It became clear on Friday morning at a BookExpo America panel devoted to “Packaging, Positioning and Reviewing in the Fiction Marketplace” that all the VIDA counting and the justifiable grandstanding is getting in the way of building on heartening truths: namely, that women have gained significant (and in many cases dominant) ground as authors, as editorial tastemakers, and as reviewers in the past year.

“I met two of my counterparts,” said New York Times Book Review editor Pamela Paul. “The books editor of the Chicago Tribune is a woman. The Los Angeles Times editor is a woman. USA Today is a woman. People is a woman. New York Magazine is a woman. There are more women book critics than there are men. So that’s kind of the good news, I think.”

Paul picked up a recent issue of the Review and shuffled through the table of contents. “Woman, woman, woman, man, woman.” She claimed that there was nothing deliberate in these review assignments. It was a practice that the previous editor, Sam Tanenhaus, also engaged in. So is there really gender bias?

“I agree,” said Jennifer Weiner. “A lot of it is affinity, not bias.” While commending the rise of women editors, Weiner insinuated a sinister gender bias that emerged from the top. “I think if you gave us the roster of who those women report to, it might sound different. I wonder if they answer, at the end of the day, to men. Does that matter or make an impact?”

Later in the panel, Paul was to correct Weiner, claiming that the Review had full editorial independence. “Not once did Jill [Abramson] or Bill [Keller] ever interfere with my editorial choices.” And while that may be true, it became clear during the conversation that Paul doesn’t really reflect on what her editorial choices mean. Still, I’ll take Weiner’s speculations — even when woefully wrong, such as the notion that men’s reading habits are limited because they are guided by cover design or that people are somehow shamed by what they read on the subway — as a more useful indicator of gender bias than Paul’s high-handed remarks. Because unlike Paul, Weiner was willing to use case examples to bookend her thorny ideological sentiments.

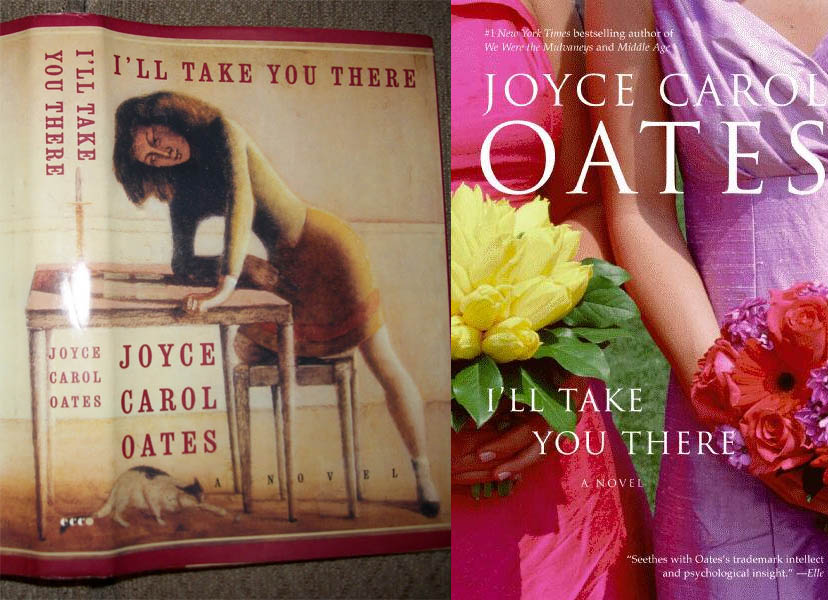

Weiner cited the wildly divergent covers for Joyce Carol Oates’s I’ll Take You There — the Ecco hardcover a striking drawing, the paperback being composed of flowers — as an example of how drastically publishers are willing to alter their covers for women audiences. And she mentioned her own battles with Target, who demanded that the cover for her new book All Fall Down be tinted blue, with the street in Philadelphia considered too gritty for audiences coveting the usual sunny hues.

Weiner cited the wildly divergent covers for Joyce Carol Oates’s I’ll Take You There — the Ecco hardcover a striking drawing, the paperback being composed of flowers — as an example of how drastically publishers are willing to alter their covers for women audiences. And she mentioned her own battles with Target, who demanded that the cover for her new book All Fall Down be tinted blue, with the street in Philadelphia considered too gritty for audiences coveting the usual sunny hues.

“As publishers, you’re working with the availability of images,” said William Morrow Executive Editor Rachel Kahan. She pinpointed one big reason why some of the women’s fiction covers all look the same: the clip art is usually comprised of skinny white yoga models, not regular people. This may account for some of the whitewashing seen on YA book covers and why every book about Africa tends to look the same. When the images used to sell women’s books don’t resemble what’s contained between the covers, much less a reader’s real world, then it seems only natural to ask why we’re still talking about gender balance. The issue is far more complex.

There are still disheartening yet treatable statistics. Moderator Rebecca Mead looked into the gender bias of the New York Times‘s daily reviewers over the course of one year and discovered that it still skewed mostly male: Janet Maslin reviewed 42 male authors and 23 women. Dwight Garner reviewed 43 men and 21 women. Michiko Kakutani reviewed 69 men and 16 women. But the issue is largely a matter of waiting for the old boys to croak (namely, Robert Silvers) and for the VIDA pie charts to include more matching sets of semicircles. [UPDATE: Please see 6/2/14 Update below on the gender ratio numbers. Please see my independent audit reflecting troubling gender parity.]

