Ross McElwee is most recently the director of Photographic Memory.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Stepping away from the memories.

Guest: Ross McElwee

Subjects Discussed: Walker Percy’s “certification,” Heidegger’s Alltäglichkeit, whether social media and YouTube can capture the essential quality of “everydayness,” patterns and layers of meaning discovered through the act of filming one’s life for decades, whether or not people have the patience to sit through a two and a half hour movie these days, how McElwee’s cinematic voice has altered with Photographic Memory, the use of Ken Burns-like music for a photographic montage, why McElwee decided to look backwards instead of tackling the present, problems in passing on the McElwee legacy, Adrian McElweee plugged into technology at the expense of conversation, patriarchal dissing, the imprecision of father-son parallels, the godfathers of the cinéma vérité movement, recreating the moon shot from Sherman’s March, the pernicious influence of the YouTube confessional, Time Indefinite as the obverse of Photographic Memory, filming a tumor for 72 seconds, why Marilyn Levine was not included in Photographic Memory, whether removing a family member from a film offers the truth about a dynamic, divorce, preserving privacy while remaining transparent, meeting Josh Kornbluth in Six O’Clock News, McElwee making “fiction films,” the middle ground between fiction and truth, Tolstoy’s maxim about novels not revealing everything, Andy Warhol’s Empire, why Charleen Swansea hasn’t appeared in McElwee’s recent films, a rare McElwee complaint about irrelevance, compartmentalizing the home environment and France, an adamant yet insignificant moment about a dish which caused Our Correspondent to question its significance, the future of documentary filmmaking and reality TV, Catfish, whether the marvel of the everyday will be informed by seducing the audience over questions of truth, the hidden rat at the motel in Bright Leaves, marveling over quotidian details, Steve Im in Six O’Clock News, conversation vs. dramatic evening news elements, when it’s easier to have conversations with strangers, the virtues of sitting still in one place, apocalyptic elements in McElwee’s films, being informed by lingering anxieties about the end, the harmful effects of smoking, confronting your own mortality, how Adrian’s presentation has transformed in McElwee’s films, fishing, the world divide between those who have kids and those who don’t, periods in life when kids are delightful, whether most people remember the last names of all their lovers and roommates, McElwee’s early attempts to write fiction, being inspired by limitations, how libertine digital shooting has impacted documentaries, and the dangers of not being selective enough when making am ovie.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I’m sorry I didn’t wear my Opus shirt. I couldn’t find one. I don’t think they even make them anymore. I was expecting you to come in and film me or something.

McElwee: Well, that can be arranged. I’ve got a little camera right here. (picking up iPhone)

Correspondent: Oh, I see. Well, I’ve got mine right here. (picking up Galaxy) So I know you wrote an essay on Walker Percy’s The Last Gentleman, which is very interesting. Because I’ve seen your films and they really make me think of what Percy said about “certification” in The Moviegoer, which of course is taken from Martin Heidegger’s notion of Alltäglichkeit, “everydayness” in Being and Time. This idea where we go about our lives, we’re always sort of reflecting on what the meaning of this is. And he said that it was essential. So I’m wondering. How can the video medium, which you have actually gravitated to for the first time with this film, and social media in our present landscape take into account this notion of everydayness? I mean, this film almost seems to be an argument for and against it. So what of this?

McElwee: That’s a question? That’s an essay! (laughs)

Correspondent: Well, we do essay questions and answers here. It’s sort of similar to your films, I think. (laughs)

McElwee: It is. It actually perfectly complements my whole way of making films. Because it’s a very complex thing that you’re asking of me. And to me, filming the everyday, filming little moments from everyday life, is totally essential to understanding what life as a whole is about. I think it’s somehow not recording of any specific moment of life that leads to a richer understanding or a deeper presentation of the meaning of that particular life. But it’s the accretion of all of these things and the overlapping, the patterns, the resonances of daily moments filmed that resonate with things you’ve already seen before. And I find as I get older, as I film my friends and my family, that I see patterns and layers of meaning that would not have been there if I had just filmed them one time. So I think it’s partially that curiosity about the moment of being in the present. And that’s very, very important to my filmmaking. And yet now there’s also a kind of layering that seems to be happening de facto, which is because I’ve been filming for a long time. I’m led to putting together combinations of shots and scenes and moments that span decades. And I have the luxury of doing that now. Because I’m getting older. One of the few benefits of getting older.

Correspondent: The films have gotten shorter, however. Interestingly.

McElwee: Yeah, that’s partially because people don’t have the patience to sit through two and a half hour films anymore.

Correspondent: I do.

McElwee: Well, you’re not the typical viewer.

Correspondent: Well, the interesting thing, aside from the fact that this is shot on video, is that there are a number of surprises about this film, aesthetically speaking, where it just does not seem like a Ross McElwee film. We have, of course, the photos with the music. And I was like, “Am I watching a Ken Burns movie or am I watching a McElwee movie?”

McElwee: Right.

