BORN READING

by Jason Boog

Touchstone, 336 pages

On November 27, 1960, only a few months after Green Eggs and Ham was published, Dr. Seuss called for a movement more modest than the Ham and Eggs pension drive. Seuss argued that “children’s reading and children’s thinking are the rock bottom base upon which this country will rise. Or not rise.” He was deeply concerned about the increasing junk being published under the guise of juvenile fiction and he rightly pointed out how children were “eagerly welcoming the good writers who talk, not down to them as kiddies, but talk to them clearly and honestly as equals.” (In the same manifesto, the good Theodore Geisel also promulgated the fanciful claim that he was “mayor of La Jolla,” but this hardly detracts from his salient points.)

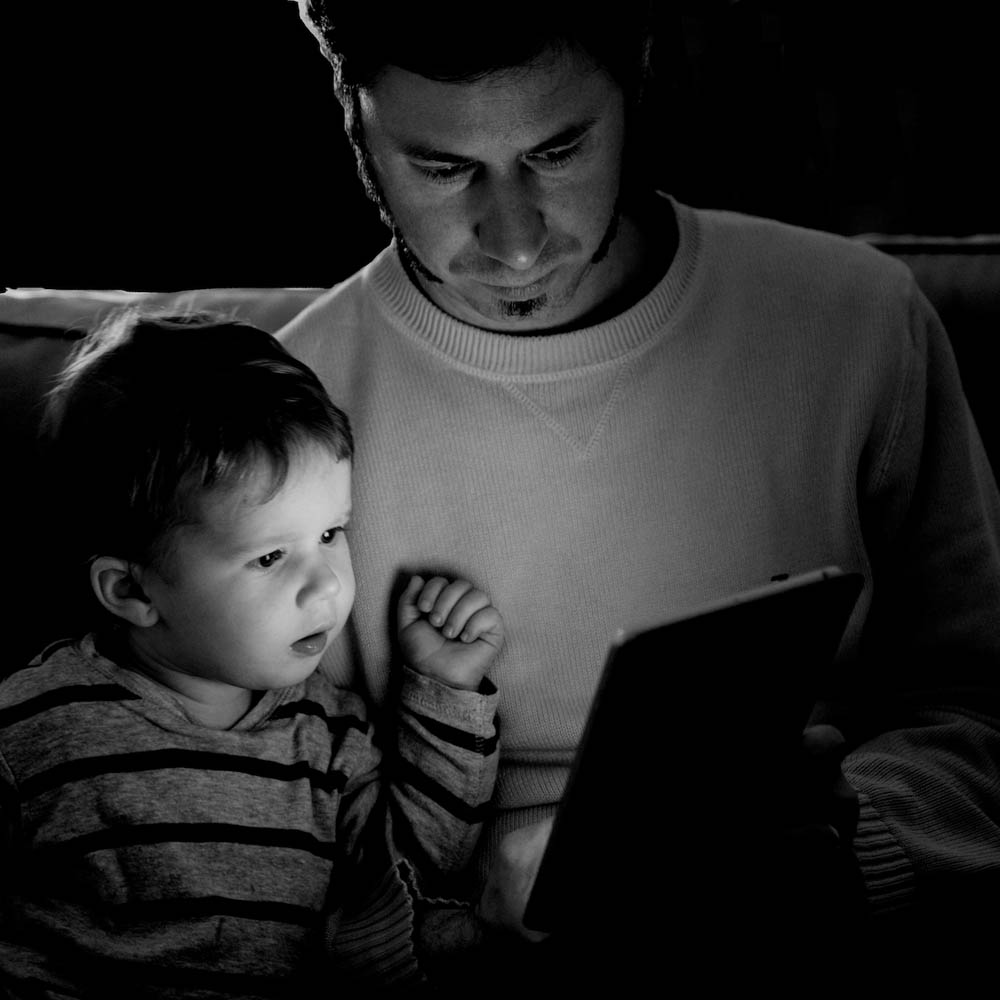

Eight years before this, Seuss had written another essay on how people laughed less as they grew older, with the fun “getting hemmed in by a world of regulations.” Yet even Seuss’s imagination could not have foreseen our world of digital devices, with the horrifying 2011 video of a one-year-old baby flipping through a physical magazine, her hand squeezing on fixed text and hoping to push it across a malleable vortex, and with her little fingers, yearning for any toy, trying to flip a photo because she believes that the page is a tablet. The parent, with the toxic cruise control bravado of a privileged Google Bus commuter who refuses to see the world beyond his soy vanilla latte and gluten-free muffin, offers the smug, self-congratulatory, and ire-inducing caption, “For my 1 year old daughter, a magazine is an iPad that does not work. It will remain so for her whole life. Steve Jobs has coded a part of her OS.”

