[EDITOR’S NOTE: This is an experiment to see how blogging might be used to make sense of a rather enormous series of events. In an effort to understand why Verizon (formerly Bell Atlantic) became such a dominant force in the telecommunications industry, I am initiating the first in an open-ended series of inquiries that will be relying upon newspaper articles, public records, interviews, and any additional information I can get my hands on. My first step is to assemble a timeline with the available information. From here, I will then begin interviewing related parties to put these facts into perspective. I will be updating all of the posts as new information comes in. Please feel free to contribute any additional thoughts or leads in the comments section.]

[Subsequent installments: Part Two (August 2000). Part Three, which covers the months of September and October 2000, can be found here.]

In April 2000, Bell Atlantic was working out the details of a merger with GTE it had initiated the previous year. The deal was nearly done, awaiting FCC approval. But Bell Atlantic’s wireless communication unit needed a new name. Bell Atlantic’s wireless unit was in the process of merging with the wireless division of Vodafone AirTouch.

In April 2000, Bell Atlantic was working out the details of a merger with GTE it had initiated the previous year. The deal was nearly done, awaiting FCC approval. But Bell Atlantic’s wireless communication unit needed a new name. Bell Atlantic’s wireless unit was in the process of merging with the wireless division of Vodafone AirTouch.

Bell Atlantic had been formed in 1983. It was one of seven Baby Bells that had been formed in the aftermath of an antitrust suit filed against AT&T by the Department of Justice. Seventeen years later, with the Bell Atlantic-GTE merger set to make the new entity the largest local telephone carrier in the nation, Bell brass believed that the Bell brand was too old school, too dowdy, to fit in with the then contemporary emphasis on cutting-edge technology.

“‘We believe that we need to separate ourselves on a going-forward basis from the tradition and the limited perspective that a Bell name assigns to us,” said Bell Atlantic executive Bruce S. Gordon at the time.

The new name was Verizon, a clever case of lexical blending between “veritas” and “horizon” that was to find its way in only a few short years onto millions of cell phones, the logo attached to the apices of many skyscrapers.

Bell Atlantic had been perfecting an ambitious advertising campaign over several months that hoped to convert both Bell Atlantic wireless customers and Vodafone customers over to the new Verizon brand. Bell had employed the services of the Bozell Group, part of True North Communications. Bozell was best known at the time for its milk moustache campaign, which had featured pop culture figures such as Austin Powers and Lisa Simpson smiling with a thin strip of milk just above their upper lip. (When True North purchased Bozell in 1997, the deal made True North the sixth largest advertising company in the world. Bozell had rejected an offer from Omnicom, but True North had pledged to respect Bozell’s autonomy. This purported autonomy, however, proved incompatible with economic realities. In 2001, Bozell laid off 6% of its staff and “restructured” the creative department.)

Bell Atlantic had been perfecting an ambitious advertising campaign over several months that hoped to convert both Bell Atlantic wireless customers and Vodafone customers over to the new Verizon brand. Bell had employed the services of the Bozell Group, part of True North Communications. Bozell was best known at the time for its milk moustache campaign, which had featured pop culture figures such as Austin Powers and Lisa Simpson smiling with a thin strip of milk just above their upper lip. (When True North purchased Bozell in 1997, the deal made True North the sixth largest advertising company in the world. Bozell had rejected an offer from Omnicom, but True North had pledged to respect Bozell’s autonomy. This purported autonomy, however, proved incompatible with economic realities. In 2001, Bozell laid off 6% of its staff and “restructured” the creative department.)

The early Verizon logo featured the “V” sign in red, an attempt to mimic the Nike swoosh symbol. Was it an accident that both Vodafone and Verizon began with a V? According to New York Times reporters Stuart Elliott and Seth Schiesel, one person close to the campaign revealed that it was not.

