Megan Abbot is most recently the author of Dare Me. She previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #404.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

This episode of The Bat Segundo Show is brought to you by Audible.com. If you want to listen to Megan Abbott’s Dare Me, and help keep this show going, sign up for a free audiobook and a 30 day trial. Use this handy link: http://www.audiblepodcast.com/bat

This episode of The Bat Segundo Show is brought to you by Audible.com. If you want to listen to Megan Abbott’s Dare Me, and help keep this show going, sign up for a free audiobook and a 30 day trial. Use this handy link: http://www.audiblepodcast.com/bat

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Preparing to shake the appropriate pom-poms.

Author: Megan Abbott

Subjects Discussed: Secret conversations, how cheerleaders are depicted in American culture, Bring It On, cheerleaders and postmodernism, parallels between cheerleaders and soldiers, doing research almost exclusively online, how fonts and italics reinforced text message culture in Dare Me, the text message as a noir voice, theories that Dare Me started off as a recession novel, teenagers and technology, creating a sad and bleak adult world, logical reasons for why teenagers have no desire to have grown-up jobs, empty apartment buildings, people who die in luxury condos, balancing literary and mystery elements to create a transitional novel, stretching genre, crime as a tool for power relations, using Richard III as a narrative framework, obsession with Shakespeare, the Ian McKellen version of Richard III, Looking for Richard, Richard III as an innocent, the ugliness of ambition, desperation, Deadwood, how political theory and Henry IV and Henry V share much in common, Robert Caro, parallels between mean girl rhetoric and LBJ’s profanity, being afraid of individuals who open their mouths, carryover from The End of Everything of a teenage world as an adult one, Fast Times at Ridgemont High, when parents are irrelevant, what Facebook reveals about teenagers, powerful coaches, how tired men can be manipulated, similarities between Dare Me‘s Coach and Queenpin‘s Gloria Denton, how belief encourages people to commit crimes, true crime, the Aurora shootings, the 1984 San Ysidro McDonald’s massacre, the difficulties of relating to a sociopath, the short story that Dare Me sprang from, writing with a manageable evil, the smartphone as a person, how smartphones plague society (and how much we can resist them), teenagers who aren’t aware of the off button, Facebook trash talk, teenagers who crave for attention, writing about cheerleaders who have no interest in boys, relationships between football players and cheerleaders, cheerleaders as a roving gang, teens excited by the National Guard, smoking and drinking in the classroom, cheerleading coaches who are former cheerleaders, physical brutality, the difficulties of writing physical action, finding a new set of words to describe cheerleaders, using multiple verbs in a sentence, eccentric verbs, how any type of sport creates a new language, contending with copy editors, hockey subculture, The Mighty Ducks, Slap Shot, and tennis espionage.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: Now we are sort of doing this secretly. We’ve tried to flag down a waitress to be polite. So it’s very possible we may have to order during this conversation. However, we will talk. Let’s see what we can do.

Abbott: That sounds good. I’m ready.

Correspondent: So let’s start off. I saw that you wrote a New York Times piece about Bring It On. But you use this piece to point out to certain realities of how cheerleaders are depicted in our culture. You point to the portrayal of cheerleaders in two modes: Ironic and Ideal. I’m wondering if some fulfillment of these two criteria is actually necessary to have a plausible narrative these days. What are your thoughts on this? And maybe this is a good way of describing how you zeroed the needle for Dare Me.

Abbott: Right. And I admit. I’m completely vulnerable to both. I love both the Ideal and the Ironic. Every cultural reference I had in there are things I kind of love. You know, Twin Peaks and all the doomed beautiful perfect cheerleaders who become corrupted? I love. And I love all the ironic ones. Some more than others. But it just seems — I mean, the word I didn’t use in the piece, that I avoided using, is “postmodernism.” But that’s essentially what has overtaken the cheerleader. She doesn’t exist as a person and probably never did. So when I actually started to look at actual cheerleaders, the divide fell even greater then in my day in the 1980s, when they were still somewhat enmeshed. Cheerleaders themselves were responding to the idea that they were cheerleaders and they should act as cheerleaders in popular culture did.

Correspondent: Cheerleaders cheerleading about themselves.

Abbott: Exactly! Exactly. But I don’t think that’s true at all today. And I think that “serious” cheerleaders — and I shouldn’t air quote that, but I did. Because they are serious.

Correspondent: Real cheerleaders. Bona-fide cheerleaders.

Abbott: I think they’d line themselves up much more to gymnasts, to serious athletes. And then that’s the parallel. And I would even take it further. When I look at them, I see them as more closely associated with Marines, boxers, the great risks like pilots ready to go down.

Correspondent: That’s very good. (laughs)

Abbott: Kamikazes. I think that there’s even more interesting aspects to them than being hard-core athletes.

Correspondent: So we should be making World War II movies with cheerleaders in place of the soldiers.

