(This is the thirty-first entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: A High Wind in Jamaica.)

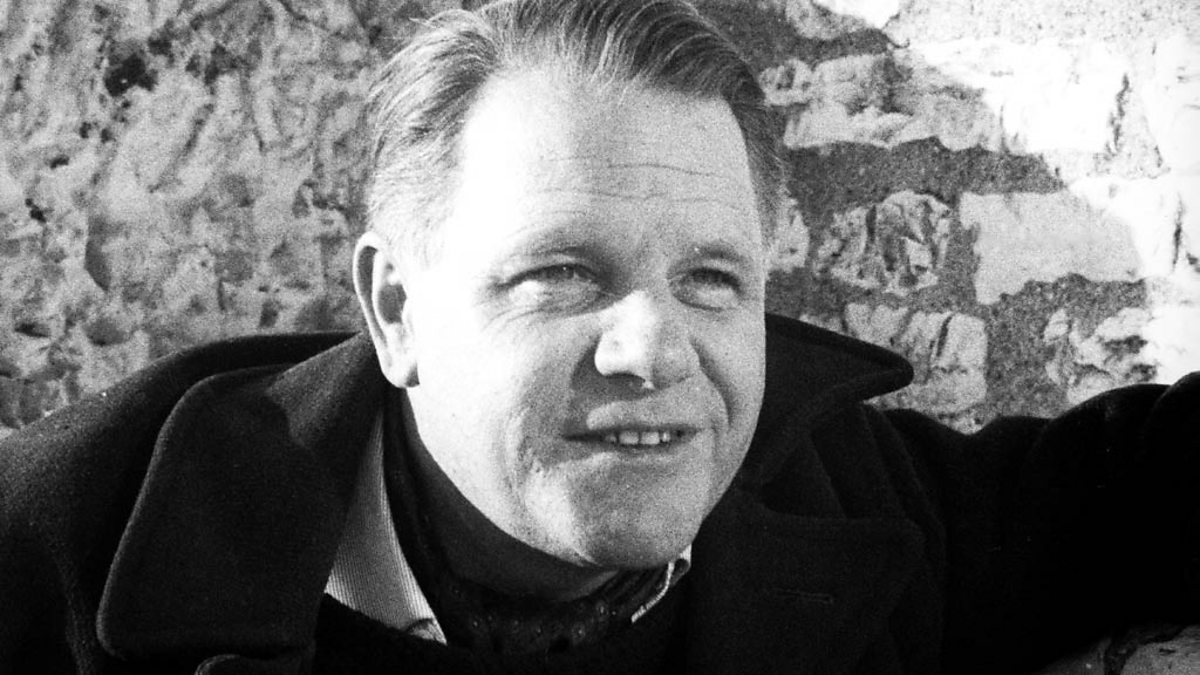

In a previous life, when talent and bonhomie mattered more than sad resentful ciphers dedicating their wasteful energies to demolishing rivals on social media, I had the great privilege to interview authors. I once made a northeastern trek by train to talk with a literary titan — a formidable essayist, a first-rate fiction writer, and a mischievous wit with a bright high voice who is still blessedly alive and who remains quite undersung today. After I pressed the square STOP button on my bulky black recording unit, we got to gabbing for two more hours off-tape — an act of generosity that stunned my companion and me. The author surprised us by confessing that she had played the then-in-vogue Angry Birds and we discussed the literary classics that young people read (or, more frequently, neglect). She was very likely picking our unweaned and less wiser brains in that pre-Trumpian epoch when, even then, declining erudition was a growing pestilence, as it wasn’t all too often that she had the company of young strangers at her long refectory table, which was punctuated by a plate of store-bought cookies that no one touched. The first name that this author mentioned was Lawrence Durrell.

“Does anyone even read him anymore?” she asked.

Neither my companion nor I had read a single word of this almighty author at the time. As I was to learn only in the last few months, I missed the teenage ritual of diving into Durrell by about five to ten years. Justine, Balthazar, Mountolive, and Clea. These were the four volumes read by an impressionable generation just before me. My older literary friends describe soaking up Durrell’s words with wide and voracious eyes around seventeen — just before they joined the less exclusive liturgical practice of tossing their tasseled caps into the heavens preceding the uncertain foray into higher education and the newfound duty of negotiating injurious capitalism (clearly not redeemable by taxation these days, contrary to sentiments expressed by the novelist Pursewarden in Mountolive).

Neither my companion nor I had read a single word of this almighty author at the time. As I was to learn only in the last few months, I missed the teenage ritual of diving into Durrell by about five to ten years. Justine, Balthazar, Mountolive, and Clea. These were the four volumes read by an impressionable generation just before me. My older literary friends describe soaking up Durrell’s words with wide and voracious eyes around seventeen — just before they joined the less exclusive liturgical practice of tossing their tasseled caps into the heavens preceding the uncertain foray into higher education and the newfound duty of negotiating injurious capitalism (clearly not redeemable by taxation these days, contrary to sentiments expressed by the novelist Pursewarden in Mountolive).

