity,” as you call it, to make the character at least partly memorable. But with a show like ours, something that is all about the science and how it affects the people close to it, being smart or being a scientist is a given. So yeah, Esther is smart, but she’s also caring, calculating, judgmental, and ambitious. Yeah, Sally’s a scientist, but she’s also a movie lover, a stranger in a foreign land, and an amateur comedian (one of our tenants of writing Sally is “she thinks she’s hilarious”). When “scientist” is the norm, there’s no need to stick to the trope. So it gives us far more room to play in.

A lot of what our show explores is the morality of discovery. I’ve often said that science tells us what we can do. But it’s up to humanity to decide what we should do. Often you don’t know what you should do until you’ve already made a mistake. I think that’s part of what makes Sally such an interesting character to listen to. She invented this time machine entirely by accident and, before anyone could ask her what she thinks should be done with the technology, the tech is already in the hands of one of the most powerful governments on Earth in the middle of a war. So a lot of the show is Sally reconciling her love of unbounded discovery with the fear of moving ahead too fast, before she’s able to consider the consequences of her actions.

As far as my own acoustical background, I think that’s what allows me to imagine what a room sounds like, to determine which elements are vital to conveying action and which ones just get in the way. Wherever I go, I always take a moment to listen to a room and break apart the tone into pieces for later use. For example, in Episode 13, there’s a moment where two characters travel from drinking in a crowded bar in New York City to post-sex in an empty apartment. For me, setting up that scene meant: (1) muffled city noise behind the apartment walls, (2) heavy breathing, (3) rustling bedsheets, (4) grabbing a lighter and lighting a cigarette. These moments are all disconnected pieces when you listen to them individually. But when put together there’s really only one thing that could have happened in the intervening space. And that’s the trick to building convincing scenes in audio drama. It’s not just finding the right sound effects. It’s finding the exact combination of elements that can only mean what you want these to say.

And thank you so much for that comparison! Jonathan is an incredible artist, and The Truth was a huge inspiration to me. I had just picked it up as I was mixing our first episode. It really showed me what a podcast can do, and pushed me to make aP even better.

CHAMPION: I completely detected the “she thinks she’s hilarious” vibe from Sally as she records her diary entries, which is a peculiar cousin to loneliness. It’s not unlike the relentless pop cultural references that fuel Eiffel’s monologues in Wolf 359. Eiffel believes he’s a standup comic to some degree, but he’s also deeply flustered in deep space. In my conversation with The Bright Sessions‘s Lauren Shippens, we discussed how the natural intimacy of radio often lends itself to this therapeutic feeling, almost as if you’re eavesdropping upon a rather naked portrait of human emotions. With Sally, we often have her zest colliding with her frustration and ennui, almost as if she’s masking her true feelings as dutifully as you’re bleeping out the year she came from. How long can you sustain these emotional revelations by omission in a long-running serial? Was this one of the reasons you juxtaposed Sally’s life and explorations with the tension between Partridge and his wife? Also, the two-part episode “Consequence” almost tips the balance of the show altogether by showing another side of Partridge and the larger panorama of the research program. And it does have me wondering if much of this episode (and ars PARADOXICA as a whole) was designed to avoid what I call the Cuse-Lindeloff Enigmatic Storytelling Paradox, whereby a series dollops endless mysteries to rope the audience in, keeps bombarding the audience with more mysteries (perhaps as seductive as the earlier ones) while failing to resolve the previous mysteries, and only succeeds in infuriating the audience for not resolving story strands either fast or satisfyingly enough. The audience comes to resent the show and the mysteries, wondering why they bothered to tune in altogether, and turns their pitchforks on the creators for their storytelling gaffes. You alluded earlier to having a vision for the ending. While it’s impossible for any producer to anticipate the full extent of how an audience reacts, you do have a massive story. And I’m wondering the extent that you’ve addressed or anticipated this!

STANTON: We are definitely reaching a tipping point with Sally. She’s resilient, but… Okay I really don’t want to give anything away. But we’re not ignoring the compounded effects of the utter heaps of tragedies that our show has been heaping onto her. The next few episodes are really going to bring that to a head.