Abbott: Seriously. I actually thought about it writing the piece. Because you know how those old movies, they’d always have the guy from Brooklyn and the Oakie. Etcetera.

Correspondent: The Longest Day with cheerleaders.

Abbott: Yes! Exactly! Oh my gosh. That’s such a great pitch. (laughs)

Correspondent: We could make a million dollars on that.

Abbott: Seriously. Right here.

Correspondent: Well, the ironic mode, however, I would say that given the fact you have cheerleaders who are purging, who are regurgitating — in fact, one common motif that you repeat, I think three times in the book, is the hair behind the head as they puke into the toilet. To a certain degree, that is ironic in light of the physical robustness of these cheerleaders. Also the lemon tea diets and all that. So I would argue that perhaps you are working in some ironic mode in the sense that you’re taking a very feminine ideal and hardening it up to some degree to that same level that we generally put football players or, as you point out here, military people and so forth.

Abbott: Right. And I think that the eating disorders — the various bad eating habits, let’s say — of the girls has to do more with making weight like wrestlers than with girls wanting to have perfect bodies. And that sort of extremism is what really interested me. But it also became interesting because I was not a cheerleader.

Correspondent: You weren’t?

Abbott: No. I couldn’t imagine. (laughs)

Correspondent: But you came in with your pom poms and everything.

Abbott: I know. A skirt on.

Correspondent: You’ve been deceiving me the entire time!

Abbott: I know. Afterward I’ll show you that I…

Correspondent: Oh, I see. I brought my little barrette to twirl.

Abbott: Oh! Good, good, good! I will be dandling. It just strikes me that it’s almost like cheerleaders are a metaphor for being a girl. Because usually they do things girls do. But the cheerleader is the heightened form of it. Girls suffer mightily in high school. They do bad things to themselves and others. They torture each other. There was always this great Seinfeld joke that stuck into my head about how terrible boys are in high school, and Elaine says, “Oh, we never treated each other like that. We would just tease each other until we gave each other eating disorders.” And that always struck me as really true. So that the cheerleader — in my case, I am sort of metaphorizing it or ironizing it in some way. Because it’s a stand-in for how hard it is being a girl.

Correspondent: Well, let’s talk about the research that you did. I know that you have said that you have observed various cheerleaders practice. Was this actually in person? Was this on YouTube?

Abbott: It was all online.

Correspondent: It was all online!

Abbott: Yeah. All YouTube.

Correspondent: Did you talk to any cheerleaders at all?

Abbott: I did.

Correspondent: Okay.

Abbott: Via email only.

Correspondent: Oh really?

Abbott: Well, you know, I’m not a journalist, nor do I pretend to be.

Correspondent:> But you play one on TV.

Abbott: I do! Exactly. (laughs) And I guess part of me — I felt, even in my email interviews, that they were performing for me in a way. I wasn’t really seeing them as they were. I would be an intruder. So online, or watching them online or watching them on message boards, where they didn’t know anyone was listening, seemed to be the purest and most authentic view I could get. When they didn’t care. Because they’ll post their practices. They’re performing. So they will always be performers. But I just felt like I was getting a more authentic view of it. And then, at a certain point, I didn’t want to talk to any of them. Because it might change things. My version of it is very heightened. And once I decide how I wanted the world in the book to be, I didn’t want any…

Correspondent: Realism to get in the way.

Abbott: The hyperreality of the book.

Correspondent: So that’s interesting. It seems to me that you were almost collecting textual snippets through these email interviews. Because the book is very heavy on text messages and, in fact, there’s one interesting thing. You have the iPhone font and the italicized font of something from a previous statement. And I’m wondering what this did to get this hyperreal mode that you devised, after soaking yourself so much in cheerleading culture from before.

Abbott: Right. From the beginning, I was so worried about the texting. Because I thought, “How am I going to? Nobody wants to read texts in a novel.”

Correspondent: Nobody’s going to text you. (laughs)

Abbott: Exactly.

Correspondent: You can’t pretend to be a cheerleader.

Abbott: No. And there’s nothing more depressing than reading texts. Because they’re so meant for some kind of quick communication. But once I realized it as a mechanism for the way that girls could torture each other, the way that they could be present, when people can be present when they’re not present. You know, there’s a scene where one of the cheerleaders keeps sending texts to the main girl, Addy. So it’s almost like she’s there. But she’s not there. So the text and the snippets became this opportunity to be the voices in the head. Or the classic noir voiceover. Or the voice over the shoulder. The tap on the shoulder. So once I found a way to turn it into something else, I felt that it had become mine somehow.

(Photo: John Bartlett)

The Bat Segundo Show #474: Megan Abbott (Download MP3)

Weiner: I hope we talk about that.

Weiner: I hope we talk about that.

