(This is the first of a five-part roundtable discussion of Ellen Ruppel Shell’s Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture. Other installments: Part Two, Part Three, Part Four, and Part Five.)

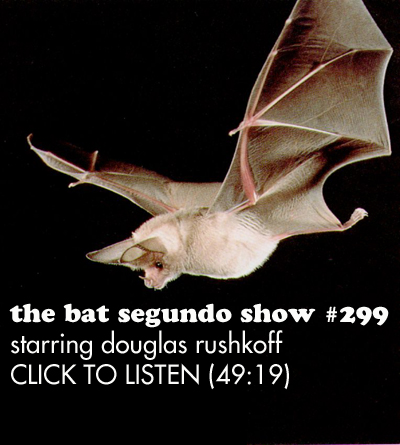

Since present economic developments have caused nearly all of us to reconsider just how we spend our money, I selected Ellen Ruppel Shell’s Cheap for our latest roundtable discussion. For those readers who aren’t familiar with the roundtable discussions, this website will be devoting the entire week to discussing Ruppel Shell’s book, and we’ll be serializing the conversation in five chunky installments from Monday through Friday. The discussion, as you’ll soon see, got quite spirited at times. But the hidden costs of “cheap,” as it turned out, proved to be quite complicated. Be on the lookout for cameo appearances, some unexpected revelations, and a lengthy podcast interview with the author. And feel free to leave any additional thoughts or personal experiences in the comments. Your communications will help many of us to understand and rethink a very important topic.

Edward Champion writes:

“Remember, time is money. He that can earn ten shillings a day by his labor, and goes abroad or sits idle one half of that day, though he spends but six pence during his diversion or idleness, ought not to reckon that the only expense; he has really spent, or rather thrown away, five shillings besides.” — Benjamin Franklin

There’s a bodega that opened up in my neighborhood with a bright and muti-hued awning reading GOURMET DELI. But I’ve examined the goods. The owners are using the same Boar’s Head meat found at nearly every place packing hero sandwiches in the five boroughs. But what this deli has done is undercut the competition. Another deli, situated just one block south, sells a turkey hero for $4.50. About three months ago, this deli had raised its price by a quarter. The regulars still grumble. After all, everything’s going up. Metrocards, milk, beer. But they slide over their four paper George Washingtons and their two copper-nickel George Washingtons. The hero remains a “good deal.”

There’s a bodega that opened up in my neighborhood with a bright and muti-hued awning reading GOURMET DELI. But I’ve examined the goods. The owners are using the same Boar’s Head meat found at nearly every place packing hero sandwiches in the five boroughs. But what this deli has done is undercut the competition. Another deli, situated just one block south, sells a turkey hero for $4.50. About three months ago, this deli had raised its price by a quarter. The regulars still grumble. After all, everything’s going up. Metrocards, milk, beer. But they slide over their four paper George Washingtons and their two copper-nickel George Washingtons. The hero remains a “good deal.”

But the new “gourmet deli” now offers the same sandwich for $4.25. The old price. The cheaper price.

And after reading Ellen Ruppel Shell’s fascinating book, I now find myself acutely curious about whether this “gourmet deli” is making the proprietors any money. I find myself morally compromised when purchasing a hero sandwich. And I’m wondering how many of you have experienced similar feelings. I want to know if every ingredient has been obtained through equitable labor. But unless I spend a good deal of my time asking about wholesalers and suppliers in the neighborhood, I’m probably not going to get even half of the answer.

The great irony with the Ben Franklin quote (which is dredged up in the book when Ruppel Shell mentions Ben & Jerry’s Free Ice Cream Day, which I’ll get to in a minute) is that we’ve become so dependent upon getting the best bang for our buck that all other time-based considerations fall by the wayside. Ruppel Shell brings up the telltale consumer who is willing to drive 75 miles out of their way to an outlet store to buy inferior goods for a cheaper price. She even describes a personal example: a man who drove up 75 miles to check out her car (on sale), noticed a few scratches, and then drove right back home. This is a curious trade-off, running contrary to Franklin’s wisdom. (Then again, we also live in a nation in which our thrifty founding father appears on one of our most expensive dollar bills.)

