Norman Rush is most recently the author of Subtle Bodies.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Author: Norman Rush

Subjects Discussed: Keeping a personal existential view of the world on one paper, utopian democracy, allusions to Ulysses in Rush’s work, Vico Cycles, the importance of the 2003 Iraq War protests (and why they have been forgotten), whether forms of liberalism have any legitimate application in the 21st century, the importance of physical space in Rush’s fiction, people who preserve language vs. people who are terrified of originality, how people express themselves, the origins of “in your wheelhouse” and “traveling fight,” comparing various drafts of a “plaid underpants” section in Subtle Bodies, carrying something in your head vs. writing it down, unsuccessful attempts to outperform geniuses, the specific cocktail chatter that led Elsa and Norman Rush to become Peace Fund co-directors in Botswana, draft resistance, amnesty, how an anti-establishment stance can you lead you into an establishment job, the virtues of insouciance, working with editor Ann Close at Knopf, invaluable oddities, personal aversions to semicolons, dialogue and punctuation, singing prose out aloud, Rush’s bygone ukelele skills, resisting the essayist and journalistic in fiction, Sherlock Holmes pastiches, being an anti-minmialist, the carefully designed reading pace of Mortals, limited word use in Botswana cable transmissions, why America is now crazier than Botswana, the three cartons of notes that Rush brought back to America, spending 15 years in the antiquarian book business, exquisitely unknown incidents in the history of the Western Left, the failure of the Socialists to come together on an antiwar platform in 1914, Rush’s stubborn focus on being an experimental writer and a poet in his early days, the anxiety of influence, measuring yourself against the impossible, the origins of Karen in “Bruns,” Patrick van Rensburg, having an indomitable vocabulary, how much Mating‘s Karen was influenced by Denoon, how Rush got to know his great literary friend Thomas Disch, being a genuine man of letters, Manhattan’s financial hostility to writers, finding creative ways to live in Brooklyn, parenthood in Subtle Bodies, connections between Nina in Subtle Bodies and Nan in “Near Pala,” ancillary subjects that propagate during writing, tales of masculine sadness throughout literature, David Foster Wallace, the limited makeup of today’s literary audience, Lena Dunham’s appreciation for Mating, comparisons between Mating and Adelle Waldman’s The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P, characters defined by reading allegiances, the manuscript as a bomb, writing down what people have on their bookshelves, the sangoma in “Official Americans,” Morel in Mortals, why Rush’s characters are seduced by or drawn to charlatans, Rush’s father, religion and theosophy, the foundational aspects of what you are, spiritualism as an unavoidable part of being American, Rush’s “Americanity,” motives for burning a passport, why optimism is essential, parallels between Subtle Bodies and the great Edgar Wright-Simon Pegg film The World’s End, ideologues and the absence of identity, nostalgia as a panacea of anxiety, turning tropes into foundations for serious art, Rex from Mortals, flailing aspirants who write for The Awl, middling educated types, fiction as a place for failed forms of the self, dummy experimentalism, sections from Mortals that were dropped, cave art, the differences between expatriates and Americans who stay home, James Wood’s observations about Ray Finch’s interpretation of Joyce’s “The Dead,” the courage to inhabit an unseemly perspective, the reading Rush did while working as an antiquarian bookseller, fiction with numbered paragraphs, Hume’s influence upon Subtle Bodies, writing a book without a sustained perspective, the Kalahari Desert, the advantages of being overwhelmed with life you are not acquainted with, describing the landscape with waning movie metaphors, young people forced into scavenging from culture, the messianic qualities of 20th century Hollywood stars, the future of narrative, balancing the personal and the political, the importance of recognizing the evils of the world and not to be a fool, people who are increasingly duped in the digital age, facing an unreadable future, the Internet and political activism, and the future of social democracy.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I was curious about this. You were showing me these series of Venn diagrams that represents your existential view. I’m amazed that you could fit this all on one paper.

Rush: Well, actually, I’d need a much larger piece of paper to get the whole thing on. This is about current feelings about the way the world is going.

Correspondent: Are they negative or positive?

Rush: I’d say they could be described as apocalyptic, but in a piecemeal way. I’m not looking for a big bang, but I think serious trouble is coming. And I’ll explain what I mean by that in describing a lack of fit between what the evolved political institutions of our advanced capitalist world, capitalist republic, can deal with and the scale of the problems that are presenting themselves autonomously, outside of anybody’s control.