By June, Lucent Technologies was named the primary equipment supplier to Verizon Wireless. Its stock jumped up from 3 1/4 to 59 7/8 a share on June 15, 2000. According to a letter of intent issued by Lucent, Lucent would provide network equipment to Verizon. And this relationship would then help Verizon to expand from the wireless business to high-speed Internet services, among other telecommunications possibilities. Verizon hoped that the Internet access might be one way to encourage customers to use their phones more frequently.

Two days later, on June 17, 2000, the FCC approved the Bell Atlantic-GTE merger, with the proviso that GTE would agree to spin off its Internet backbone operations. Verizon became the nation’s largest local telephony company.

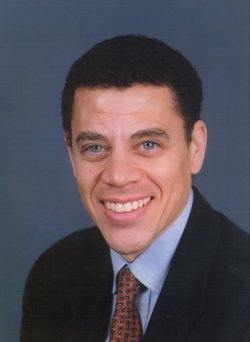

Numerous documents about the merger, including the FCC’s specified conditions, can be located here. In his statement issued after FCC approval, FCC Chairman William E. Kennard noted, “By requiring that the Internet backbone asset be spun-off and through the other merger conditions, we have preserved the fundamental incentive structure of the Act, sought to stimulate competition, and to promote more and better service offerings for consumers. For these reasons, I support this merger.” In light of recent Verizon developments that have called these “more and better service offerings” into question and Verizon’s current presence on the Internet (to say nothing about the way in which Verizon skirted around the GTE condition, described below), and notwithstanding Kennard’s competitive position as a member of the Board of Directors at Sprint Nextel, one wonders whether Kennard would still support this merger. I hope to contact Kennard and see if he might offer an answer.

However, it’s worth observing that Kennard joined the Carlyle Group as a managing director shortly after resigning from the FCC in February 2001. Carlyle purchased Verizon Hawaii for $1.65 billion. On May 22, 2004, Kennard was quoted by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin about this deal: “A big part of our plan is to return Verizon Hawaii to its roots as a local phone company, empowering local management. It’s sort of a version of ‘Back to the Future,’ if you will.” Whether this flippant comparison to a Hollywood blockbuster movie was intended to insult the journalist who posed the question is unknown. But the purchase did earn the endorsement of Verizon’s union, even if competitors and Hawaiian locals expressed dismay with the Carlyle Group’s inexperience and connections with high-level political contacts. By 2007, however, Hawaiian Telecom (the new name of the company) had experienced serious problems when BearingPoint, Inc. — the consulting firm hoping to overhaul Verizon’s systems — couldn’t make it work and was ousted in favor of Accenture, Ltd. — best known for its role in Enron. If this was a case of Back to the Future, perhaps Kennard was more accurate than he realized. Relying on outside consulting firms seemed decidedly against Kennard’s promise to “empower local management.” And indeed, earlier this year, Hawaiian Telecom’s CEO was ousted in favor of interim CEO Stephen Cooper (Kenneth Lay’s replacement), more than 100 positions were axed, and Hawaiian Telecom was still pursuing a decidedly nonlocal restructuring plan to recover from its problems.

