It doesn’t matter if some generous groomsman (or bridesmaid) has plied me with good scotch or not. It doesn’t matter if the DJ or the band has the musical taste of a humorless military historian who blasts nothing more than John Phillip Sousa. If you encounter me at a wedding, chances are that you will find me dancing. There seems to be no better way to celebrate the union of two than putting two feet together. Very often, I will have no clue as to how I began dancing. Sometimes it will start with a trip to the men’s room. Upon relieving myself and washing my hands, I will often return with some terpsichorean fervor that astonishes the other wedding guests. I will dance with anybody. Grandmothers. Kids. Other men. I have been known to corrupt small children with some of my more libidinous moves, whereby I swing an invisible lasso around another man’s neck and proceed to rope him in, concluding my cowboy allemande with a rakish leer which suggests that I will be taking my partner to an indecent location. I have seen kids reproduce these moves.

What does any of this have to do with Morning Glory? Well, somewhere within this watered down Broadcast News knockoff is a mild audience-friendly satire screaming to cut the rug. Last week, with Due Date, we saw how director Todd Phillips and his co-writers managed to update the Planes, Trains, and Automobiles template into an enjoyable comedy that still had the smarts to include some dark observations about our present age. Morning Glory – with its egotistical anchors, its rider-mandated fruit platters, and its accidental caption beneath Jimmy Carter’s photograph – has a few promising steps. But it is too often that stiff partner that lacks the courage to get up and go, to take more than a few perfunctory chances. It is a movie in desperate need of some hip-shaking and a hip flask.

Rachel McAdams plays Becky Fuller, a television producer who foolishly believes that the Protestant work ethic still applies in the television industry. She longs for some higher rung because she has toiled for many years (sans boyfriend, sans many friends aside from her co-workers) as an assistant producer on the morning show, Good Morning, New Jersey. The big boss asks her in for a big meeting. And Becky thinks that she’ll at last land that promotion. Wearing a YES, I ACCEPT tee beneath her clothes, Becky is shitcanned instead. She then spends the early portion of the movie trying to land a job, with her chirpy go-go energy lacking Holly Hunter’s can-do spunk in Broadcast News. It’s really more of a fey merge between Hunter and a mid-1990s Renee Zellweger. Becky is so desperate to be liked that she is very often channeling the needy qualities contained within Aline Brosh McKenna’s script.

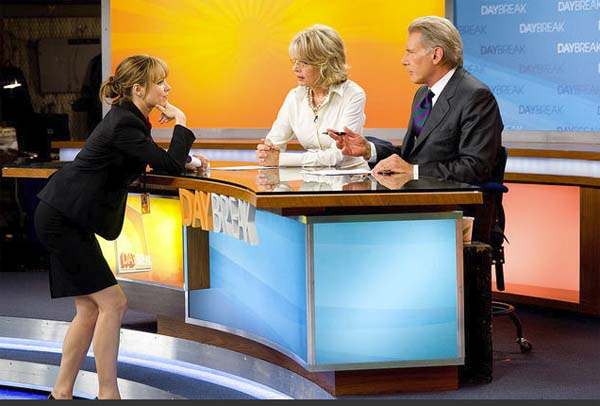

She somehow talks her way into a job as executive producer at Daybreak, a network morning show in last place. Becky must endure dull segments about weather vanes, sleazy reporters who wish to take photos of her feet, and a staff that expects Becky to fall through the revolving door. Certainly, the audience is inclined to sympathize with the Daybreak staff. McAdams’s relentless peppiness is, at times, a liability to our willingness to believe in the movie. One does not occupy a top perch in the media world without giving a few orders to ice the unruly subordinates. And while Becky does deliver at least one such ruthless move, we’re never entirely convinced that she has the organizational chops to keep this show together.

Becky places her faith in the aptly named Mike Pomeroy (Harrison Ford), a respected journalist with Pulitzers and Emmies in his closet who lost some vital television spot some years ago. Alas, he’s referred to as “the third worst person in the world” among some former co-workers. Still under contract to the network, Becky installs Pomeroy as Daybreak co-host. The big joke here is that Pomeroy would rather use words like “abrogate” on air or report on serious news stories rather than remark on Easter bunnies. While there’s some late stage conflict between Ford and McAdams, the comedy is hindered by Ford’s terrible performance. He shamelessly overacts in his part: widening his eyes, pointing his index finger, and barking his lines with a sad “Get off my plane!” gusto that transforms a chief character into a regrettable cartoon. It’s sad to remember that Ford was once an actor capable of great control in Frantic, Witness, and The Mosquito Coast. (On a positive note, I can report that Diane Keaton is wonderfully controlled, as always, as the grumpy host who has been on the show too long.)

The movie is most effective when it drifts away from its obvious inspiration. When McKenna and director Roger Michell comprehends that Rachel McAdams is not Holly Hunter, that Harrison Ford is not Jack Nicholson, that Patrick Wilson (McAdams’s love interest, whose receding hairline and look resembles William Hurt in 1987) is not William Hurt, and the guy with the half-grown facial hair playing McAdams’s producer who I’m too lazy to look up on IMDB is not Albert Brooks. (Sorry, guy with the half-grown facial hair playing McAdams’s producer. I had to turn around this review fast.) James L. Brooks certainly never needed a live camera capturing a reporter screaming while he rides a rollercoaster or howling in pain when getting a tattoo buzzed into his flesh. But our present epoch of reality television and YouTube does requires such moments.

It’s too bad that this promising satirical thrust couldn’t extend to the rest of the film. There are worse films than Morning Glory out there. But McKenna and Michell don’t seem to know that there was this writer named Ben Hecht and this director named Howard Hawks, and these actors named Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell, and this talent all came together and created an indelible comedy, with the dialogue gunning at a .45 Thompson’s pace. They can’t recall that we remember that film so well seventy years later because Hawks had the wisdom to swap gender roles from the original source (the play The Front Page), with Hawks agonizing over the casting. I have to wonder: Who will remember Morning Glory seventy years from now? What might have happened if McKenna and Michell had the courage to defy their straitlaced obligations and dance?