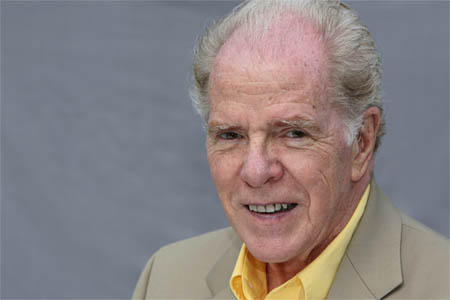

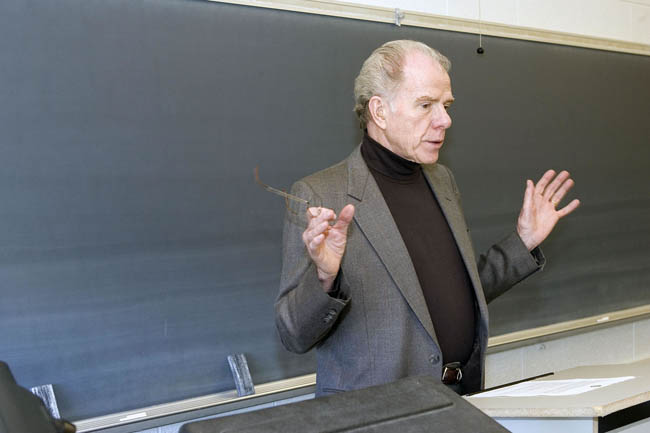

William Kennedy appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #427. He is most recently the author of Changó’s Beads and Two-Tone Shoes.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

For related material, you can read my Modern Library Reading Challenge essay on Ironweed.

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Caught in a migratory comedy of errors.

Author: William Kennedy

Subjects Discussed: Resonances in historical fiction that align with the present day, the William Gibson notion (“The future has already arrived. It’s just not evenly distributed yet.”), Guantanamo Bay and waterboarding, the 2008 Greek riots, writing Ironweed while being firmly immersed in the 1930s, referring to the homeless before “homeless” existed as a word, prophetic novelists, Bernard Malamud’s The Fixer, the tradition of torture, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Roscoe, writing about the Albany political machine for forty years, stolen elections and kickbacks, interviewing morally shady figures as a novelist and as a journalist, meeting with Charlie Ryan, Dan O’Connell, how Kennedy coaxed political figures to tell him stories over the years, sources who insist on being on the record as insiders, intrusive noise, the journalist as the intellectual equivalent to the bartender or the barista, politicians who talk differently when microphones are present, Newspaper Row in Albany, lead filings and rats descending from newspaper ceilings, journalistic squalor, Kennedy’s relationship with Hunter S. Thompson, Pulitzer’s notion of journalism, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, fiction vs. journalism, The Ink Truck, Fellini, how a multidimensional fictitious form of Albany sprang from extremely devoted research, writing seven drafts of Legs, invention and informed speculation, the importance of letting imagination settle, Legs‘s resistance to realism, structuring a novel on The Tibetan Book of the Dead, discovering newness as a writer, precedents for Ironweed, parallels between Cuban history and civil rights, efforts to find the right Cuban history period for Chango’s Beads, Fulgencio Batista’s kids going to school in Albany, the “Circe” chapter of Ulysses as a possible inspiration point, The Gut in Albany, Black Power and community action during the late 1960s, Stokely Carmichael, Malcolm X sitting in the balcony of the New York Senate, Eldridge Cleaver, the Albany Cycle beyond 1968, telescoping Albany history for the sake of telling a story, arson and riots, the figure of Matt Daughterty, having to publish newspaper stories in out-of-town newspapers to avoid the wrath of the Albany political machine, comparisons between Quinn’s Book and Chango’s Beads, following personalities contained within fictitious families over many years, journeys away from Albany in the Albany cycle, avoiding Albany burnout, a new play based on a departure from Very Old Bones, and fiction driven by bullet-like dialogue.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: We were drawing a distinction between the journalist who is the bartender or the barista — the intellectual equivalent to that — and the novelist, who may in fact have an even greater advantage. Some novelists who were former journalists have told me that they’ll get people to talk with them more if they say they’re a novelist. I’m sure this has been the case with you.