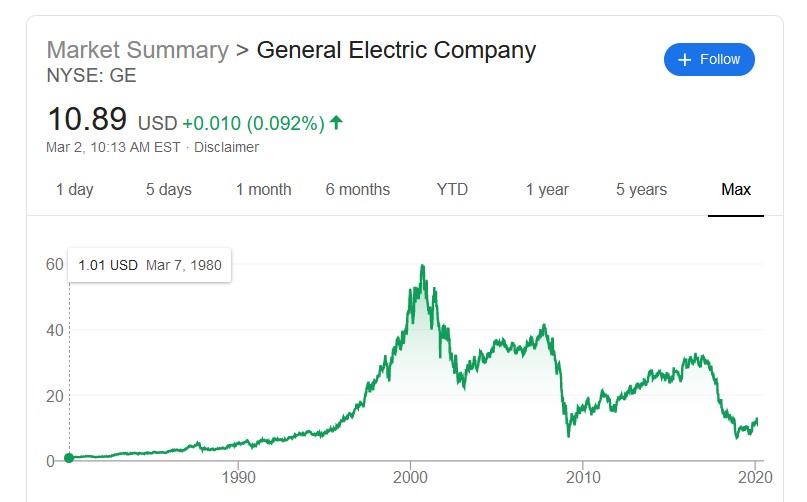

Whatever Kennard’s current feelings are for Verizon, one thing is beyond dispute. The FCC’s approval of the Bell Atlantic-GTE merger made Verizon the 2nd largest telecom company (after AT&T), permitted it to become the nation’s largest wireless operation, and made it a local telephone juggernaut. Verizon now had 63 million landlines across the country. In its first day of trading, Verizon’s stock rose $4.625 to $55 a share.

Whatever Kennard’s current feelings are for Verizon, one thing is beyond dispute. The FCC’s approval of the Bell Atlantic-GTE merger made Verizon the 2nd largest telecom company (after AT&T), permitted it to become the nation’s largest wireless operation, and made it a local telephone juggernaut. Verizon now had 63 million landlines across the country. In its first day of trading, Verizon’s stock rose $4.625 to $55 a share.

On July 4, 2000, the New York Times reported that Verizon was trying to sell off its GTE cable systems in Florida, California, and Hawaii. And to get new customers hooked, Verizon cut the prices of DSL by 20% in some parts of the United States. So while the GTE cable backbone was, per the FCC condition, technically being cut off, Verizon managed to augment its Internet services through the phone lines. Verizon, in other words, was merely swapping one type of broadband services for another. (And, indeed, that same month, the New York Times‘s Seth Schiesel would report that Verizon hoped retake ownership of Genuity, the cable network in question, in a few years.)

But it wasn’t enough for Verizon to use its legerdemain to flaunt the deal of the Bell Atlantic-GTE deal. Verizon’s legal team also felt compelled to rail against the FCC. On August 21, 2000, William Barr, the top attorney for Verizon and a man who had served as the 77th Attorney General under President George H.W. Bush, fulminated against the FCC at the Progress & Freedom Foundation’s Aspen Summit 2000 conference. In a panel titled “Perspectives on the Future of Telecom Regulation,” Barr took issue with the language of the 1996 Telecommunications Act: specifically, the manner in which the Bells were instructed to charge competitors at affordable prices in order to use their networks and discourage monopolization.

“Rather than letting the market drive competition,” said Barr, “[the] FCC has issued a host of rules to try to manage that competition and, in doing so, they have preserved a siloed approach.” This “siloed approach” also extended to the FCC’s organization itself, which was divided into separate divisions devoted to wirelsss, broadband, and telecommunications. “This comes at direct expense of intermodal communications, and it is disfiguring the telecom landscape as it evolves into the Internet landscape.”

(Eighteen months later, Barr would get his wish. At the beginning of 2002, the FCC began a campaign to reorganize its bureau. A Wireline Competition Bureau was established, containing the vestiges of the Common Carrier Bureau. In March, additional structural changes were made. The impact of these internal structural changes at the FCC, as they pertain to Verizon and the telecommunications industry, will be revisited in a future installment.)

Meanwhile, with AT&T facing both the burgeoning success of Verizon, as well as SBC Communications’s entry into the long-distance business in Texas, AT&T chairman C. Michael Armstrong was starting to get nervous. The man who had made IBM shine was now fighting for his life, working 18 hours a day, trying to figure out a way to combat flagging revenue. But what Armstrong didn’t know was that long distance plans were about to change in a very big way.

But Armstrong wasn’t going down without a fight. In July 2000, AT&T filed a federal complaint charging that Verizon was steering its customers illegally to its own long-distance service. AT&T charged that Verizon had failed to offer new phone customers a listing of long distance providers, as required by law.