Williams: We all have these substances coursing through our bodies. Unfortunately, some of them really collect in fatty tissue in the breast. And then the breast is really masterful at converting these substances into food. So it ends up in our breast milk. But I would point out that I did continue breastfeeding. I was convinced that the benefits still outweighed the risks. And, of course, formula is not a completely pure product either. It’s also contaminated with heavy metals and pesticides and whatever else is in the water that you’re mixing it with. And then, you know, of course there are sometimes these

Williams: We all have these substances coursing through our bodies. Unfortunately, some of them really collect in fatty tissue in the breast. And then the breast is really masterful at converting these substances into food. So it ends up in our breast milk. But I would point out that I did continue breastfeeding. I was convinced that the benefits still outweighed the risks. And, of course, formula is not a completely pure product either. It’s also contaminated with heavy metals and pesticides and whatever else is in the water that you’re mixing it with. And then, you know, of course there are sometimes these

Correspondent: Well, the problem we have here too — and this is really frustrating. David Simon, for example, recently

Correspondent: Well, the problem we have here too — and this is really frustrating. David Simon, for example, recently

Kandel: I think what is really so important is, as you pointed out, that there was an interaction between science, literature, and arts that was really unusual. And this began with the School of Medicine, which had great leadership at that time. Under the leadership of a guy called Rokitansky who introduced modern scientific medical practice by developing clinical/pathological correlations to a more systematic way than it had ever been. He felt that when you listened to a patient’s heart and you hear an abnormal sound, you don’t know which valve it’s coming from or exactly what is the disorder of the valve. And so he collaborated with a clinician. And the clinician described the patient’s sounds from the heart and the lungs in great detail. But if the patient died, they collaborated together to do an autopsy on him to figure out exactly what valve was involved and how. And that gave rise to the scientific medicine we now practice. And Rokitansky realized that the truth is often hidden from the surface. And you have to go deep below the surface to get there.

Kandel: I think what is really so important is, as you pointed out, that there was an interaction between science, literature, and arts that was really unusual. And this began with the School of Medicine, which had great leadership at that time. Under the leadership of a guy called Rokitansky who introduced modern scientific medical practice by developing clinical/pathological correlations to a more systematic way than it had ever been. He felt that when you listened to a patient’s heart and you hear an abnormal sound, you don’t know which valve it’s coming from or exactly what is the disorder of the valve. And so he collaborated with a clinician. And the clinician described the patient’s sounds from the heart and the lungs in great detail. But if the patient died, they collaborated together to do an autopsy on him to figure out exactly what valve was involved and how. And that gave rise to the scientific medicine we now practice. And Rokitansky realized that the truth is often hidden from the surface. And you have to go deep below the surface to get there.  Correspondent: Sure. Well, let’s talk about Egon Schiele. His self-portraits in the book, many of which expressed, as you were saying here, this eroticism, this anxiety. In the case of Self-Portrait with Striped Armlets, it depicts him as a fool. He depicts himself as a fool. So his anxiety may very well evoke this fear in the beholder, or the viewer. But there’s a difference between what Schiele experienced and what he chose to express. So it’s possible that he may have exaggerated or distorted.

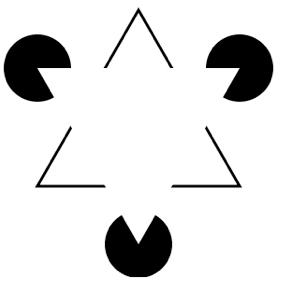

Correspondent: Sure. Well, let’s talk about Egon Schiele. His self-portraits in the book, many of which expressed, as you were saying here, this eroticism, this anxiety. In the case of Self-Portrait with Striped Armlets, it depicts him as a fool. He depicts himself as a fool. So his anxiety may very well evoke this fear in the beholder, or the viewer. But there’s a difference between what Schiele experienced and what he chose to express. So it’s possible that he may have exaggerated or distorted. Correspondent: The key element in assessing the relationship between art and neuroscience is the beholder. Now Semir Zeki has argued that the Kanizsa triangle, where we see these three…

Correspondent: The key element in assessing the relationship between art and neuroscience is the beholder. Now Semir Zeki has argued that the Kanizsa triangle, where we see these three…

Correspondent: Let’s get into this. You point out that George McGovern is one of the key figures responsible for Democratic timidity in relation to the sexual counterrevolution. You suggest that McGovern losing his temper, telling a voter to kiss his ass — that was one factor. The really terrible decision he made involving ordering milk with a liver sandwich in a Jewish deli. Not exactly the smartest choice. There was also this idea that McGovern, because he encompassed this cultural radicalism and failed, that this was what encouraged the Democrats to backpedal. So I’m wondering to what degree is this political temperament and to what degree is this, I suppose, a cultural radicalism that Democrats are afraid of? I mean, 2004, you have Howard Dean’s famous scream. And even before that, everybody was like, “Wow, this guy’s finally standing up for progressivism.” I mean, it seems to me that if you have a situation where the Democratic presidential candidates are limited in what they can say and how they can act, that this kind of progressive idea of, say, supporting something like the Equal Rights Amendment, you’re almost not allowed to do that. So how did this state come to be and what solutions do we have for the future?