The great irony with the Ben Franklin quote (which is dredged up in the book when Ruppel Shell mentions Ben & Jerry’s Free Ice Cream Day, which I’ll get to in a minute) is that we’ve become so dependent upon getting the best bang for our buck that all other time-based considerations fall by the wayside. Ruppel Shell brings up the telltale consumer who is willing to drive 75 miles out of their way to an outlet store to buy inferior goods for a cheaper price. She even describes a personal example: a man who drove up 75 miles to check out her car (on sale), noticed a few scratches, and then drove right back home. This is a curious trade-off, running contrary to Franklin’s wisdom. (Then again, we also live in a nation in which our thrifty founding father appears on one of our most expensive dollar bills.)

While Ruppel Shell presents a number of convincing developments that partially explicate this mentality (to name just three, the fixed price introduced with John Wanamaker’s price tags, Victor Gruen’s use of social space to develop the “shopping towns” that are now ubiquitous and that keep shoppers hanging around, and the “affordable luxury” seen with Coach discount leather), I’m wondering if you folks feel that Ruppell Shell is being too hard on the consumer. I mean, we can’t all be mindless sheep, can we? Is it not possible that our trips to outlet malls or our determination to spend endless amounts of time searching for the best deal may not be entirely tied into discount culture? There is such a thing as window shopping. And maybe we want to waste our time finding odd or unusual things. (I will confess that one reason I like to check out some of these dollar stores is to marvel at the shoddy merchandise. I mean, how often do you see bubble gum from 1972 that’s still on the market? Very rarely do I buy anything.)

Before we plunge into Ruppel Shell’s IKEA Billy Bookcase example, which to my mind (and sadly my personal experience), truly reflects a pernicious reliance upon discount culture over quality, I want to first establish whether Ruppel Shell may be inadvertently suggesting that “bargain hunting” might be the new way of wasting time. Does discount culture and consumerism maintain such a hold on American culture that this is now how we spend most of our leisure hours? Should we pin the blame on corporations such as Wal-Mart for injecting capital into small towns and suburbs and establishing a town center? Preexisting local economies may not have been able to do this. Then again, how much of this is illusory? (Ruppel Shell cites a fascinating study from Emek Basker. Basker investigates the so-called “Wal-Mart effect” of prices lowering throughout community stores whenever a Wal-Mart moves into a community. His findings suggest that not all prices fall. Are there other “effects” beyond pricing that create such conditions? And should we blame Wal-Mart or the people who want a Wal-Mart?)

Before we plunge into Ruppel Shell’s IKEA Billy Bookcase example, which to my mind (and sadly my personal experience), truly reflects a pernicious reliance upon discount culture over quality, I want to first establish whether Ruppel Shell may be inadvertently suggesting that “bargain hunting” might be the new way of wasting time. Does discount culture and consumerism maintain such a hold on American culture that this is now how we spend most of our leisure hours? Should we pin the blame on corporations such as Wal-Mart for injecting capital into small towns and suburbs and establishing a town center? Preexisting local economies may not have been able to do this. Then again, how much of this is illusory? (Ruppel Shell cites a fascinating study from Emek Basker. Basker investigates the so-called “Wal-Mart effect” of prices lowering throughout community stores whenever a Wal-Mart moves into a community. His findings suggest that not all prices fall. Are there other “effects” beyond pricing that create such conditions? And should we blame Wal-Mart or the people who want a Wal-Mart?)

Citing Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage is always a good idea to explore in a book of this type – seeing as how free market advocates often dust off this 200-year-old idea and cling to its possibilities like an AIG executive braying for another government bailout. But I’m wondering if comparative advantage is a viable application when we’re talking about consumers who want more than what a local economy might be able to give to them.

I’m also wondering if it’s fair to chide customers for standing in line for Ben & Jerry’s Free Ice Cream Day. Sure, the flavor options are limited. But it’s not as if you’re lining up for melted vanilla ice milk. And, yes, you can always go to another Ben & Jerry’s, slap down three bucks, and get an ice cream immediately. But are people lining up because bargain hunting and consumerism have replaced less conspicuous ways of frittering away our time? Is it the consumer or the corporation who is guilty of letting discount culture and bargain hunting dominate our culture like this? Have we lost the ability to let time simply be time? Why most every action have a monetary value? (That last question may involve bringing up Chris Anderson’s book, which I’ll let the others bring up, for obvious reasons.)