Correspondent: Well, maybe one way to kickstart this is to tie in a sentiment in Mating with what is going on in Subtle Bodies. In the early Circe-like part of Mating, you have Nelson Denoon’s speech for his solar democracy, Tsau. “Everything we want in a society is what we find brought out in people and the moment of insurrection. Spontaneity! Spontaneous hierarchy!” There are exclamation marks after all of this. “Self-sacrifice! Staying awake all night! Working until we drop! Audacity! Camaraderie! The carnival behind the barricades.” Well, in Subtle Bodies, you have this compound called The Vale. It’s a sprawling place. It’s just outside Kingston. It’s the home to activists. It’s reminiscent in some ways of the Martello Tower at the very beginning of Ulysses. And, in fact, you actually compare it to the Winchester Mystery House. As a South Bay guy, I got that little reference.

Rush: Oh, you’re South Bay.

Correspondent: Yeah. So my question to you is, well, based on what you were expressing earlier, to what degree was this your way of exploring a Vico Cycle in which America is caught within a perpetual moment of insurrection?

Rush: Well, that’s very acute. This is about one of the last flashes of the revolutionary impulse to make a significant change. In this case, stopping the impending invasion of Iraq. So it’s not about making a New Society in the old sense. In the way that Denoon was talking about. But it’s about a much more reduced yet still large objective. And that is basically a negative one. But stopping something from happening.

Correspondent: Well, it’s interesting. Because that Iraq War protest in 2003 is often forgotten by many of the people, like the Occupy crowd. I mean, there were regular people who attended these series of protests. And it’s kind of been swept under the dustbin of history. Is this one of the motivations to explore this in fiction?

Rush: Absolutely. And in fact, it was in its time the largest international demonstration in history. All countries, all over the West. Not only here. And it represented a high watermark of emotion left over from the Vietnam War, which had, in the minds of oppositionists, been stopped by exactly this kind of direct action and mass protest. And, of course, well, I don’t want to give away the end of the book or remind people too much about the history of it. But yes. And that’s another thing. I think the book is working with a kind of fading historical appreciation of what the last twenty or twenty-five years have really meant.

Correspondent: Well, let me ask you something. I mean, if societal ideals — as are represented in that Nelson Denoon speech — if they are constantly replenishing themselves in this new musk of want, what is the present state of revolution? How can fiction provide an answer or encourage or empower people to commit revolution?

Rush: Well, don’t hold back from the big questions. I mean, that is the question. Every serious writer is implicitly or explicitly asking that question. What is it that I’m writing about? What does it have to do with the seemingly autonomous evolution of increasingly less propitious circumstances to make change? And the answer to that is the central and most compelling question, it seems to me, for people who write novels which incorporate serious politics and political thinking into them. The answer keeps revealing itself as you write and as things change. I mean, one of the things that seems to be happening — one reason that this is such a fascinating and, in a way, dumbfounding moment — is that the three great propositions about how we should organize the world and life — that is to say, socialism, followed by its variants, social democracy, followed by neoliberalism — have all in their own ways collapsed and don’t exist as real options anymore. They carry on their shells. There’s a shell of socialism existing in pockets and enclaves around the world. There’s a kind of zombie social democracy operating mostly in Western Europe. And there’s neoliberalism, which is in a state of what you have to call a dispensational crisis. Because basic problems like inequality have not been solved. And in the meantime, coming from the outside is this continual costs in the environment of the systems we built.

Correspondent: But at the same time, Marxism has a lowercase m in Mating. So has there ever really been credence to any of these political systems? Why do we continue to gnaw at them if they are unimplementable in everyday society?

Rush: Oh sure. Actually with the ongoing collapse of socialism, the Socialist Project, one of the standard responses to that — and it’s happened in the past many times — is to take the socialist idea and incorporate it in tiny pieces. Tiny little enclaves. Make it work. Make a pilot model. Make it tiny. Make it small. That’s sort of what Denoon is up to.

Correspondent: I wanted to also talk with you about how space functions in your book. In Mating, you have this wonderful passage where Karen describes love as moving from one room or apartment to another, and each subsequent room or apartment is bigger and better. Also, we learn in Subtle Bodies that the Vale’s large space has become unwieldy, especially when you’re trying to snag some yogurt for breakfast. But what you just said about how America is compartmentalizing itself and how social democracy is doing that reminds me very much of the episode where Nina enters this closet and she hears these two men and you write, “She had gained nothing by putting herself in this predicament.” And I’m wondering if this is your wry way of suggesting that figurative space is the only space that we can trust in fiction, in life, or in politics.

Rush: That’s an interesting way to look at it. Actually, this is a case of her burning desire to know everything taking over her good judgment. And as a character, she is determined to know everything she can to relieve the unmerited suffering she sees of her husband’s milieu. So she puts her nose into everything in the place that they live.