Now that I have finally read the mighty quartet — with its gorgeous sentences, its exotic vernacular (which caused even a rhapsodic word nut and undefeated Wordle regular like me to make repeat trips to the dictionary), its bold meditations on “modern love” (a term of art regrettably coarsened by the New York Times‘s often vapid essays and an even more vacuous television offshoot) and intertextuality (most notably, Balthazar‘s Interlineal), its vast tapestry of unreliable narrators and colorful characters (many marked by disease and disfigurement and, most tellingly, the absence of eyes; the number of one-eyed characters throughout the Quartet greatly overshadows the sum of spastic dancers you’ll find in any Brooklyn nightclub on a Saturday night), and the hypnotic and baleful city at the center of all these proceedings — I am frankly kicking myself for not getting around to it much earlier. My reading experience was a true coup de foudre.

This tetralogy is clearly one of the 20th century’s greatest literary achievements. I suspect, as I crest closer to the age of fifty and reckon with surprising strains of unsummoned maturity that have often bemused me, that this was the last possible moment of my life in which I could have supped upon Durrell with an eager appetite. There are only a handful of living writers whose command of the written word beckons you to slow down and imbibe the text ever so delicately — much like a pied crested cuckoo leisurely supping on drops of rain water. Of Alexandria itself, we learn of warm winds that strike against the cheek as “soft as the brush of a fox” from an enchanting near-phantom city “whose pearly skies are broken in spring only by the white stalks of the minarets and the flocks of pigeons turning in clouds of silver and amethyst; whose veridian and black marble habour-water reflects the snouts of foreign men-of-war turning through their slow arcs.” Even if one is blind and cannot see the Nile’s adjacent estuary, there is eldritch life within the “gloomy subterranean library with its pools of shadow and light,” where “fingers [move] like ants across the perforated surfaces of books engraved for them by a machine.”

Shallow word-wasters have abseiled down the other side of once robust parapets with evermore ubiquity these days, emboldened by the narcotic allure of likes and follows rather than the purer and more rewarding journey set by the instinctive tempo of their distinct voices. But Durrell (whose name rhymes with “squirrel” and not the inexact “laurel,” as I have unknowingly mispronounced for decades) is very much on the level. Given the astronomical prices of his non-Alexandria volumes online — despite a well-received four season television series on the Durrell family in recent years and an enthusiastic nonprofit society sustaining a cheery and active Twitter presence — it appears likely that Lawrence Durrell is fated to be forgotten. All writers, of course, have their time and eventually fade into the sunset. Very few of today’s readers speak of Naipaul, Ford Maddox Ford, John Dos Passos, or even Anthony Burgess anymore. For some of these plodding stampeders now collecting well-earned dust in used bookstores from here to Gehenna, there is sturdy raison that only a handful of graying hangers-on will dispute. (Besides, what kind of giddy and obsessive bastard reckons with ancient canons when one is regularly unsettled by the cannonades of apocalyptic headlines and the high probability of a third world war? An increasingly shrinking number these days, easily a hundredfold more minuscule than the combined tally of all who still collect vinyl and Beanie Babies.) But in Durrell’s case, this feels like a notable criminal oversight. Particularly since crossing the four book Rubicon was, not so long ago, a vital rite for any stripling with unquenchable curiosity.

It all starts with an unnamed Irishman (whose name is revealed to be Darley a few books later) in exile on an island with a child, recalling his passionate affair with a woman named Justine. Justine is married to a distinguished Copt diplomat named Nessim. Before that, Justine had been married to a tyrannical French national and that life has been captured in a book called Moeurs written by some guy named Jacob Arnauti. Intertexuality and the struggle to make sense of ineffable feelings through words (or even the words from another committed and capricious chronicler) is very much a Durrell motif. Darley has abandoned a devoted and far too patient dancer named Melissa for the sake of this seemingly distinguished affair. There is also a mysterious painter named Clea, who smartly tells Darley, “Love is horribly stable, and each of us is only allotted a certain portion of it, a ration. It is capable of appearing in an infinity of forms and attaching itself to an infinity of people.”

But what if the “love” that Darley feels has not been reciprocated in the way that he has believed? Durrell’s second volume, Balthazar, calls into question all the events of the first volume, with Balthazar himself (a mystical Jewish doctor who is involved with the Cabal) arriving by sea with an annotated version of Darley’s manuscript. The third volume, Mountolive, not only expands these angsty escapades to the vaster canvas of surprising espionage developments that often crackle with the griping momentum of a John le Carre novel, but reveals the tableau from the third-person vantage point of the titular diplomat, where we not only learn that Nessim has an unhinged brother named Narouz, but that Mountolive himself is mad about their mother, Leila. Finally, in Clea, we return back to the narrator Darley, five years after the Rashomon-like events of the first three volumes. The Second World War now unsettles the city. And the characters we have been rapturously following are still trying to make sense of the events that have happened, but what living now encompasses. Which is not all that removed from today’s practice of doomscrolling, dodging new variants, and submitting one’s deltoid for yet anther booster shot. As Darley himself puts it:

I am hunting for metaphors which mighty convey something of the piercing happiness too seldom granted to those who love; but words, which were first invented against despair, are too crude to mirror the properties of something so profoundly at peace with itself, at one with itself. Words are the mirrors of our discontents merely; they contain all the huge unhatched eggs of the world’s sorrows.