Kennedy: Oh yeah. When the Mayor invited me over to talk about writing a book with him, he didn’t say quite why. I couldn’t understand it. Because I thought he had great antipathy toward me. But I went over. And we just had this conversation. And I sat there and talked to him. And I took a lot of notes. And he said he wanted me to maybe interview him and dredge up whatever I wanted to and write whatever I wanted to. And then he would rebut it. And I didn’t think that was going to work. But I knew that it was a great opportunity to talk to the Mayor.

So anyway we carried on. And it turned out I did write a lot about him in this book. It was kind of a biography. I wrote three pieces actually on him. And he was great in the first meeting. And then the second time, I brought over a mike and a tape recorder. And he clammed up. I mean, he didn’t stop talking, but he didn’t say anything. I mean, he was very salty in the first conversation. And he was a very intelligent man and very well-educated and smart as they come politically. And he had a great sense of humor. But it was boring in the second interview. So I took him out again. I took him to lunch. And he opened right up again as soon as he knew there was no tape recorder. And I took notes. He’s safe with notes because he can say, “He got it wrong.” There’s no proof.

Correspondent: Well, I actually wanted to ask — speaking of history, there are moments in Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game and Quinn’s Book where you have newspapermen who are wearing hats as the lead filings are falling upon them. In the case of Billy Phelan, there’s actual rats falling from the ceiling.

Kennedy: That’s true.

Correspondent: I’m curious. Did you have first-hand experience of this?

Kennedy: No. This was at the newspaper that I was working on. But in their previous incarnation, which was only a few years before I got there, they were on Beaver Street in a very old, old center of the city. The South End. In The Gut. And it was Newspaper Row. The Albany Journal was there. The Albany Argus. The Knickerbocker News. The Knickerbocker Press. Etcetera etcetera. The Times Union was up the street a bit. And then they moved into new digs. But I remember that one of the reporters and the copy editors said that the rats used to come down, walk the ceiling. The composing room was upstairs. Over the city room. And there was always these lead filings that were coming through the cracks in the floor. And so these guys wore their hats around the desks. And the reporters wore their hats indoors.

Correspondent: The pre-OSHA days. (laughs)

Kennedy: You know, it had a practical application, those hats. In addition to being the style of the day. And the rats used to come down and eat the paste out of the paste pots.

Correspondent: Which is also immortalized in Billy Phelan.

Kennedy: That’s in Billy Phelan. They were all stories that these guys who had grown up there, they’d seen it. One of my buddies, he’d been a reporter for ten years or so all during that period in Beaver Street. And he was a great storyteller. And he told me…well, you know.

Correspondent: Did you experience any first-hand journalistic squalor?

Kennedy: Journalistic squalor.

Correspondent: Along those lines. Or perhaps other forms of squalor.

Kennedy; (laughs) Well, no. Not quite like that. The paper had modernized. I mean, I was there in the age of the typewriter and the clacking teletypes and papers would stack up on the floor like crazy. At the end of the work day, everybody threw everything onto the floor. The old newspapers. All the old teletypes. And it was a great mess. There was….hmm, squalor. (laughs)

Correspondent: Rotting walls? Asbestos-laden environments? (laughs)

Kennedy: Sorry, I can’t. I knew all the guys who had gone through it.

Correspondent: Well, on a similar note, Hunter S. Thompson. I have to ask this largely because The Paris Review interviewed you and cut this bit. He said, “He refused to hire me. Called me swine, fool, beatnik. We go way back.” But I also know that he wrote you a quite hubristic letter. How did you two patch things up after this early exchange of invective and all that?

Kennedy: Well, I never called him a swine.

Correspondent: (laughs)

Kennedy: It’s possible in a letter, in later years, I might have called him a swine. But that was his terminology.

Correspondent: He was trying to prop you up.

Kennedy: I would just throw it back at him or something like that. You know, there was no rancor at all. After the first exchange of letters, almost immediately it was patched up. I mean, he was furious at me for rejecting him when he applied for a job. You’re talking about the quote there where he said…

Correspondent: He said that on Charlie Rose.

