(This is the twentieth entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: The Face of Battle.)

Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love (pictured above) is one of my favorite paintings of the 16th century, in large part because its unquestionable beauty is matched by its bountiful and alluring enigma. We see two versions of love at opposing ends of a fountain — one nearly naked without apology, but still partially clad in a windswept dark salmon pink robe and holding an urn of smoke as she languorously (and rebelliously?) leans on the edge of a fountain; meanwhile the other Love sits in a flowing white gown on the other end, decidedly more dignified, with concealed legs that are somehow stronger and more illustrious than her counterpart, and disguising a bowl that, much like the Kiss Me Deadly box or the Pulp Fiction suitcase, could contain anything.

We know that the Two Loves are meant to coexist because Titian is sly enough to imbue his masterpiece with a sartorial yin-yang. Profane Love matches Sacred with a coiled white cloth twisting around her waist and slipping down her left leg, while Sacred has been tinctured by Profane’s pink with the flowing sleeve on her right arm and the small slipper on her left foot. Meanwhile, Cupid serves as an oblivious and possibly mercenary middleman, his arm and his eyes deeply immersed in the water and seemingly unconcerned with the Two Loves. We see that the backdrops behind both Loves are promisingly bucolic, with happy rabbits suggesting prolific promiscuity and studly horsemen riding their steeds with forelegs in the air, undoubtedly presaging the stertorous activity to commence sometime around the third date.

Sacred’s backdrop involves a castle situated on higher ground, whereas Profane’s is a wider valley with a village, a tableau that gives one more freedom to roam. The equine motif carries further on Sacred’s side with a horse prancing from Sacred to Profane in the marble etching just in front of the fountain, while Profane’s side features equally ripe rapacity, a near Fifty Shades of Grey moment where a muscled Adonis lusts over a plump bottom, hopefully with consensual limits and safewords agreed upon in advance. Titian’s telling takeaway is that you have to accept both the sublime and the salacious when you’re in love: the noble respect and vibrant valor that you unfurl upon your better half with such gestures as smoothing a strand of hair from the face along with the ribald hunger for someone who is simultaneously desirable and who could very well inspire you to stock up on entirely unanticipated items that produce rather pleasurable vibrations.

There are few works of art that are so dedicated to such a dichotomous depiction of something we all long for. And Titian’s painting endures five centuries later because this Italian master was so committed to minute details that, rather incredibly, remain quite universal about the human condition.

But what the hell does it all mean? We can peer into the canvas for hours, becoming intoxicated by Titian’s fascinating ambiguities. But might there be more helpful semiotics to better grasp what’s going on? Until I read Panofsky’s Studies in Iconology, I truly had no clue that Titian had been influenced by Bembo’s Asolani or that the Two Loves were a riff on Cesare Ripa’s notion of Eternal Bliss and Transient Bliss, which was one of many efforts by the Neoplatonic movement to wrestle with a human state that occupied two modes of shared existence. Panofsky also helpfully points out that Cupid’s stirring of the fountain water was a representation of love as “a principle of cosmic ‘mixture,’ act[ing] as an intermediary between heaven and earth” and that the fountain can also be looked upon as a revived sarcophagus, meaning that we are also looking at life and love springing from a coffin. And this history added an additional context for me to expand my own quasi-smartypants, recklessly dilletantish, and exuberantly instinctive appreciation of Titian. In investigating iconology, I recalled my 2016 journey into The Golden Bough (ML NF #90), in which Frazer helpfully pointed to the symbolic commonality of myths and rituals throughout multiple cultures and across human history, and, as I examined how various symbolic figures morphed over time, I became quite obsessed with Father Time’s many likenesses (quite usefully unpacked by Waggish‘s David Auerbach).

Any art history student inevitably brushes up against the wise and influential yet somewhat convoluted views of Erwin Panofsky. Depending upon the degree to which the prof resembles Joseph Mengele in his teaching style, there is usually a pedagogical hazing in which the student is presented with “iconology” and “iconography.” The student winces at both words, nearly similar in look and sound, and wonders if the distinction might be better understood after several bong hits and unwise dives into late night snacks, followed by desperate texts to fellow young scholars that usually culminate in more debauchery which strays from understanding the text. Well, I’m going to do my best to explicate the difference right now.