Amazingly, Durrell wrote Clea in four weeks.

It may seem from my description that Durrell was merely a relentless brooder, but he was often quite witty with his pen. Biographies from Ian MacNiven and Gordon Bowker both depict Durrell’s obsession with the great P.G. Wodehouse. And Durrell fueled these comic energies in humorous stories about a diplomat named Antrobus. While the tableau of Scobie cross-dressing as Dolly Varten in Balthazar possesses the dowdy feel of an entry in the Carry On film franchise, Sir Louis’s eccentricities in Mountolive could almost be interposed to an Evelyn Waugh novel:

Within the last year, and on the eve of retirement, the Ambassador had begun to drink rather too heavily — though never quite reaching the borders of incoherence. In the same period a new and somewhat surprising tic had developed. Enlivened by one cocktail too many he had formed the habit of uttering a low continuous humming noise at receptions which had earned him a rather questionable notoriety. But he himself had been unaware of this habit, and indeed at first indignantly denied its existence. He found to his surprise that he was in the habit of humming, over and over again, in basso profundo, a passage from the Dead March in Saul. It summed up, appropriately enough, a lifetime of acute boredom spent in the company of friendless officials and empty dignitaries.

One reason why Durrell’s voice is so distinct on the page — and why it has been so inimitable since (only Malcolm Bradbury and Roger Angell have attempted Durrell parodies, with unsustainable and ineffectual results) — is because he needed a fellow outlier (specifically, Henry Miller) and a commitment to impropriety and originality to get there. Indeed, as Durrell himself observed in a January 12, 1972 appearance at UCLA, his febrile dilettantism was his lodestar:

But it seems that every writer need a kind of placental relationship with another writer to approve of him and to help him. To reassure him. And it seems very curious how they come up in doubles in such very dissimilar people. I’m very frequently asked, “How could a writer like you admire Miller? And what on earth could he see in you?” The second question is difficult, I know. But a friendship is not qualified by the actual material one produces. And in our case, what we had in common was an unprofessional attitude to literature. In other words, neither of us were really interested in literature. Nor was Anais Nin. We were interested in other things. That is to say that we were not professional litterateurs. And we didn’t think professionally about writing. Writing, for us, was a kind of windscreen wiper which might help us to look ourselves in the eye a little more clearly. To liberate ourselves or to realize ourselves. In other words, our occupation was not literary, but philosophic really.

The journalist Peter Pomerantsev has suggested that Durrell only appeals to “the ‘cross-patriates,’ the hyphenated.” And he may very well be right. As a writer, audio producer, journalist, theatre producer, radio dramatist, sound designer, performer, voiceover man, TikTok microinfluencer (this still puzzles me), and (just weeks ago) soundtrack composer, it’s becoming increasingly harder these days to find people who aren’t so singular and unadventurous in their passions and interests. As Cormac McCarthy has said, “Of all the subjects I’m interested in, it would be extremely difficult to find one I wasn’t. Writing is way, way down at the bottom of the list.” Those of us who find joie de vivre in living as widely and as fulsomely as we can are increasingly becoming exiles like Darley.

It’s also difficult to fathom the lion’s share of today’s emerging writers being driven by the same impetus. One’s individuality is now drowned out by the unceasing firth of social media’s brackish tide, its morass of groupthink. The urge to please, to install one’s self as some influential pinnacle who plays it safe, is diametrically opposed to the noble pairing of future artists who can provide mutual succor, possibly shaking the very foundations of an increasingly stodgy medium that rewards uninventive bougie hokum and shameless mimesis. Inimical idiocrats with such stultifying surnames as Athitakis, Ulin, Kellogg, Kachka, Kreizman, Miller, Grady, Romano, Freeman, and Schaub regularly stump for what Durrell identified (through his novelist character Pursehaven) as “the ancient tinned salad of the subsidised novel.” All of them, unlike Durrell, will scarcely be recalled by anyone fifteen years after they pass. They will live out their dull and unadventurous lives and take out their parasitic resentiment on true originals with pablumatic “hot takes” that are largely mercantile and self-serving. Having abdicated their sense of humor sometime in their thirties or forties, and expressing little more than a perfunctory interest in other things, these egregious weasels continue to wage war on any dazzling lights casting a lambent heat upon their cold and cozy conformity. And contemporary literature is lesser for it.

So it becomes increasingly urgent these days to not tuck true talents like Durrell into the granules of forgotten history. Literary achievement is consummated by puckish punks who stand against the boring norms, by young writers who pay close attention to the dazzling output of all the eclectic outliers who presaged them and who summon the instinctive effrontery to pick a crucial and principled fight in the mystifying battles against misfits.

Next Up: Edith Wharton, The House of Mirth!