Adding insult to injury on the long distance front, on July 18, 2000, a Federal appeals court ruled in a case that has serious consequences for AT&T and granted Bell Atlantic a great victory. The court, overturning rules established by the FCC, ruled that outside long distance companies (such as AT&T) using copper lines owned by a local telephone company (such as Bell Atlantic) would have to pay an increased fee to the local telephone companies. Thus, with Verizon offering long distance service through its “local” landlines, it could evade the fees. But AT&T customers would have to pay.

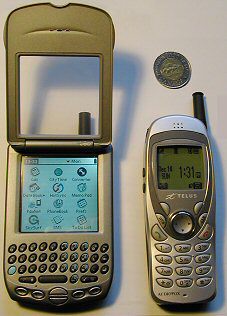

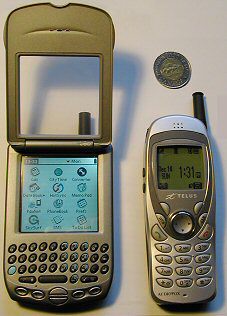

Verizon was also looking to wireless data as a source of revenue. The company had observed the success of Sprint PCS’s Wireless Web, which had been in place since November 1999. (And while Sprint was then the wireless web leader, its wireless network ranked fourth behind Verizon, SBC, and AT&T Wireless. It did not help Sprint any when it was forced the next month to abandon its attempted $115 billion merger with WorldCom.) But how could Verizon get customers to pay a monthly fee of $7 to $10, along with a per-minute fee through wireless data? Web access? With the telecoms engaged in aggressive price wars, they were looking to any possible form of additional income to obtain some leverage. And the then snail-paced wireless web access was having difficulties catching on with consumers. The wireless data revenue would come later through an unexpected source that nobody had anticipated: text messaging. But this was still sometime away.

There was some concern over the relationship between third-party vendors offering products to Verizon and Verizon’s dominance in the telecom industry. In July 2000, the New York Times reported that Audiovox, a mobile handset provider, was selling 80% of its handsets to Verizon. “When you have one customer that controls 80 percent of your revenue, they’re basically telling you what to price it at,” said a portfolio manager who had sold 50,000 of her 300,000 Audiovox shares. Sure enough, this portfolio manager’s predictions proved true. In February 2004, Audiovox sold off its cell phone division to Curitel, a Korean manufacturer. Was Verizon’s advantage here one of the motivating factors that caused Audiovox to sell? It’s worth noting that Toshiba had a 25% ownership of Toshiba. One clue into the internecine struggle might be divined by this press release. David Kerr, Vice President of the Strategy Analytics Global Wireless practice, was quoted as follows:

There was some concern over the relationship between third-party vendors offering products to Verizon and Verizon’s dominance in the telecom industry. In July 2000, the New York Times reported that Audiovox, a mobile handset provider, was selling 80% of its handsets to Verizon. “When you have one customer that controls 80 percent of your revenue, they’re basically telling you what to price it at,” said a portfolio manager who had sold 50,000 of her 300,000 Audiovox shares. Sure enough, this portfolio manager’s predictions proved true. In February 2004, Audiovox sold off its cell phone division to Curitel, a Korean manufacturer. Was Verizon’s advantage here one of the motivating factors that caused Audiovox to sell? It’s worth noting that Toshiba had a 25% ownership of Toshiba. One clue into the internecine struggle might be divined by this press release. David Kerr, Vice President of the Strategy Analytics Global Wireless practice, was quoted as follows:

Toshiba wished to be free to exploit its own strong brand with flow-through impacts from its high performance notebooks and other electronics product portfolio. Now, Toshiba is faced with bowing to the wishes of a threatening competitor targeting the same segment Toshiba has traditionally targeted. Toshiba, a minority interest holder at Audiovox, is likely to lose its opportunity for garnering a meaningful share of the 19 million units flowing through to end users at Verizon Wireless.