Correspondent: Or even the fact that you gravitate more towards the past instead of the present.

McElwee: Yes.

Correspondent: You know, if you are altering your voice to fit the needs of what is required today, is it truly a genuine McElwee movie?

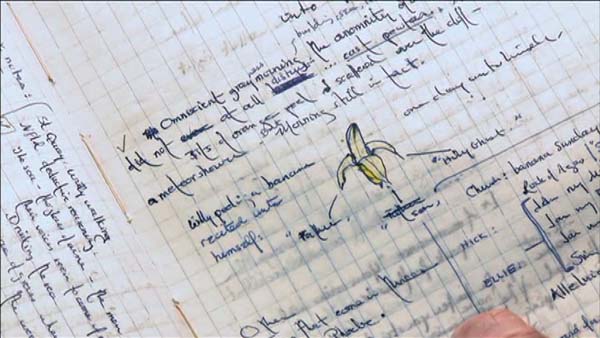

McElwee: No. Well, I’m not altering the voice because of marketing. There’s no way that I’m doing that. But I think it really is a matter of becoming older. I know, for me, for having kids or at least a son who’s a different generation, I’m starting to wonder, “What is this tension that I feel with my son? And why does this seem so extreme?” And that led me to go back to my own past. And I think in doing so, I did fine. I wasn’t shooting film back then and I don’t have images, moving images, to call upon, to represent what was happening at that point in my life. But I do have still photographs. And so, yes, there’s still photographs in my film and it is the first time I’ve used them this extensively. You’re absolutely right about that. And it’s the first time I’ve used stretches of music the way that I have in this film. Music has been in all my films. It’s diegetic. It comes out of the filming itself and the filming environment.

Correspondent: But the music comes before the voice. Whereas in previous films, the voice has ushered in the music.

McElwee: Yes, that’s true. Although I do….yes, you’re right. You’re right. That’s a different way of using music. But I think I felt that these were raw materials that I had available, which represented what my life was like at that time. Therefore, I had to draw on them. And it did make a different kind of film. Of course, the other large difference was that I’m much older now. And so there’s much more to look back on. So that way does become more “historical.”

Correspondent: Much more to look back on? What about looking forward? I mean, literally. I was shocked watching this movie. Because I was expecting the cross-country quest of some kind. But, no, it really is going backwards towards events that are half a lifetime ago. I mean, why should they define who you are in the present? They certainly haven’t in other films that you’ve made.

McElwee: No. And I think it may be a one time departure. But I feel that I have now earned the right to make whatever film I wanted to make and that was the film I wanted to make. And I think it’s mainly because of what I say in the beginning of the film. It’s that I’m a little stymied by my relationship to my son. And I’m confused by the directions he’s going in. And those directions are somewhat representative of his entire generation. But I’m also smart enough to realize that my father had the same questions about me. I didn’t go to medical school. That’s so puzzling. “Why would you not want to do something that would guarantee you a comfortable and fulfilling life?” No, I wanted to become a filmmaker. What is that all about? He must have really wondered about those things.

Correspondent: But the difference between you and your father, and Adrian and you, is that we have this image you have throughout your films of your father showing how to suture up something and your brother going ahead and participating. You’ve used that repeatedly.

McElwee: Yes.

Correspondent: In this, it’s almost like you’re the hired cameraman for Adrian’s movies.

McElwee: Yes.

Correspondent: It’s not necessarily like the passing of a legacy that Adrian rejects, although Adrian also adopts the filmmaking guise. So is there really a parallel here?

McElwee: Not a precise parallel. But there’s some irony too in there. I become Adrian’s camerman at the end of the film and I think that’s meant to be somewhat humorous. People understand that. I’m doing documentaries and determined to do fiction. Not only that, but I become his cinematographer. So, yeah, it’s clearly a departure for me to go in some of the directions I’ve gone in too. But I think it’s very healthy. Why not try something you haven’t tried before? And I’ve done it. Whether I’ll do something similar again remains to be seen.

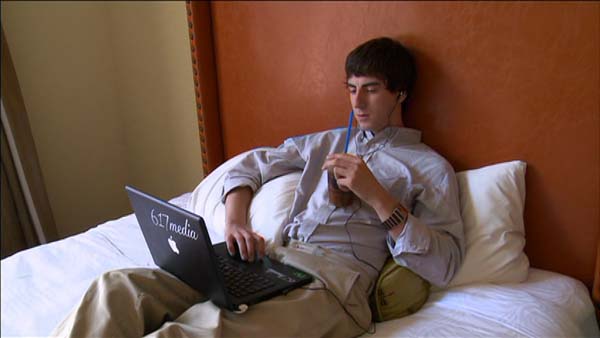

Correspondent: Going back to adjusting to recent developments of the last five or six years — smartphones, social media, and so forth — one of our first images of Adrian. He is plugged into his laptop, quite literally. He has the laptop in front of him. He has the headphones. He has this massive cafe drink with a bright blue straw. And you’re trying to say, “I need your full attention.” And he refuses this. And this to my mind — because I saw your film twice. The first time, I was horrified by this. The second time, I actually came to sympathize with Adrian a little bit more.