That may be a lot to throw into the fray, but I think I’ll close this opening sally by returning back to my neighborhood. In the past nine months, my neighborhood has seen numerous mom-and-pop stores close their doors due to the economic downturn and the unsustainable rents. In fact, last summer, a bodega was forced to close its doors. It seemed highly successful. It was the place where everybody went, largely because it had more space than the other bodegas and the prices were cheaper. But as it turned out, the owner couldn’t pay the rent on the place for three months and was forcibly evicted. What does it say about our reliance on discount culture when a man will enter into default because the customer is always right, even when he insists on an unsustainable price in an unsustainable economy?

Robert Birnbaum writes:

The recent spate of social science books doting on and then purporting to explain our irrationality in all manner of behaviors (especially consuming) is somewhat interesting and amusing (Gladwell excepted). The examples and case studies range from compelling anecdotes to something less. But if the intention was to blind us with science — well, no dice.

This will no doubt be viewed as simplistic. But given the preexisting gap between various regions of our cognitive faculties, the incessant message droning in the back and foregrounds of our lives to consume, to acquire, to converse about our acquisitions, write about them, devote publications and books to them and, to top it off, to be told in the midst of a national crisis that it was patriotic to shop, this very much guarantees senseless consumption behavior.

As far as I have read, I suppose the history of retailing does provides revelations but the conclusion I am heading toward is that, when retailing moved to large and then gigantic organizations, shopping became an adversarial contest in which consumers were bound to lose.

More TK

Peggy Nelson writes:

Some initial thoughts, building on what Ed and Robert have begun.

I think Ruppel Shell is trying to get at more than wasting time. I think she’s posing the stronger argument that bargain hunting blinds us to the hidden costs of bargains because of the psychological thrill (at the individual level) of getting more than what you paid for — in some sense. She’s making a two-pronged attack on the structure of discount economy and culture — that the consumers have their part of the bargain to uphold (or dismantle) as much as the corporations and the government have their part to be forced into acknowledging and changing — at the behest of the consumers, qua citizens.

I just finished Douglas Rushkoff’s Life Inc., which speaks to many of these points as well. “Big” has a market advantage in our economy; it’s not a level playing field. Big corporations have easier access to money. The corporations can get bigger loans, at lower rates, than the little guys. They can also afford big-time lobbyists, and there are any number of instances where lobbyists go back and forth between their lobbying jobs and the industries they were lobbying for. Government is, in many crucial ways, out of our hands at this point. But what remains very much in our hands is our own buying habits.

I just finished Douglas Rushkoff’s Life Inc., which speaks to many of these points as well. “Big” has a market advantage in our economy; it’s not a level playing field. Big corporations have easier access to money. The corporations can get bigger loans, at lower rates, than the little guys. They can also afford big-time lobbyists, and there are any number of instances where lobbyists go back and forth between their lobbying jobs and the industries they were lobbying for. Government is, in many crucial ways, out of our hands at this point. But what remains very much in our hands is our own buying habits.

I am normally not a fan of the “pick up your own litter” school of thought. It’s not that I think that picking up your own litter is bad. I think it deflects attention and analysis from the larger and more systemic causes of trash. But in this case, I think Ruppel Shell does a good job tallying the problems on both sides of this tricky equation. There is something that the individual needs to do here.

I know that, if you make very little money as a cashier at Wal-Mart, you’re not going to be able to shop at Whole Foods. But that’s exactly part of the problem too and part of the hidden costs Ruppel Shell brings to light: discount pay scales, on both the supplier and the retail ends, are a huge cost that is not reflected in the item’s price. It’s all connected. Decent-paying, somewhat-meaningful labor, with local, community-based commerce, is more affordable than the behemoth we have now.

I think Ruppel Shell’s a little weak on this final point. She does mention it, but I think it needed a little more ink. My main qualm with this book was its overreliance on very similar studies by all these B school profs. They are not the B-all and end-all! Had she not felt the need to underline every claim with a study as a sort of preemptive strike, Ruppel Shell would have had more pages to draw out the final links in the chain a little more strongly.

Also, Ed, I think you’re making a really important point about time, and how it need not/should not always be reduced to money. There is a tendency to focus on homo economics when talking about the economy, that comes from both the right and left, that we need to guard against. You’re right to point out that we’re more than just consumers, that our habits, even in the marketplace, are about more than the bottom line. We’re more than the money!