While Verizon expanded and earned more profits, its workforce was becoming increasingly unhappy. On July 28, 2000, the Communications Workers of America authorized its leaders to call a strike at 12:01 AM on August 6, if Verizon would not meet its demands.

With both Verizon and the unions unable to settle upon a new contract, telephone operators and line technicians walked off the job. Two unions — the CWA and the International Brotherhood of America — represented 33% of Verizon’s workforce. (The CWA represented 72,500 Verizon workers.) One of the major stumbling blocks for this strike involved the employees at Verizon Wireless, the majority of whom did not have union representation. The CWA’s Jeff Miller pointed out at the time that there was a staggering pay difference between a union-covered customer service representative (topping out at a $44,000 annual salary) and a non-union CSR ($33,000). There were also concerns by the unions about undue stress placed upon CSRs. The workers weren’t getting adequate breaks and were often working forced overtime. And the nonunion workers were paying out of pocket for their health plans. In the days before the strike, Verizon took steps to prevent pro-union literature from being distributed at call centers and further asked which of its workers supported the unions. Like the treatment that Verizon would extend to its customers, Verizon was insisting on a five-year contract instead of a short-term contract accounting for the rapid changes in the telecom industry.

Of course, just as it had eluded the FCC, Verizon also had a plan in place to deal with its workers that would eventually involve outsourcing its labor to India. And the exact way in which Verizon overhauled its workforce will be taken up in future installments of this series.

I don’t think the lackluster business had much to do with Michael Cera. But it’s worth observing that Cera has yet to prop up a phenomenally successful Hollywood movie on his presence alone. He’s found commercial success as a supporting character, although Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist, a $10 million movie that grossed $33.5 million, might qualify as a modest success. But when one considers that Scott Pilgrim‘s budget was closer to $100 million, the decision to use Superbad/Juno momentum as a selling point wasn’t terribly wise. Cera, assuming audiences haven’t tired of him by now, will probably be just fine if he can figure out a way to reinvent his one-note Williamsburg hipster schtick and keep his acting roles confined to second bananas. The man lacks leading man gravitas, and now has the commercial track record to prove it.

I don’t think the lackluster business had much to do with Michael Cera. But it’s worth observing that Cera has yet to prop up a phenomenally successful Hollywood movie on his presence alone. He’s found commercial success as a supporting character, although Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist, a $10 million movie that grossed $33.5 million, might qualify as a modest success. But when one considers that Scott Pilgrim‘s budget was closer to $100 million, the decision to use Superbad/Juno momentum as a selling point wasn’t terribly wise. Cera, assuming audiences haven’t tired of him by now, will probably be just fine if he can figure out a way to reinvent his one-note Williamsburg hipster schtick and keep his acting roles confined to second bananas. The man lacks leading man gravitas, and now has the commercial track record to prove it.

In April 2000, Bell Atlantic was working out the details of a merger with GTE it had initiated the previous year. The deal was nearly done, awaiting FCC approval. But Bell Atlantic’s wireless communication unit needed a new name. Bell Atlantic’s wireless unit was in the process of merging with the wireless division of Vodafone AirTouch.

In April 2000, Bell Atlantic was working out the details of a merger with GTE it had initiated the previous year. The deal was nearly done, awaiting FCC approval. But Bell Atlantic’s wireless communication unit needed a new name. Bell Atlantic’s wireless unit was in the process of merging with the wireless division of Vodafone AirTouch.  Bell Atlantic

Bell Atlantic  Whatever Kennard’s current feelings are for Verizon, one thing is beyond dispute.

Whatever Kennard’s current feelings are for Verizon, one thing is beyond dispute.  There was some concern over the relationship between third-party vendors offering products to Verizon and Verizon’s dominance in the telecom industry. In July 2000,

There was some concern over the relationship between third-party vendors offering products to Verizon and Verizon’s dominance in the telecom industry. In July 2000,