Correspondent: Let’s get into this. You point out that George McGovern is one of the key figures responsible for Democratic timidity in relation to the sexual counterrevolution. You suggest that McGovern losing his temper, telling a voter to kiss his ass — that was one factor. The really terrible decision he made involving ordering milk with a liver sandwich in a Jewish deli. Not exactly the smartest choice. There was also this idea that McGovern, because he encompassed this cultural radicalism and failed, that this was what encouraged the Democrats to backpedal. So I’m wondering to what degree is this political temperament and to what degree is this, I suppose, a cultural radicalism that Democrats are afraid of? I mean, 2004, you have Howard Dean’s famous scream. And even before that, everybody was like, “Wow, this guy’s finally standing up for progressivism.” I mean, it seems to me that if you have a situation where the Democratic presidential candidates are limited in what they can say and how they can act, that this kind of progressive idea of, say, supporting something like the Equal Rights Amendment, you’re almost not allowed to do that. So how did this state come to be and what solutions do we have for the future?

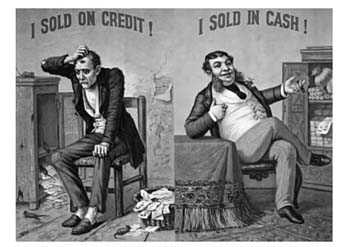

Correspondent: You start this book with a late 19th century image of the fat and prosperous man who sold in cash and the skinny man who sold on credit. I think that more than a century later, it’s safe to say that those roles have now been flip-flopped. You also write, “In the era of the CMO, the smart bank could be like the Skinny Man, its vaults nearly empty, with a pile of IOUs in a nearby basket.” I have to ask you, Louis. You are the debt man. Why were so many people willing to place their faith in the supernatural qualities of the collateralized mortgage obligation? Your book describes a Freddie Mac ad that appeared in a 1984 issue of the American Bankers Association Journal which contained magical gnomes. And they frightened me when I saw that picture.

Correspondent: You start this book with a late 19th century image of the fat and prosperous man who sold in cash and the skinny man who sold on credit. I think that more than a century later, it’s safe to say that those roles have now been flip-flopped. You also write, “In the era of the CMO, the smart bank could be like the Skinny Man, its vaults nearly empty, with a pile of IOUs in a nearby basket.” I have to ask you, Louis. You are the debt man. Why were so many people willing to place their faith in the supernatural qualities of the collateralized mortgage obligation? Your book describes a Freddie Mac ad that appeared in a 1984 issue of the American Bankers Association Journal which contained magical gnomes. And they frightened me when I saw that picture. Hyman: Exactly. So you need to understand that it used to be that it was very difficult to get loans in America of any kind. And that’s why I start the book off with that picture. Because the picture of the Skinny Man, who is nervous and afraid because he had lent on credit to his customers in his store. It was a picture that would be hung in a 19th century store. And the reason I start with that is because I think more than a graph, we are all besieged by numbers these days. More than a graph, it gets at the different mentality, the different practice of lending in the 19th century. That lending was something that was not profitable. It was something that in terms of cash loans wasn’t even legal. And yet today it’s the center of our capitalism. So how did that transformation happen?

Hyman: Exactly. So you need to understand that it used to be that it was very difficult to get loans in America of any kind. And that’s why I start the book off with that picture. Because the picture of the Skinny Man, who is nervous and afraid because he had lent on credit to his customers in his store. It was a picture that would be hung in a 19th century store. And the reason I start with that is because I think more than a graph, we are all besieged by numbers these days. More than a graph, it gets at the different mentality, the different practice of lending in the 19th century. That lending was something that was not profitable. It was something that in terms of cash loans wasn’t even legal. And yet today it’s the center of our capitalism. So how did that transformation happen?  Hyman: People forget. They forgive. And they think that it would be different this time. Because they were tradeable in the secondary market, which the ones in the 1920s were not. They were born toxic almost in the 1920s. But they thought, “Well, these will be fine. They’ll be like FHA loans.” Which had worked for several generations. And actually they worked fine. The securitization worked fine for a long time. From the mid-1970s on for about thirty years. They worked fine.

Hyman: People forget. They forgive. And they think that it would be different this time. Because they were tradeable in the secondary market, which the ones in the 1920s were not. They were born toxic almost in the 1920s. But they thought, “Well, these will be fine. They’ll be like FHA loans.” Which had worked for several generations. And actually they worked fine. The securitization worked fine for a long time. From the mid-1970s on for about thirty years. They worked fine.