Colleen Mondor writes:

The one thing I thought Ruppel Shell conveyed quite effectively is that “bargain” no longer equates to quality in our culture. She used the IKEA example well here when she noted that we buy the cheap shelves, knowing that these shelves won’t last more than a few years. But because these shelves are cheap, we think that’s fine. So it’s as if we’ve forgotten (in a cultural sense) what the word “bargain” truly means. It’s not just about the price; it’s about getting a good deal, if you spend money on something that won’t do the job for long. But are you really getting a good deal?

Personally, I grew up on cheap culture out of necessity. My parents just didn’t have much money and we lived paycheck to paycheck. We couldn’t see the big picture because we couldn’t afford it. Period. But what’s interesting is that, as my parents grew older and could afford to invest in things that would last, neither was able to change their thinking. My mother still struggles to spend more than $15 on a shirt even when she knows that it will likely stretch, fade, etc. She just has certain price points in her head and she just can’t let them go.

Personally, I grew up on cheap culture out of necessity. My parents just didn’t have much money and we lived paycheck to paycheck. We couldn’t see the big picture because we couldn’t afford it. Period. But what’s interesting is that, as my parents grew older and could afford to invest in things that would last, neither was able to change their thinking. My mother still struggles to spend more than $15 on a shirt even when she knows that it will likely stretch, fade, etc. She just has certain price points in her head and she just can’t let them go.

Overall, I thought Cheap was fascinating. The book provides readers with much food for thought.

Miracle Jones writes:

Here are some preliminary preoccupations I had while reading this book:

1. The startling and unironic revelation that Ruppel Shell would rather eat horses than go without meat (taken from the “Note to Readers”). I admire her honesty, and it’s a brave assertion to make, considering the potential market for this book.

2. The startling free pass that Amazon receives from Ruppel Shell, despite Amazon being a corporation currently profiting from the economic collapse like no other and raking in ludicrous profits that look a good deal like blood to me. She mentions Amazon once when she talks about unfair pricing models, and, once again later, when she refers back to that passage. Evidently, Amazon got caught charging the old customers more than the new ones. Jjust like a drug dealer. Why wasn’t there any further analysis of this pricing impact? Ruppel Shell knows for a fact that her audience consumes the commodity of books. Doesn’t Penguin have some “most favored nation” status with Amazon? Questions abound.

3. “A similar scenario is played out by urban street vendors today who claim that the Rolex and Cartier watches lining their jackets are not counterfeits but somehow ‘fell off a truck’ on their way to Neiman Marcus.” I have not seen this “scenario” since cartoons from the 1950s. Lining their jackets? Are they also wearing Hamburglar masks?

4. I wanted to read an entire chapter about what Daniel Ariely discovered when he had male college kids masturbate and then asked them sexually charged questions to determine the exact point when their “reason” disappeared and they could no longer be convinced to wear a condom. What questions did he ask? Were the college students paid after they came? Can I do this experiment? Or do I need a degree?

5. “A psychological state known as the ‘Gruen transfer’ has come to signify when a ‘destination buyer’ shopping for a specific purchase loses focus and starts wandering in a sort of daze, aimless and vulnerable to the siren call of come-ons of every sort.” I suspect that most of America lives in a perpetual “Gruen transfer.”

6. “Two feedlots outside Greeley, Colorado, together produce more excrement than the cities of Atlanta, Boston, Denver, and St. Louis combined. Trucking the stuff off is impractical. One alternative popular among big companies is to spray liquefied manure into the air and let it fall where it may, coating trees and anything else that happens to be in its path.” What?!?

Erin O’Brien writes:

I agree with much of what Miracle said. There are no less than 21 pages in my copy of Cheap that I’ve flagged.

If anything, I thought Ruppel Shell was too soft on the consumer. The book is a dense brew of numbers and statistics, but it mostly served to prove what I already knew: that the American dream has rotted to its core. I suppose this could be globally extrapolated, but I’ll keep my comments in my own backyard.

