It didn’t take long for the gutless Washington Post writer Neely Tucker to chicken out on the Henry Louis Gates, Jr. arrest. Beginning his article with the lame certainty of a Duck and Cover film, Tucker wasted no time suggesting that the conformist maxim “Don’t Mess With Cops” was “one of the common-sense rules of life.” Tell that to the 320 people who complained of racial profiling in 2007 to the Los Angeles Police Department, only for the LAPD to report back in April 2008 that not a single case had merit. Tell that to Zakariya Reed, a Gulf War veteran in Toledo who retired from the U.S. National Guard after twenty years of service, and who, like many Muslims and Arab Americans, was interrogated at the Canadian border because he had converted to Islam and because he had changed his name.

There are more truths to be found in this eye-opening ACLU report released last month, which demonstrates that racial profiling is alive and well in the United States. And you’d have to be more sheltered than a stray Samoyed hoping to woo an owner before getting the gas not to know that the color of one’s skin often remains more suspicious to a police officer than hard evidence.

There are more truths to be found in this eye-opening ACLU report released last month, which demonstrates that racial profiling is alive and well in the United States. And you’d have to be more sheltered than a stray Samoyed hoping to woo an owner before getting the gas not to know that the color of one’s skin often remains more suspicious to a police officer than hard evidence.

But if you’re Neely Tucker and you’re a privileged white guy living in “a predominantly white neighborhood” and you cleave to the naive notion that even the bad cops can have their corrupt actions halted by a next-door neighbor, and if you’re “thrilled” to have the police search your entire house without considering that they might be overstepping their authority, then I must ask in all sincerity just how vanilla your understanding of human nature really is. I must ask whether you even have a basic understanding of American history.

The Fourth Amendment’s beginnings, as Leonard Williams Levy’s Origins of the Bill of Rights helpfully informs us, emerged by linking the right to privacy in one’s home with the Magna Carta maxim that a man’s home is his castle. In 1589, a clerk by the name of Robert Beale asked why agents could “enter into mens houses, break of their chests and chambers” and carry off any evidence that they felt like taking home. Beale was the first figure to suggest that the sanctity of a man’s castle applied to everyone. And over the next two centuries, the English propensity for warrantless searches would draw numerous protests.

Here in the colonies, in 1766, the writ of issuance would face protests from Daniel Malcolm, who allowed customs officials to search all parts of his film save a locked cellar and defiantly responded to these efforts with a set of pistols and the threat, “Try it and I’ll blow your head off.” (A crowd had formed. The officials abandoned their quest. Malcolm and the crowd shared the cask of smuggled wine that he had, after al, hidden in the locked room.)

But the writs of assistance, which gave tax collectors a remarkable degree of powers to violate Beale’s egalitarian link between privacy and the sanctity of home, restricted free speech with the case of John Wilkes and were famously derided in a blistering five hour defense by James Otis. The seeds for the Fourth Amendment were sown. But the fledgling federal government wasn’t exactly upholding its principles. To cite one of many abuses that came in the United States’s first decade, in 1777, six Quaker homes were violently violated, with numerous papers confiscated. Legislation, such as Frisbie v. Butler (1787), was enacted to limit any search which there was reason to suspect. This set down the flagstones for “the right of the people to be secured in their persons, houses, papers, and effects,” and the Fourth Amendment’s ratification.

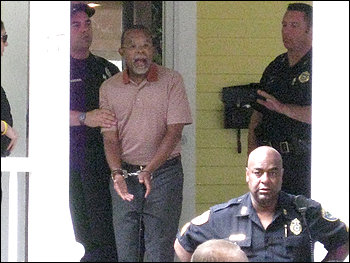

These incidents created an ongoing dialogue — helpful in an emerging nation that valued vital rights and liberties — about what searches and seizures were acceptable. But incidents like Henry Louis Gates’s needless arrest outside of his own home, in which the arrest is motivated by race, the abuse of police power, and police reaction that is incommensurate with the incident being investigated, must likewise cause the dialogue to continue. Gates was fortunate to have the charges dropped, but how many others in this nation don’t have such a luxury?

The complicity of knee-jerk authoritarians like Neely Tucker, who are better suited devoting their limited talents to writing about forgettable two-part TV movies, is part of the problem. It is part of what Martin Luther King once identified as the “almost universal quest for easy answers and half-baked solutions.” Progress begins by identifying a different form of resistance — namely, those who perpetuate grave injustices by endorsing them with their silence. There once was a time when people drank from different fountains or were forced to sit at the back of the bus. And there will eventually be a time in which people will scratch their heads, wondering why the police went around arresting people for irrational reasons.

(Image: Demotix Images)