Correspondent: In Mortals, Ray complains that “affray was one of those words that was vanishing from the language.” But in Subtle Bodies, you have Ned almost terrified with the imperfection of a pickup line such as “I stand here lonely as a turnstile.” Nina also says, “A pleasant despair of the region of the loins.” And she claims to be quoting something. But actually you can’t place the quote. So one must assume that it’s original in some sense. If your books represent in some way a history of the way that Americans express themselves, and I think we can say that they do, why do you think your characters have moved from preserving word choice — and, of course, we have the word games as well in the early days of these characters. Why have they moved from preserving language to being terrified of the original expression? I mean, why is this of interest to you? I’m curious.

Rush: I’m interested in knowing the way that people express themselves. What lasts and what doesn’t. It’s kind of a Darwinian process that has always seemed interesting to me. For example, why do we now say that something that is within your competence is “within your wheelhouse”? “In your wheelhouse.” Now the odd thing about that is, first of all, I don’t know where it started.* But it certainly has taken over every conversation. And I was unable, and Elsa too, to recall what preceded it. What did we say when were saying to someone that he was out of his field of competence? Or in it? What did we say? Not “his line of work.” No, that’s not quite right. But there is a kind of occlusion of ways of expressing states of being and possibilities that happens. And it’s happening faster now because the media are so ever present and so tightly connected to everything. It happens fast. But I ask you. What did you say before you said, “It’s not in my wheelhouse”?

Correspondent: “Not in my purview,” I guess. I don’t know. “Not in my bailiwick.”

Rush: “Purview” is not quite right. Because this has to do with competence. “Bailiwick” is closer. But anyway, ponder it. I don’t have an answer myself.

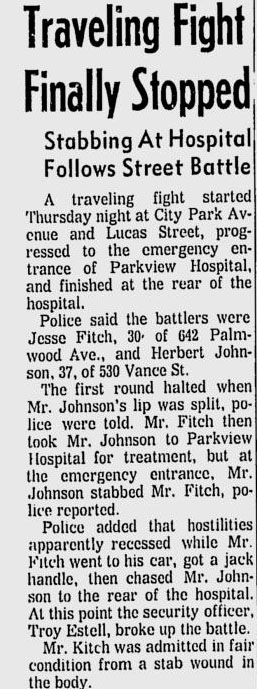

Correspondent: I mean, this leads me to wonder. There is one point in this book where you have a “traveling fight” occur. And I had never actually heard the expression “traveling fight.” And I became so obsessed with that notion of a fight moving from one place to another. And the only place I could really find it online was from a 1970s article in the Toledo Blade.

Correspondent: I mean, this leads me to wonder. There is one point in this book where you have a “traveling fight” occur. And I had never actually heard the expression “traveling fight.” And I became so obsessed with that notion of a fight moving from one place to another. And the only place I could really find it online was from a 1970s article in the Toledo Blade.

Rush: Oh my gosh. (laughs)

Correspondent: So this is interesting. They are so determined to use that term “traveling fight,” which comes from a place that they’re okay with. And yet when they’re actually trying to riff on their own phrases, they don’t want to relive the pleasure of those word games in their early lives. Also, I’m just curious about where you first heard “traveling fight.”

Rush: I can’t tell you. I know that it came up in some place along the way in my life and I’ve carried it around as a description. And then suddenly, when I needed it, there it was.