The idea that parents worked hard because they wanted better for their children maxed out years ago, perhaps in the ’70s. Somewhere along the way, the definition of high quality life became “More More More.” We have so much stuff that our stuff has stuff. We can’t get to the stuff we need because the stuff we don’t need is in the way. We rack our brains trying to think of gifts for our loved ones because they already have everything they want or need.

People who amass the most junk are the ones filling emotional and intellectual voids. That’s always been the case. The happier and more balanced people are, the less likely they are to rely on mountains of things. And if the American Dream is reduced to “More More More” stuff, the less money you have, the harder you’ll try to get as much of the stuff as you can for it (read: The Dollar Store). And as far as the junkiness of the junk is concerned, the cliché “you get what you pay for” got old and tired for a reason.

Sure, everybody wants to do right by their dollars. But how do you really tell if someone’s cheap? Watch how they tip the waiter.

I wanted more on cheap culture’s implications from this book, more on how a two-by-four has shrunken over the years and how drywall has become thinner and thinner. Not surprisingly, the most successful parts of Cheap for me were the ones that detailed the true cost of “cheap,” wherein we visit the shrimp farms and consider the implications of China’s labor practices.

This book represents a stunning amount of work, but I must say that I thought the “slot jockeys in track suits and sneakers” on page 88 was just plain mean. Why does Ruppel Shell include this description? This sort of commentary is particularly off-putting when just a few pages later, Ruppel Shell fawns over Prof. Naylor in her “Diane Van Furstenberg-style wrap dress accented with a stunning Plino Visona handbag.” That was the sort of thing that elicited flags from me. Unfortunately, it also eroded the book’s credibility.

The other day, I saw a woman with four small children foraging through a Goodwill drop box. She was pulling out clothes and putting them on the kids, who soon all had on multiple shirts and sweaters in the summer heat. Welcome to the cheapest shopping spree of them all. But I got the distinct feeling that this woman was no bargain hunter. This was a woman doing what she had to do. Although I understand and appreciate all the studies and arguments in Cheap, I wonder how much that woman would care about any of them. Who would tell her not to shop at The Dollar Store in order to delight those kids with a silly little toy?

There are lots and lots of people on this earth. Whether they’re clothed in “track suits,” Goodwill cast-offs, or they’re toting Plino Visona handbags, they all want food and shelter, which presents us with immense and complex problems. We won’t find the answers within the inviting aisles of a Wegmans.

“She even describes a personal example: a man who drove up 75 miles to check out her car (on sale), noticed a few scratches, and then drove right back home.”

That was from one of Ed’s comments.

I found Ruppel Shell’s anecdotes weak, such as that story about selling her used car. How extensively did she interview this fellow? Is there any guarantee that he didn’t have additional business in that area? A man comes and looks at her used car. Maybe he was lying about why he declined to purchase it. None of it really matters. But when I see a writer putting forth a serious nonfiction effort, and including this type of chatty personal anecdote, it’s dodgy to say the least. At worst, it can make a reader feel manipulated. All that story told us was what one guy had to say about one used Honda. To extrapolate it as commentary on how and why people spend their money is a fool’s game.

Here is another detail I flagged: On page 133, Ruppel Shell describes an IKEA table. “It looked just the right size to host a child’s tea party.” Why didn’t she go online and find the exact dimensions and let me judge the size of the table for myself? I’m a big girl. I can decide if a piece of furniture is appropriately sized or not. I realize this is a tiny quibble, but the text is inundated with these types of brush strokes. Every one risks making me feel manipulated, which in turn dulls the sharper points in the book.

As far as your hero sandwich is concerned, Ed, I did feel morally dirty about the frozen shrimp in my freezer after reading Ruppel Shell’s description of the shrimp farms, which is why I found that section so successful. But even here, Ruppel Shell recalls a time when shrimp was a wild and expensive delicacy. There’ a bit of wistful nostalgia in her description. But as she says herself, the good old days weren’t always so good and now wild fish populations are in grave danger al over the globe. Here’s one story to that end by Johann Hari for the Independent:

As far as your hero sandwich is concerned, Ed, I did feel morally dirty about the frozen shrimp in my freezer after reading Ruppel Shell’s description of the shrimp farms, which is why I found that section so successful. But even here, Ruppel Shell recalls a time when shrimp was a wild and expensive delicacy. There’ a bit of wistful nostalgia in her description. But as she says herself, the good old days weren’t always so good and now wild fish populations are in grave danger al over the globe. Here’s one story to that end by Johann Hari for the Independent:

The harder society cracks down on irresponsible farming, the greater the pressure on wild oceanic populations. Once again, there’s no easy answer.