As for why she masks her feelings that way? That’s a byproduct of Sally being basically an amalgam of Daniel, Kristen, myself, and someone who actually knows science. I think that the three of us have a lot of zest, a lot of ideas we want to explore and a lot of things we want to say and do, as well as a lot of frustration with the world we’re living in. So we use pop culture, just like Sally does (or wishes she could) as a place that is comfortable to hide our true feelings about everything going on around us. And I think you can probably say that about a lot of people right now.

And that’s coming through in a bunch of audio dramas as well. A lot of shows, like Welcome to Night Vale and The Black Tapes and Small Town Horror, are all about living on the very edge of the unknown and getting your hands and your mind around it, trying to make some sense of the world. A lot of the things about the world that I believed to be true changed as I grew up in it. Now I think that a lot of us don’t know what to expect anymore. But we don’t want to hide from the world. So the only other option is to embrace the unknown. And pop culture references.

As for “Consequence,” Season 1 (and yes, the show from start to finish) was 100% a response to the kind of storytelling that use questions first and answers maybe. All of our questions have answers. Of course, we adapt that answer to what happens in the middle, but we are always moving toward the answer. I want our fans — or people who invest hours of their time and thought to us at the very least — to be satisfied that what we’ve built was always with purpose. I want our ending to seem unexpected yet inevitable.

CHAMPION: “Signal”‘s journey through airports allowed us to learn a few qualities about Sally — that she smokes, that she prefers jeans to sweatpants (which the part of me that bemoans sweatpants as the default American sartorial choice was pleased to learn!). And I am curious about the extent that you have worked out little personality quirks with the actors. Obviously, a story as intricate and imbricated as ars PARADOXICA is going to serve plot more than character. But how much character work do you do? Do you and Daniel struggle sometimes to find character moments? And how fixed are the answers to your questions? Have there been any radical shifts that you’ve made during the course of production? Has a read on a take ever drastically altered your story?

STANTON: I’m not sure if she smokes as a habit! Of course a lot of people did in the 40s so she may have picked it up, but she does know how bad it is for her. No, I think we wrote that in because it’s something you can’t do on planes now, and Sally is, above all, a rebel.

We’ve built the characters slowly over time. In the beginning we didn’t know much. But after casting, the actors’ readings of the scripts definitely changed how we portrayed them. Esther Roberts wouldn’t be half as interesting if it wasn’t for the amount of work Katie Speed has put into the show. Now she might be my favorite character. Chet Whickman was supposed to be a one-off soldier guy, but when Reyn [Beeler] came to record, he had put such thought and care into his performance that we knew we had to keep him on.

Our answers are usually fairly set things, but the path we take to get there is mutable. For instance, we thought we were going to stay in Polvo New Mexico for a lot longer (as an analogue to the Manhattan Project). But then we rewrote Episode 03 so that they failed in their presentation and the town got shut down, which informed a lot of how we wrote the rest of Season 1 — coming from that place of failure as opposed to being in the successful environment they had in Polvo.

CHAMPION: What’s the biggest blunder you made in the first season? What would you do differently? What’s the biggest piece of advice you could offer to any emerging audio drama producer?

STANTON: I don’t really have a great answer to this. We never made one big blunder. It just felt like a rolling series of tiny blunders. Errors in pre-planning, in communication, that made us scramble to meet deadlines a couple of times. Errors in marketing, and in how we set up the technical back-end. Not knowing my software as well as I could. aP is the first audio drama we’ve made, we’re so new to the medium, I learned so much making that first season. And I think that’s the biggest piece of advice I can give: You’re not going to get everything right the first time, or even the second time. It’s really important to forgive your own mistakes as you’re learning.

I think Ira Glass really said it best:

All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But it’s like there is this gap. For the first couple years that you’re making stuff, what you’re making isn’t so good. It’s not that great. It’s trying to be good, it has ambition to be good, but it’s not that good. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is good enough that you can tell that what you’re making is kind of a disappointment to you. A lot of people never get past that phase. They quit.

Everybody I know who does interesting, creative work they went through years where they had really good taste and they could tell that what they were making wasn’t as good as they wanted it to be. They knew it fell short. Everybody goes through that.

And if you are just starting out or if you are still in this phase, you gotta know its normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. Do a huge volume of work. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week or every month you know you’re going to finish one story. It is only by going through a volume of work that you’re going to catch up and close that gap. And the work you’re making will be as good as your ambitions.

I took longer to figure out how to do this than anyone I’ve ever met. It takes awhile. It’s gonna take you a while. It’s normal to take a while. You just have to fight your way through that.