In 2005, film critic Roger Ebert ruffled a few feathers when he suggested that because video games require player choices, games are therefore an inferior medium:

To my knowledge, no one in or out of the field has ever been able to cite a game worthy of comparison with the great dramatists, poets, filmmakers, novelists and composers. That a game can aspire to artistic importance as a visual experience, I accept. But for most gamers, video games represent a loss of those precious hours we have available to make ourselves more cultured, civilized and empathetic.

I can certainly agree with Ebert that video games are, for the most part, showcases for the latest gaming engines, primarily designed so that the individual will drop hundreds of dollars for a next-generation console system or a needlessly expensive video card that will be outdated in a few years (only to be replaced by yet another). We are now in the nickelodeon days, although, as the Wii demonstrates, the game controllers are getting more interesting. But this multi-billion dollar industry is less concerned with the human experience than it should be. It has come close with the Civilization games and the Sims offerings, and may come even closer with Will Wright’s much delayed Spore, an ambitious god game that permits the player to develop a cell and then control the natural development of this cell into a species, and then further manage the species as it plunges into space exploration. I’ve lost many hours feeling an ignoble cathartic thrill when fragging a junior-high schooler who, like me, should probably be reading a book. But I can justify my shameful vicarious pleasure by knowing that this is a medium that has yet to produce a Battleship Potemkin or a Birth of a Nation.

I can certainly agree with Ebert that video games are, for the most part, showcases for the latest gaming engines, primarily designed so that the individual will drop hundreds of dollars for a next-generation console system or a needlessly expensive video card that will be outdated in a few years (only to be replaced by yet another). We are now in the nickelodeon days, although, as the Wii demonstrates, the game controllers are getting more interesting. But this multi-billion dollar industry is less concerned with the human experience than it should be. It has come close with the Civilization games and the Sims offerings, and may come even closer with Will Wright’s much delayed Spore, an ambitious god game that permits the player to develop a cell and then control the natural development of this cell into a species, and then further manage the species as it plunges into space exploration. I’ve lost many hours feeling an ignoble cathartic thrill when fragging a junior-high schooler who, like me, should probably be reading a book. But I can justify my shameful vicarious pleasure by knowing that this is a medium that has yet to produce a Battleship Potemkin or a Birth of a Nation.

To suggest, however, that the video game will never find the same gravitas as cinema is to fall prey to same prejudicial thinking with which intellectuals once castigated cinema in the early 20th century. Let’s not forget that it took the motion picture around thirty years of technological developments before it was considered more than a gaudy amusement. And we have only just passed the 30th anniversary of the Atari 2600.

This New York Times article from September 7, 1913 suggests that the then primitive motion picture was, like the contemporary video game, very much about delivering spectacle to a mass audience. George Kleine, one of the key people who established the film industry in the United states and who had just made a cinematic adaptation of Quo Vadis? with a cast of 3,000 people (then an unprecedented number), is quoted in an eerily comparable manner about the future of the medium”

“I have plans for the future which make everything I have done so far seem to be mere child’s play. The educational end has not begun. Motion pictures will not supplant books in the public schools, according to my opinion, but they will revolutionize our educational system. Instead of being bored, the child will enjoy learning by object lessons conveyed by the use of moving pictures.”

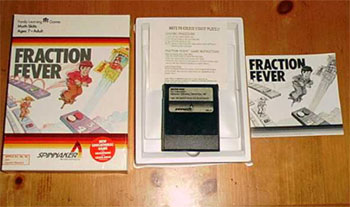

Replace “motion pictures” with “video games” and you essentially have what’s reflected in this 2002 BBC News article, in which a study reveals that games are not a substitute for books, but a way to help children learn. And if, like me, you grew up playing Fraction Fever (the ROM is here, if you’re an emulator geek) or any of the other Spinnaker titles, perhaps there is some credence to these theories.

Replace “motion pictures” with “video games” and you essentially have what’s reflected in this 2002 BBC News article, in which a study reveals that games are not a substitute for books, but a way to help children learn. And if, like me, you grew up playing Fraction Fever (the ROM is here, if you’re an emulator geek) or any of the other Spinnaker titles, perhaps there is some credence to these theories.

There is also this commentary from the 1913 article:

There are many pictures being thrown upon the screen every day which, although not really harmful, possess no merit. Some are positively ridiculous, and portray scenes both unnatural and unreal. It is not to be expected, however, that with the demand for films exceeding the supply every production should be perfect.

It seems to me that Ebert’s Grumpy Old Man routine was published in newspapers a century before. The medium is the only thing that’s different.

Jason Rohrer’s surprisingly touching game, Passage, freely available for download and released a few months ago, quite easily destroys Ebert’s thesis that the video game is incapable of poetry. Rohrer achieves a unique poetry both in limiting the player’s perspective to a 100×16 window and through the deceptively simple manner that he has designed this game for the player. Play the game once and you will follow a strapping young man from left to right. He finds a woman along the way. A pixelated heart soon follows. As the man advances further along this horizontal tableau, he (and his sweetheart) begins to age. He goes bald. As he continues to age, his position on the axis shifts further to the right. Near the end of his life, he is hobbling. Then a tombstone crops up. The End.

Or is it?

The game isn’t limited to left-to-right movement. Play the game again, press the down arrow. and you will find yourself exploring a maze below the top, collecting many stars and stumbling for a way out. But with this simple design, Rohrer has done something very interesting. If you choose to fall in love with your sweetheart, the two of you can only explore certain areas. Because with your partner in tow, you collectively take up a wider space and can only fit into specific territory. If you choose to go through this life solo, then you’ll be able to collect many of the stars denied you and your sweetheart, but you may get lost in the maze and be unable to find your way back to where your sweetheart waits.

If Passage is not quite the video game’s answer to The Waste Land, Rohrer’s poetic game demonstrates that independent developers can in fact use the form in favor of human experience. Rohrer’s lo-fi approach is a welcome response to high-end graphical tentpole operations. I found myself thinking of all the choices I had made over the course of my life and wondered how I would have turned up if I had made slightly different decisions. Contra Ebert, I did indeed find the experience to make me more curious and empathetic about the human condition. (And this would appear to have been Mr. Rohrer’s objective.) This was something that no amount of fragging had inspired.

If all this sounds fishy, well, the game simply has to be played. Like any work of art, it is something better experienced than talked about. And it requires that superannuated naysayers keep open minds.