Throughout all of this, I feel privileged to discuss and read about these issues. People who are cold and hungry couldn’t care less about whether or not a warm plate of food was ethically produced. If all you have is one dollar and a loaf of bread is $1.73 at the discount grocer, it ceases to be cheap. That’s the most mandatory and difficult part of this entire topic, the subjectivity of it.

Sarah Weinman writes:

I have much to say on Cheap and will do so soon. But I wanted to counter Erin’s point about the potential for manipulation when personal anecdotes are included in serious nonfiction. Part of that is publisher-driven; they want the serious medicine washed down with some degree of contextual personalization, if not entertainment. It’s not enough to be treated to the facts, backed up scrupulously (and Ruppel Shell impressed the hell out of me with her endnotes, in large part because this type of research is too often left on the cutting room floor — I’m thinking of the unclear endnotes in David Michaelis’s Schulz and Peanuts, which was a very good biography that could have been stellar with clear and comprehensible references!); the serious nonfiction writer has to have a great voice and answer the pivotal question of “Why should the reader be reading your book?” Too much of the author is a problem, but just a little bit seasons it just right.

Which is to say, I didn’t have a problem with that personal example. It passed my believability test and brought home the point that people will add needless costs in order to find the lowest price, thus negating the price reduction in the first place.

Peggy Nelson writes:

I’d like to look at the book’s great unasked question, which is the reason she was compelled to write it (and to have us read it): What to do about hidden costs? Ruppel Shell spends significant time tracing and exposing the hidden costs of “cheap”: personal, social, environmental, systemic. What if these hidden costs were incorporated into the price? “Cheap” would suddenly become prohibitively expensive.

But then what? Okay, so this plastic toothbrush from China is $47.50. Or maybe even $899.99! Well, I’m not buying it, and neither is my neighbor who doesn’t have the financial luxury of buying a nice local sustainable wooden one at Whole Foods for $26.95. But suppose there are no local small manufacturers around, no weekly farmer’s market that could serve the entire community, and no place that doesn’t depend on the vast oil-based chains of import/export.

How do we get from our current system, in which the hidden costs are catching up and twisting us into a vicious downward spiral in all areas, to a more equitable system, in which price reflects real cost, and local/sustainable is the more economical option? In other words, how do we get to Utopia? What are the practical or general steps? Do we need The Revolution? Because we all know how well that’s worked out each time.

Levi Asher writes:

I find myself less excited by this book than the others so far, and less convinced about its arguments. I do admire Ruppel Shell’s mission. I like the type of psychological investigative journalism this book represents. I have a feeling I’d relate to her first book (about modern eating habits) more than I did to this one.

I can’t relate to Cheap because, while Ruppel Shell writes as if every single modern American is caught up in the Kmart Syndrome, I think I’m immune to it in the first place. I don’t feel any emotional attraction to consumer goods and I wouldn’t cross a street to get a bargain. I do like stores like Kmart and Target for their practical simplicity, and I don’t think I ought to be considered part of a brainwashed bargain-hunting horde because of this.

Ruppel Shell is especially on thin ice with me when it comes to IKEA. I have tended to move every few years in my life, and IKEA furniture is exactly what I need. Long term value? Who cares! I don’t need to carry around a cherished antique. I want to pay $70 for a bunch of pressed wood with screws and pre-drilled holes and a funny Swedish name that I can put up in an hour and throw away when it comes time to move again. Maybe I’m crazy, but I always considered IKEA furniture to be an example of Zen perfection in home furnishing. Ellen Ruppel Shell’s book does not make me want to change my ways.

I’ve written in the past about why I think it’s essential for the publishing industry to give up its sick addiction to expensive hardcover publishing and begin releasing new titles in affordable paperback. Here again, my philosophy seems to head-butt directly against Ruppel Shell’s, though really it’s not the hardcover prices that I despise so much as the size. Even as I read some of Ruppel Shell’s better and more intriguing passages in this book — and there are many of these — I wonder how to reconcile Ruppel Shell’s arguments against “cheap” with my own impassioned past arguments against “expensive.” I’m simply at a loss.