McElwee: Right.

Correspondent: But I initially thought, “My God, he’s a spoiled brat. Here he is. The great Ross McElwee is being dissed by his own son!”

McElwee: But that’s his job as a son. Is to diss his dad.

Correspondent: Yeah, but diss in that sort of way? I mean, not have a meaningful conversation with you? Because it seems that you clearly establish, especially when you drag out all of your old notebooks and all of your old photos, there’s meticulous ideas that you set down in your youth and he’s frivolously typing away on his computer.

McElwee: Well, see, my father through I was frivolously scribbling away in my notebooks. It’s like so judgmental of fathers to be that way about their sons.

Correspondent: Or viewers to be that way about patriarchal relationships.

McElwee: Exactly. And the other thing that you can say is, “Well, yeah, he’s busy texting and listening to some conversation at the same time. He’s multitasking and he doesn’t even hear me when I ask the question or acknowledge that he’s heard me.” But what am I doing? I’ve got a digital camera on my shoulder. Who am I to criticize him for being wrapped up in his technology when I’m also wrapped up in my technology?

Correspondent: Well, you weren’t in the camera shot. But I’m pretty sure you weren’t holding a beverage. I’m pretty certain.

McElwee: That’s true.

Correspondent: He had more distractions than you going on.

McElwee: Or he’s just more ambidextrous than I am.

Correspondent: (laughs) Ambidextrous. But I mean, you say that it’s pretty much the same thing. But I would argue, given all the additional impediments from Adrian, that it’s not. That your quest into France was a quest for the usual frivolities of falling into weird relationships. I mean, you have the image of your son next to his girlfriend and there are two laptops there. I mean, that’s a fundamental difference that disrupts the parallel. So what of this? Is there? Can you actually adopt a parallel between your own life and Adrian’s?

McElwee: No, of course. It’s never precisely the same from generation to generation. We all know that. And I think the things that you point out visually were stunning to me when I actually saw them through the viewfinder. The two laptops opened at right angles to each other at a cafe table.

Correspondent: You didn’t notice when you were filming? It’s sort of like the rat in the motel [from Bright Leaves].

McElwee: Well, I did notice when I was filming. Because I thought, “Ah! This is the image I’m looking for.” I didn’t tell them to do that. But from the minute I saw this, I said, “I’m going to film this. Because it just seems so appropriate.” But I think it’s unfair to be too critical of Adrian and his generation for being so wrapped up in this technology. Because it’s available. And I was shooting 16mm film because it was suddenly available in a portable sense. You could put these cameras on your shoulder and go into the world for the first time. That was the whole cinéma vérité revolution. You know, my dad didn’t understand any of that. He thought it was crazy. In fact, at the very beginning, so did most funding agencies. Public television. Arts agencies. Nobody got it. That this was going to be something significant. That you could take technology into the world and interact with it on its own terms. As opposed to bringing people into the studio and interviewing them. Or recreating things the way Flaherty did. Directing it as if it were a fiction film. Using people from real life. And, in fact, it took a while for people to understand the possibilities of cinéma vérité. This was before I began making films. Those guys. [Richard] Lecock and [Albert and David] Maysles and [D.A.] Penebaker. They had to fight to get their kinds of filmmaking seen and shown and produced. So there’s always a learning curve for the rest of them.

Correspondent: And I dig all those guys. But the one commonality throughout all that early cinéma vérité is that there is a concern for capturing the human as opposed to cutting reality up into a stylistic mélange that gets in the way of really grasping with life. I mean, you try to recreate that famous moon shot from Sherman’s March in this film, but we see that we have all these buildings and your monologue is there. But the moon is more insignificant on video and it’s populated by all these buildings and so forth.

McElwee: Right.

Correspondent: Clearly you’re aware that this is either fading or this is in competition with the YouTube confessional/YouTube star movement. And so forth. I mean, where do you fit in? Is there a place for you, do you think?

McElwee: In this? Yeah, that’s a good question. I’m not really trying to tailor my films for any particular generation or any particular venue. I didn’t know where this film was going to end up. It was commissioned by French television. But aside from that, I had no idea where it would end up. And even that was an obscure presentation and platform. It was a late night experimental television series. And I was very happy to accept their commission and make this film. But I didn’t know what kind of film it would be. And I didn’t feel like I could tailor it to suit any particular category or any particular audience. And so there’s a way in which perhaps I’m shooting myself in the foot by not really thinking more about where these films are destined and is there a way I can make them more accessible to the younger generation who will then download it from their computers. I just…I can’t think like that. For whatever reason, I’m just driven to make a film because I want to make it on my own terms.

The Bat Segundo Show #491: Ross McElwee (Download MP3)

The most truthful moment contained within Roberta Grossman’s documentary,

The most truthful moment contained within Roberta Grossman’s documentary,