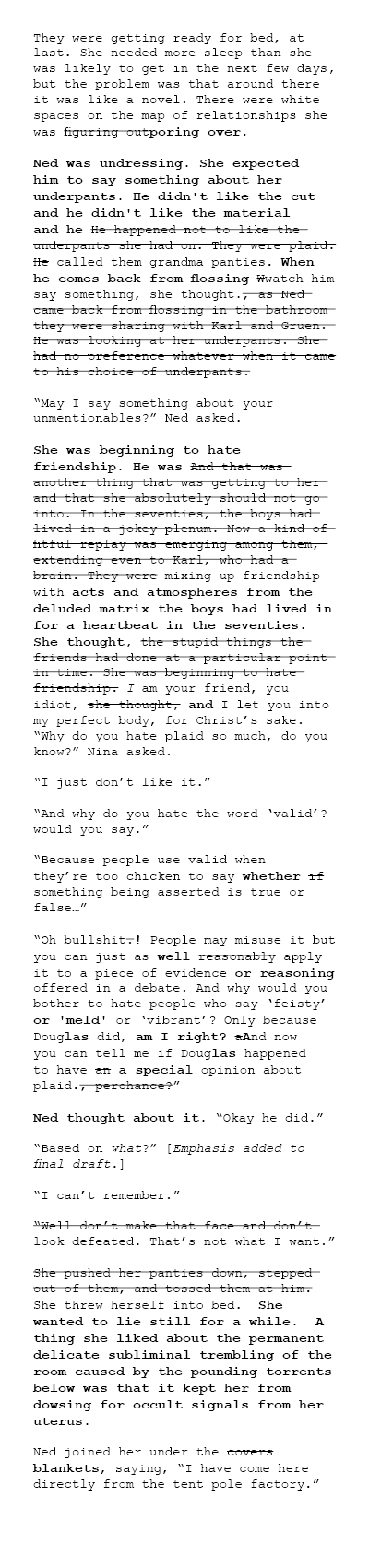

Correspondent: I found an early draft of the “plaid underpants” moment in Subtle Bodies between Ned and Nina that was published in the Los Angeles Review of Books. [NOTE: We have reconstructed Rush’s compositional revisions in the graphic at the end of this capsule.] What was curious about this is that the dialogue you have is almost the same, but there’s some interesting description in this early draft where Nina is a little more willing to judge Ned. The sentences here are “In the seventies, the boys had lived in a jokey plenum. Now a kind of fitful replay was emerging among them, extending even to Karl, who had a brain.” And in the book, you’ve added this passage where Nina describes how she likes “the permanent delicate subliminal trembling of the room.” And this leads me to ask you. To what degree are you discovering these characters in the early drafts? Has it been your practice to severely cut the degree to which your characters dwell on the past and concentrate on the present moment you are bringing to life as you’re writing it?

Rush: Yeah, that’s part of my struggle against saying everything. And you may know that the way I’ve proceeded in the past with books was to write a dossier for each individual character, so that I knew the life of the character up till that point and sometimes beyond. Just for my own reference. And that was a helpful way to proceed. But I do more of that in my head now than I used to feel I had to do on paper. But yes. I have cut down in favor of moving the action so that I can get to the next big thing.

Correspondent: Well, in terms of carrying something in your head versus writing it down, why do you think you’ve always had that packrat tendency to say everything? I mean, I’m looking here and, on the table, you have this massive and quite intriguing collection of files. So why do you think you need to say everything and you need to get it all down?

Rush: I could tell you part of the answer to the extent that I think is true, but there’s more to it. At the very heart of it, of course, there’s got to be something like fear of not having, knowing what you need when you need it. But on top of that is laid another impulse that I have when I write. And that is — it’s a kind of crazed Platonism. Because once you start a book and you set up your characters and you set up the situation and you discern the argument that is going to lie at the base of the structure, you — at least I’m speaking for myself — you have a sense that this is a copy of a perfect realization. There is a perfect working out of the plot. A perfect resolution. A perfect rhythm. Everything. There is a perfect embodiment. End point. Embodiment of the things that you set out to say. And that’s what I want to do when I set out. And this is all kind of philosophical more than I like to admit. But I’m looking for something that is like a realization like, oh say, Kurosawa gets in The Seven Samurai. When you get to the end of the uncut version, when you get to the end of that, you have fully and absolutely experienced what was intended from the very first scenes of the book to the end. Or the opera. Tosca. Or Ravel’s Boléro. At the end of it, you have had everything. It has completed itself. And I think it’s probably a self-destructive kind of impulse to be subject to. But that’s me.

Correspondent: Is it something you grabbed from Joyce?

Rush: Joyce is another example. Ulysses is. And that’s why there’s so much extra stuff in Ulysses. Because in his own not completely formed way, I see him as aiming for the same thing and achieving it in thunder.

Correspondent: But you’ve never really sought out to have Botswana reconstructed from the bricks you laid down in Mortals or Mating.

Rush: No. I thought I would never know enough really as a five year resident and student of an extremely complicated and interesting culture. I would never know enough to do that. That will be the work of some writer from that country in some time. But yeah, I was always very conscious that Botswana was a set in which I was privileged to place my people and my problems.

* — A Way With Words, a casual call-in radio program devoted to word origins and language (I have been a regular listener of this agreeable low-key show for more than a year and recommend it), proved instructive in answering this question on its March 5, 2011 installment. The term “wheelhouse” comes from baseball. According to the Dickson Baseball Dictionary, it involves swinging a bat when the ball is in your crush zone. A 2010 Daily Finance article reveals nautical origins. Its popularity in the last three years (which is on the downslide) can be traced to an episode of Glee, in which Darius Rucker told another singer that a song was not “in his wheelhouse.”

An earlier draft of the “plaid underpants” episode in Subtle Bodies was published on October 23, 2011 at the Los Angeles Review of Books. This has allowed an unanticipated glimpse into Norman Rush’s compositional approach, when we compare this earlier draft against the published version. Note how Rush’s dialogue remains mostly unmodified. But his description has undergone significant revision. Rush was kind enough to discuss this at length on the program. (Please note that Rush’s additions are in boldface. His deletions are in strikethrough.):

(Photo: Wyatt Mason, permission through Random House. Music: Kevin MacLeod, “As I Figure.”)

The Bat Segundo Show #512: Norman Rush (Download MP3)