What I like best about this book is its psychological contradictions — the fact that people will spend money to get a bargain and then consider that they “won”, the fact that a homeowner will cherish the memory of a couch bought on a “good deal” decades earlier, as if this really mattered at all. This is pointed stuff and I enjoyed reading it.

But it occurs to me that this kind of bargain-hunting, for those who engage in it, must be simply a sport, a hobby. Would Ruppel Shell deny people a hobby they enjoy? Sure, people can spend a ridiculous amount of time hunting pointlessly for bargains. But they can also spend a ridiculous amount of time collecting stamps, or studying baseball statistics, or posting to blogs. Maybe it’s just fun.

I remember once having an argument with a friend at an outdoor rock concert on a summer day. I was about to pay $8 for a bottle of Poland Spring water from an amateur price-gouger, and my friend said I was crazy and the price-gouger was unethical. I didn’t see the problem or the ethical violation. The price-gouger had done the work to truck a Styrofoam container of ice and water bottles into our stadium, and that effort certainly seemed to me to be worth an $8 reward.

I remember once having an argument with a friend at an outdoor rock concert on a summer day. I was about to pay $8 for a bottle of Poland Spring water from an amateur price-gouger, and my friend said I was crazy and the price-gouger was unethical. I didn’t see the problem or the ethical violation. The price-gouger had done the work to truck a Styrofoam container of ice and water bottles into our stadium, and that effort certainly seemed to me to be worth an $8 reward.

The fact that I didn’t mind paying $8 for this water bottle probably means I’m not the target audience for this book. Or should I say the “Target audience”, if you’ll pardon the pun …

Correspondent: But the writing that you did. The times that you had. Surely now, decades later, you remember those times. They matter more to you than the brand name on that sneaker. And not only that. But it seems to me that you had a situation. I had a similar situation in terms of having hand-me-downs and that kind of thing.

Correspondent: But the writing that you did. The times that you had. Surely now, decades later, you remember those times. They matter more to you than the brand name on that sneaker. And not only that. But it seems to me that you had a situation. I had a similar situation in terms of having hand-me-downs and that kind of thing.

There’s a bodega that opened up in my neighborhood with a bright and muti-hued awning reading GOURMET DELI. But I’ve examined the goods. The owners are using the same Boar’s Head meat found at nearly every place packing hero sandwiches in the five boroughs. But what this deli has done is undercut the competition. Another deli, situated just one block south, sells a turkey hero for $4.50. About three months ago, this deli had raised its price by a quarter. The regulars still grumble. After all, everything’s going up. Metrocards, milk, beer. But they slide over their four paper George Washingtons and their two copper-nickel George Washingtons. The hero remains a “good deal.”

There’s a bodega that opened up in my neighborhood with a bright and muti-hued awning reading GOURMET DELI. But I’ve examined the goods. The owners are using the same Boar’s Head meat found at nearly every place packing hero sandwiches in the five boroughs. But what this deli has done is undercut the competition. Another deli, situated just one block south, sells a turkey hero for $4.50. About three months ago, this deli had raised its price by a quarter. The regulars still grumble. After all, everything’s going up. Metrocards, milk, beer. But they slide over their four paper George Washingtons and their two copper-nickel George Washingtons. The hero remains a “good deal.”  The great irony with the Ben Franklin quote (which is dredged up in the book when Ruppel Shell mentions Ben & Jerry’s Free Ice Cream Day, which I’ll get to in a minute) is that we’ve become so dependent upon getting the best bang for our buck that all other time-based considerations fall by the wayside. Ruppel Shell brings up the telltale consumer who is willing to drive 75 miles out of their way to an outlet store to buy inferior goods for a cheaper price. She even describes a personal example: a man who drove up 75 miles to check out her car (on sale), noticed a few scratches, and then drove right back home. This is a curious trade-off, running contrary to Franklin’s wisdom. (Then again, we also live in a nation in which our thrifty founding father appears on one of our most expensive dollar bills.)