The best way to nail down what iconography entails is to think of a painting purely in terms of its visuals and what each of these elements means. Some obvious examples of iconography in action is the considerable classroom time devoted to interpreting the green light at the end of The Great Gatsby or the endless possibilities contained within the Mona Lisa‘s smile. It is, in short, being that vociferous museum enthusiast pointing at bowls and halos buried in oil and doing his best to impress with his alternately entertaining and infuriating interpretations. All this is, of course, fair game. But Panofsky is calling for us to think bigger and do better.

Enter iconology, which is more specifically concerned with the context of this symbolism and the precise technical circumstances and historical influences that created it. Let me illustrate the differences between iconography and iconology using Captain James T. Kirk from Star Trek.

![]()

Here are the details everyone knows about Kirk. He is married to his ship. He is a swashbuckling adventurer who gets into numerous fights and is frequently seen in a torn shirt. He is also a nomadic philanderer, known to swipe right and hookup with nearly every alien he encounters. (In the episode “Wink of an Eye,” there is a moment that somehow avoided the censors in which Kirk was seen putting on his boots while Deela brushes her hair.) This is the iconography of Kirk that everyone recognizes.

But when we begin to examine the origins of these underlying iconographic qualities, we begin to see that there is a great deal more than a role popularized by William Shatner through booming vocal delivery, spastic gestures, and an unusual Canadian hubris. When Gene Roddenberry created Star Trek, he perceived Captain Kirk as “Horatio Hornblower in Space.” We know that C.S. Forester, author of the Hornblower novels, was inspired by Admiral Lord Nelson and a number of heroic British authors who fought during the Napoleonic Wars. According to Bryan Perrett’s The Real Hornblower, Forester read three volumes of The Naval Chronicle over and over. But Forester eventually hit upon a trope that he identified as the Man Alone — a solitary individual who relies exclusively on his own resources to solve problems and who carries out his swashbuckling, but who is wedded to this predicament.

Perhaps because the free love movement of the 1960s made the expression of sexuality more open, Captain Kirk was both a Man Alone and a prolific philanderer. But Kirk was fundamentally married to his ship, the Enterprise. In an essay collected in Star Trek as Myth, John Shelton Lawrence ties this all into a classic American monomyth, suggesting that Kirk also represented

…sexual renunciation, a norm that reflects some distinctly religious aversions to intimacy. The protagonist in some mythical sagas must renounce previous sexual ties for the sake of their trials. They must avoid entanglements and temptations that inevitably arise from satyrs, sirens, or Loreleis in the course of their travels…The protagonist may encounter sexual temptation symbolizing ‘that pushing, self-protective, malodorous, carnivorous, lecherous fever which is the very nature of the organic cell,’ as Campbell points out. Yet the ‘ultimate adventure’ is the ‘mystical marriage…of the triumphant hero-soul with the Queen Goddess” of knowledge.

All of a sudden, Captain Kirk has become a lot more interesting! And moments such as Kirk eating the apple in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan suddenly make more sense beyond the belabored Project Genesis metaphor. We now see how Roddenberry’s idea of a nomad philanderer and Forester’s notion of the Man Alone actually takes us to a common theme of marriage with the Queen Goddess of the World. One could very well dive into the Kirk/Hornblower archetype at length. But thanks to iconology, we now have enough information here to launch a thoughtful discussion — ideally with each of the participants offering vivacious impersonations of William Shatner — with the assembled brainiacs discussing why the “ultimate adventure” continues to crop up in various cultures and how Star Trek itself was a prominent popularizer of this idea.