Kennedy: Charlie Rose. But he was referring to my attitude toward The Rum Diary. Which was the novel that he was writing down in Puerto Rico when I got to know him. And he had just started it. And in later years, he sent it to me. I wish I had kept it. I don’t know why. I can’t find it. I don’t think I have any remnants of it and I’ve got a lot of his stuff. But maybe I have some pieces. But I don’t remember. And I can’t even remember the letter I wrote. But I wrote him a letter and I told him, “Forget about this novel. You can’t publish this. This is terrible.” And it was a big fat novel. It was fat and it was logorrhea. And it was a young man’s ruminations and discoveries of all of that.

Correspondent: A journalist aspiring to be a novelist.

Kennedy: Right, right, right. And he was a smart guy. Very, very smart guy. But that novel just didn’t work. What was published — the book that was published is one third of the text of the old book. It doesn’t have any of those flaws that I could see — I just started to read it again the other day. I tried to see the movie three times, and I can’t.

Correspondent: Oh really?

Kennedy: Well, I’m in the Academy and I get these screeners from the Academy. But it didn’t work. The screener didn’t work. It says “Wrong disc.”

Correspondent: Oh no.

Kennedy: So I have to get another one. But I’m anxious to see it. I think it’s full of probably libelous accusations against the [San Juan] Star, the newspaper down there and the people who run it. But that was expected from Hunter.

Correspondent: What do you think distinguishes your approach — being a journalist turning into a novelist — from Hunter’s approach? I mean, was he just not serious enough and you were more devoted? Was it a matter of being well-read? What was it exactly that distinguished the two of you?

Kennedy: Well, I was a serious journalist. I mean, he presumed to be. That was the basis for our initial argument about that bronze plaque. You know about that? The bronze plaque on the side of The New York Times — it’s a quote from Joseph Pulitzer When that building was home to The New York World, a great newspaper that Pulitzer ran in New York. Anyway, he revered that. You know, it’s this high-minded attitude toward the news. No fear of favor or whatever. Work against the thieves. Whatever. I’ve absolutely forgotten what Pulitzer said.

[Note: The Pulitzer plaque reads: “An institution that should always fight for progress and reform, never tolerate injustice or corruption, always fight demagogues of all parties, never belong to any party, always oppose privileged classes and public plunderers, never lack sympathy with the poor, always remain devoted to the public welfare, never be satisfied with merely printing news, always be drastically independent, never be afraid to attack wrong, whether by predatory plutocracy or predatory poverty.”]

Kennedy; I remember its tone. And I could find it. And this whole episode is summed up in the introduction to Hunter’s book, The Proud Highway — his first collection of letters. He asked me to write an introduction to that. And I told the whole story of how he applied for the job and didn’t get it and so on. But his attitude toward journalism was high-minded. But when he started to practice it, a year or so later, roaming around South America, he started writing — he was winging it, you know? He wasn’t interested in “Just the facts, ma’am.” He was half a fiction writer in those days. Roaming around. Whatever caught his fancy or his imagination, he would write it. I mean, it came to a point where he went to the Kentucky Derby and that was the one that really put him on the map. “The Kentucky Derby is decadent and depraved.” It ran in Scanlan’s Monthly, I think. And it had nothing to do with reporting. He was making it up. And it was fiction.

There may have been some basis in all that happens in the story for it. But he just invents the dialogue that goes on between the various people and follows his own chart and reacts as a novelist, and then presents it as journalism. This is what Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was presumably journalism. But it’s fiction. It’s a novel. And he claimed in retrospect that he had notes to prove every element in that novel. But he didn’t. (laughs) I mean, all the hallucinations. Whatever his hallucinations were, they were hallucinations. And they’re his. And they’re internal. And who’s to say who’s hallucinating when he’s writing what he’s writing. The sum and substance of Thompson was that he started off as a journalist and he became this wild crazy gonzo journalist, which was half a fiction writer’s achievement. And he was always in the early days thinking about the novel and new forms of the novel. And he created one. Novels are very valuable in their wisdom and their insights and their reporting and their historical penetration of the world that they’re centering on. And he was famously talented in all those realms to achieve those things. And he did. But in the end, I mean he comes off as a career journalist and a singular one. There was nobody like him and there never will be. A lot of people have tried. He’s inimitable. But when he started out, he had all the baggage that goes with the aspiring novelist. And he always made the distinction that I started off to be a journalist and turned into a novelist and he started off to be a novelist and turned into a journalist. And that’s true enough.