The great irony with the Ben Franklin quote (which is dredged up in the book when Ruppel Shell mentions Ben & Jerry’s Free Ice Cream Day, which I’ll get to in a minute) is that we’ve become so dependent upon getting the best bang for our buck that all other time-based considerations fall by the wayside. Ruppel Shell brings up the telltale consumer who is willing to drive 75 miles out of their way to an outlet store to buy inferior goods for a cheaper price. She even describes a personal example: a man who drove up 75 miles to check out her car (on sale), noticed a few scratches, and then drove right back home. This is a curious trade-off, running contrary to Franklin’s wisdom. (Then again, we also live in a nation in which our thrifty founding father appears on one of our most expensive dollar bills.)  Before we plunge into Ruppel Shell’s IKEA Billy Bookcase example, which to my mind (and sadly my personal experience), truly reflects a pernicious reliance upon discount culture over quality, I want to first establish whether Ruppel Shell may be inadvertently suggesting that “bargain hunting” might be the new way of wasting time. Does discount culture and consumerism maintain such a hold on American culture that this is now how we spend most of our leisure hours? Should we pin the blame on corporations such as Wal-Mart for injecting capital into small towns and suburbs and establishing a town center? Preexisting local economies may not have been able to do this. Then again, how much of this is illusory? (Ruppel Shell cites a fascinating study from

Before we plunge into Ruppel Shell’s IKEA Billy Bookcase example, which to my mind (and sadly my personal experience), truly reflects a pernicious reliance upon discount culture over quality, I want to first establish whether Ruppel Shell may be inadvertently suggesting that “bargain hunting” might be the new way of wasting time. Does discount culture and consumerism maintain such a hold on American culture that this is now how we spend most of our leisure hours? Should we pin the blame on corporations such as Wal-Mart for injecting capital into small towns and suburbs and establishing a town center? Preexisting local economies may not have been able to do this. Then again, how much of this is illusory? (Ruppel Shell cites a fascinating study from  I just finished

I just finished  Personally, I grew up on cheap culture out of necessity. My parents just didn’t have much money and we lived paycheck to paycheck. We couldn’t see the big picture because we couldn’t afford it. Period. But what’s interesting is that, as my parents grew older and could afford to invest in things that would last, neither was able to change their thinking. My mother still struggles to spend more than $15 on a shirt even when she knows that it will likely stretch, fade, etc. She just has certain price points in her head and she just can’t let them go.

Personally, I grew up on cheap culture out of necessity. My parents just didn’t have much money and we lived paycheck to paycheck. We couldn’t see the big picture because we couldn’t afford it. Period. But what’s interesting is that, as my parents grew older and could afford to invest in things that would last, neither was able to change their thinking. My mother still struggles to spend more than $15 on a shirt even when she knows that it will likely stretch, fade, etc. She just has certain price points in her head and she just can’t let them go. As far as your hero sandwich is concerned, Ed, I did feel morally dirty about the frozen shrimp in my freezer after reading Ruppel Shell’s description of the shrimp farms, which is why I found that section so successful. But even here, Ruppel Shell recalls a time when shrimp was a wild and expensive delicacy. There’ a bit of wistful nostalgia in her description. But as she says herself, the good old days weren’t always so good and now wild fish populations are in grave danger al over the globe. Here’s one story to that end

As far as your hero sandwich is concerned, Ed, I did feel morally dirty about the frozen shrimp in my freezer after reading Ruppel Shell’s description of the shrimp farms, which is why I found that section so successful. But even here, Ruppel Shell recalls a time when shrimp was a wild and expensive delicacy. There’ a bit of wistful nostalgia in her description. But as she says herself, the good old days weren’t always so good and now wild fish populations are in grave danger al over the globe. Here’s one story to that end  I remember once having an argument with a friend at an outdoor rock concert on a summer day. I was about to pay $8 for a bottle of Poland Spring water from an amateur price-gouger, and my friend said I was crazy and the price-gouger was unethical. I didn’t see the problem or the ethical violation. The price-gouger had done the work to truck a Styrofoam container of ice and water bottles into our stadium, and that effort certainly seemed to me to be worth an $8 reward.

I remember once having an argument with a friend at an outdoor rock concert on a summer day. I was about to pay $8 for a bottle of Poland Spring water from an amateur price-gouger, and my friend said I was crazy and the price-gouger was unethical. I didn’t see the problem or the ethical violation. The price-gouger had done the work to truck a Styrofoam container of ice and water bottles into our stadium, and that effort certainly seemed to me to be worth an $8 reward.