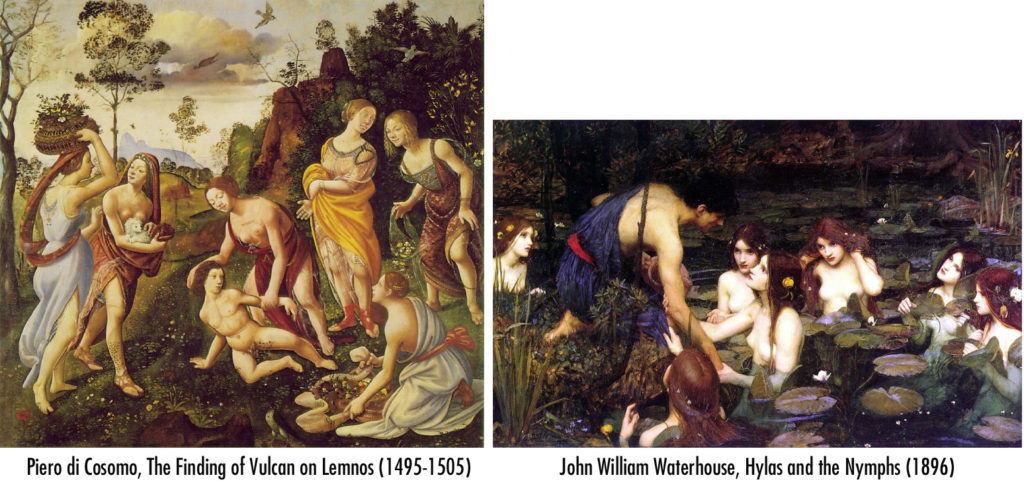

Now that we know what iconology is, we can use it — much as Panofsky does in Studies in Iconology — to understand why Piero di Cosimo was wilder and more imaginative than many of his peers. (And for more on this neglected painter, who was so original that he even inspired a poem from Auden, I recommend Peter Schjeldahl’s 2015 New Yorker essay.) Panofsky points out how Piero’s The Finding of Vulcan on Lemnos (pictured above) differs in the way that it portrays the Hylas myth, whereby Hylas went down to the river Ascunius to fetch some water and was ensnared by the naiads who fell in love with his beauty. (I’ve juxtaposed John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs with Piero so that you can see the differences. For my money, Piero edges out Waterhouse’s blunter version of the tale. But I also chose the Waterhouse painting to protest the Manchester Art Gallery’s passive-aggressive censorship from last year. You can click on the above image to see a larger version of both paintings.) For one thing, Piero’s painting features no vase or vessel. There is also no water or river. The naiads are not seductive charmers at all, but more in the Mean Girls camp. And Hylas himself is quite helpless. (The naiad patting Hylas on the head is almost condescending, which adds a macabre wit to this landlocked riff.) Piero is almost the #metoo version of Hylas to Waterhouse’s more straightforward patriarchal approach. And it’s largely because not only did Piero have a beautifully warped imagination, but he was relying, like many Renaissance painters, upon post-classical commentaries rather than the direct source of the myths themselves. And we are able to see how a slight shift in an artist’s inspiration can produce a sui generis work of art.

Panofsky is on less firm footing when he attempts to apply iconology to sculptures and architecture. His attempts to ramrod Michelangelo into the Neoplatonic school were unpersuasive to me. In analyzing the rough outlines of a monkey just behind two of Michelangelo’s Slaves (the “dying” and the “rebellious” ones) in the Louvre, Panofsky rather simplistically ropes the two slaves into a subhuman class and then attempts to suggest that Ficino’s concept of the Lower Soul — which is a quite sophisticated concept — represents the interpretive smoking gun. This demonstrates the double-edged sword of iconology. It may provide you a highly specific framework for which to reconsider a great work of art, but it can be just as clumsily mistaken for the absolute truth as any lumbering ideology.

Then again, unless you’re an insufferable narcissist who needs to be constantly reminded how “right” you are, it’s never any fun to discuss art and ideas with people who you completely agree with. Panofsky’s impact on art analysis reminds us that iconology is one method of identifying the nitty-gritty and arguing about it profusely and jocularly for hours, if not decades or centuries.