With tablets and smartphones increasingly replacing television as the screen-based babysitter of choice for the overtaxed parent, we have very little knowledge on what this will mean for the next generation of readers and thinkers. With Common Core literary standards introducing preposterously dogmatic regulations (“Retell stories, including key details, and demonstrate understanding of their central message or lesson” reads one such farcical instruction) into classrooms with the same blindly faithful haste as the digital devices, any reliable advocate for imagination and salutary tomfoolery is left to wonder if we are preparing a generation that will surrender its wonder and humor earlier, without the pull of palpable paper to trigger some potential to raise this broken nation.

As a childless man often on call for friends with kids who demand yet another vivacious in-home performance of my free-form vaudeville show, I didn’t realize how much I cared about any of this until I read Jason Boog’s thoughtful Born Reading. (I also recommend Boog’s recent appearance on Colin Marshall’s excellent podcast, Notebooks on Cities and Culture, which discusses many of the issues in the book.) Boog harbors no illusion that we can go back to the analog ways, but he has gone out of his way to document his reading experiments with his daughter, Olive. He recognizes the overcrowded field of parenting handbooks, pointing out in the book’s early pages that he won’t be offended if the time-challenged parent doesn’t read beyond the introduction. But even with the book’s self-help thrust with sections devoted to a “Born Reading Playbook,” Boog’s volume is worth considering as a whole. Boog is candid enough to cop to enjoying Don Ho’s kitschy ditty “Tiny Bubbles,” but he also recognizes the nefarious ways that diabolical software developers sneak hypnotic advertisements into apps that are ostensibly intended to “educate.” We often forget this Faustian bargain, if we even bother to remember it at all.

The smartphone is only seven years old and the iPad, at the age of four, is only a year away from entering kindergarten. How are these new and ubiquitous technological tools shaping our real and decidedly more irreplaceable children? Boog rightfully points out, through the statements of Lisa Guernsey, that the conversations that adults have with their children before the age of two are more valuable than any interactive bauble. If a parent is too beleaguered, perhaps she can find a bedtime solution with the physical book, with its promise of enticing worlds beyond the real, its firm hold requiring neither wi-fi nor batteries, and its manifold possibilities for acting out stories. Last year, in a well-publicized report, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that parents discourage media exposure for children under the age of two. The AAP also suggested that children over that age should never spend more than two hours in front of a screen. Yet there remains the ineluctable lure of the digital babysitter. Put your kid in front of a screen playing mindless entertainment and, voila, even you too can get a few household chores done! But because the new screens are portable and more regularly used, even bright children such as Olive are tempted to imitate their parents, often resulting in workaround mimicry to postpone the inevitable moment when real digital devices will be as close to them as Barbie dolls and Matchbox cars:

Even before she turned two years old, Olive would mimic my cell phone cradle with various phone-shaped objects. I designed a pretend computer out of a cardboard box and an abandoned computer mouse, and Olive would dutifully plug in the mouse and press imaginary buttons on the box just like daddy.

Boog is extremely diligent in limiting his daughter’s digital usage, yet smartphones and tablets also offer undeniable value in summoning an immediate response to a child’s question. Boog describes calling up several images of Brahams after Olive asks what the famous composer looks like. In the analog days, parents offered approximate and often quite wrong answers to a child’s endless string of whys. But now that the highly specific answer has become commonplace thanks to Google, there remains the more troubling problem of how to encourage imagination and curiosity when nobody can be leisurely wrong anymore. Maybe the key for healthy digital implementation among toddlers resides in only using digital devices to promote curiosity. It is certainly an ethos that Boog subscribes to:

Reading for discovery can change the course of your child’s life. You can help him or her maintain a natural curiosity throughout school. This precious flame of scientific wonder can be snuffed so easily. Don’t let your child lose that sense of wonder. Follow up science books and apps with zoo visits or natural science museum trips. Make sure that part of your home library is dedicated to science, gross or scary as it may be.

Providing a toddler with limitless words and endless options for discovery can mean the difference between a child armed the tools to succeed and one who gives up in a tougher world of standardized education. Betty Hart and Todd Risley conducted a famous study revealing a thirty million word gap between low and high income kids. This disparity revealed lasting effects later in life. But with enough active parental participation, it is possible to make a book stick. Boog describes repeatedly reading Dick and Jane and Vampires to Olive, often acting out the story with gusto. The book became such a fixture that Olive demanded the book at all hours.

For cash-strapped parents who don’t have the resources to fill their child’s bedroom with books, there is also the public library. Judy Blume’s oft-quoted suggestion that children should be allowed to read whatever they want holds true even in this hallowed space, which is not merely a secular temple for books, but a place for many kids and parents to come together. If Boog’s book ends on an appropriately grim note when considering the draconian Common Core standards, very much at odds with unhindered reading and free-flowing curiosity, it is nevertheless a welcome reminder that merely asking children to regurgitate knowledge is a recipe for chaos as the gap between the rich and the poor grows to its highest level since 1928. If we want to lift our nation beyond this crippling inequality, then it is vital for us to reject any measure that prevents parents and educators from talking with children as equals. The Seussian ideal will allow the next generation to embrace and challenge knowledge rather than have facts drilled into their heads with all the delicacy of a bureaucrat fumbling around with a jackhammer.

(Image: mbeo)