Covers, said Paul, have never factored into the Review‘s assignments. I already knew this. So I took the liberty of asking a provocative question at the panel’s end, pointing out to a recent Facebook thread which dared to ask, “Large novels (600+ pages) by women whose dominant mode isn’t narrative realism? I can only think of two offhand: The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing and The Making of Americans by Gertrude Stein.” I then cited five literary and/or risk-taking titles that The New York Times Book Review had not reviewed:

- Porochista Khakpour’s The Last Illusion: (publication date: May 13, link to screenshot of NYTBR search showing no results)

- Paula Bomer’s Inside Madeleine: (publication date: May 13, link to screenshot of NYTBR search showing no results)

- Evie Wyld’s All the Birds, Singing: (publication date: April 15, link to screenshot of NYTBR search showing mere capsule)

- Mona Simpson’s Casebook: (publication date: April 15, a review had not been published until this afternoon and I obviously did not see it)

- Cynthia Bond’s Ruby: (publication date: April 29, link to screenshot of NYTBR search showing no results)

Paul claimed, “We’ve reviewed four of the five.” [UPDATE: See 6/14/14 UPDATE below.] But it’s clear from the evidence that she was either lying through her teeth or is now so hopelessly slipshod at her job that reviews of books that aren’t huge will never run on a timely basis. That would certainly fit the Review‘s abominably dilatory standards for two National Book Award winners: Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones (published August 30, 2011, reviewed December 30, 2011) and Jaimy Gordon’s Lord of Misrule (published November 25, 2010, reviewed by Maslin and profiled by Chip McGrath, but never reviewed in the NYTBR). I mentioned these two names. Paul brushed it off.

I asked what could be done to encourage more wild, edgy, and ambitious literature from women? Books from outsiders. Ambitious books written by women that can be included, now that women are, thank the heavens, storming the gates. For this, I was informed later on Twitter that I was insulting. An amental agent, whose superficial sensibilities are writ large in her most recent sale (“a guidebook for those of us who can’t afford diamond encrusted pacifers or superyachts but still aspire to our own version of the glamorous life”), also misquoted and condemned me as a moron:

And the Women’s Media Group suggested that I was oppressing the room with my loud voice:

The mystery of plentiful 600 page novels written by women and not rooted in realism — one that I’d actually like to know the answer to, which is why I bothered to ask it — remains unsolved. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah was offered. (Sorry, it’s 496 pages.) And so was Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries, which many in the Facebook thread insisted did not count. The reason I asked the question was not to suggest that women couldn’t write ambitious novels, but to get people to consider why women aren’t allowed to. As this Wikipedia list of longest novels points out, only Ayn Rand and Madeleine de Scudéry have been permitted doorstoppers. And I’m hardly the only one ruminating on this.

But the goal is no longer to have challenging discussions, to consider opposing points of view (or even the strange exotic men who enjoy reading both Weiner and Knausgaard), or to ask uncomfortable questions. The goal of organizations like the Women’s Media Group and people like Pamela Paul is to drown out the outside voices because they’re too busy congratulating themselves over opinions and sentiments they’ve already made their minds about and have no intention of changing. But I do want to thank Rachel Kahan, who made an attempt to address my question after the stunned hush, Jennifer Weiner (who has always listened to my loud voice with respect), and Rebecca Mead, who was a good moderator. These three women understood that I was not the enemy. I’m not so sure about the other ones.

[6/2/14 UPDATE: I’ve been informed by a reader that the gender ratio numbers from the three New York Times daily book reviewers were incorrect. I have performed a full and detailed independent audit (links to all reviews and methodology are provided in article) for the period between June 1, 2013 and May 30, 2014. The breakdown is as follows: Dwight Garner — Male Authors: 45.5 (65.9%), Female Authors: 23.5 (34.1%); Michiko Kakutani — Male Authors: 37.5 (69.4%), Female Authors: 16.5 (30.6%); Janet Maslin — Male Authors: 68 (68.7%), Female Authors: 31 (31.3%).]

[6/14/14 UPDATE: Two weeks after the panel, two more reviews of the five books that I cited to Pamela Paul appeared in the June 15, 2014 edition of The New York Times Book Review: Paula Bomer’s Inside Madeleine was reviewed by Dayna Tortorici and Evie Wyld’s All the Birds, Singing was reviewed by Malie Meloy. This brings the total up to three books, out of the “four out of five” claim Paul uttered at the panel. While I approve of these coverage decisions, this nevertheless brings up another sizable problem at the NYTBR: the tendency for reviews to run quite late after their publication dates. I will take up this issue with hard data in a future post. Pamela Paul continues to refuse to discuss these issues, as does public editor Margaret Sullivan. I stand by my “mendacious” charge until Paul produces a fourth review.]

Weiner cited the wildly divergent covers for Joyce Carol Oates’s I’ll Take You There — the Ecco hardcover a striking drawing, the paperback being composed of flowers — as an example of how drastically publishers are willing to alter their covers for women audiences. And she mentioned her own battles with Target, who demanded that the cover for her new book All Fall Down be tinted blue, with the street in Philadelphia considered too gritty for audiences coveting the usual sunny hues.

Weiner cited the wildly divergent covers for Joyce Carol Oates’s I’ll Take You There — the Ecco hardcover a striking drawing, the paperback being composed of flowers — as an example of how drastically publishers are willing to alter their covers for women audiences. And she mentioned her own battles with Target, who demanded that the cover for her new book All Fall Down be tinted blue, with the street in Philadelphia considered too gritty for audiences coveting the usual sunny hues.

Correspondent: But not every man, Faye, is going to sit down and slap thousands of dollars wanting to get laid like this.

Correspondent: But not every man, Faye, is going to sit down and slap thousands of dollars wanting to get laid like this.