My journalism very rarely could be challenged — it could never be challenged as a work of fiction. I never did anything like that. I found ways to enliven the text with language. So did Hunter. But Hunter also reimagined history and reimagined daily life when he invented his world.

Correspondent: To go to your work, The Ink Truck — I wanted to ask you about this. Your first published novel. This is interesting because, unlike the topographical precision that you see in the Albany Cycle, the details of Albany in The Ink Truck are not nearly that precise. They’re more abstract. And I’m curious why that sense of place only emerged in the subsequent novels.

Kennedy: Well, because when I wrote that novel, I was reacting to my resistance to traditional realism and naturalism. You know, I had been there with Steinbeck, Dreiser, James T. Farrell, and so on. And Hemingway also was a great realist. Not the naturalist, but the great realist and the great reporter. And I was in a different mode. I was immersed in Joyce at that time and very much aware of Ulysses and the wildness of the invention that pervades that novel. I was thinking of the surrealists. I was in the grip of Buñuel the filmmaker. I loved his work.

Correspondent: Also a wonderful late bloomer too.

Kennedy: (laughs) And Fellini. I though that 8 1/2 was one of the great movies ever made. It may be the greatest to me and I’m not sure I don’t think that still.

Correspondent: What of Satyricon? (laughs)

Kennedy: Well, I thought it was interesting. So much of Fellini I do love. But 8 1/2, because it was in one guy’s head and it just went in and out of reality, that’s what I wanted to do. I used to say that novel was always six inches off the ground. So levitating was important. And I wasn’t really interested in grounding myself in the squalor of that situation. That was a pretty squalid time when we were in the guild room during that strike. There was a strike that I went through and was the inspiration for that novel. But that book is sort of an excursion to comedy and surreal comedy. I mean, it presumes to be serious in certain stages of its intensity. But basically it’s a wild, crazy, surreal story.

Correspondent: But when you have the character of Albany begin to appear in your work, suddenly I think there’s more of a kitchen sink approach. You have very hard-core realism. You have hallucinations. Surrealism. You have all sorts of things. Almost a kitchen sink approach. And I’m curious if the increasing complexity of your books, where this comes from. Does it arise out of your very meticulous and fastidious research? Does it arise from wanting to reinvent the form of the novel? To not repeat yourself? Does it arise from having established a Yoknapatawpha-like universe of characters? What of this?

Kennedy: Well, all of the above. Everything you said. I was always trying to do something that I hadn’t done before, that I couldn’t attach to anybody in particular. You know, you can’t imitate Joyce. You can’t imitate Hemingway. I tried and I did all the way along in various failed enterprises. And I knew that it was a dead end. I was trying for something new. With Legs, I was inundated with research. I spent two years under the microfilm machine. We no longer have to do that. Just punch in Google. Now it’s amazing. But in those days, I would spend days. All day. Half the week inside the library. Not only microfilm, but all the books of the age. All the magazines. I went to New York and got the morgues of all the major newspapers. The Times. The New York Post. The Daily News, which was fantastic. And so on. And I researched everything there was to find on Legs Diamond serendipitously. And then I also kept turning — I probably interviewed 300 people. I don’t know how many. Sort of cops and gangsters. Retired gangsters with prostate trouble. And I really stultified myself at a certain stage in that novel. And I had to stop and take account of what was really going on. And I had to reinvent the book.

Correspondent: You wrote it seven times, I understand.

Kennedy: I guess the seventh was the final time. I wrote it six times. Or was it six years and eight times? The eighth time was a cut. I had finished it but it was too fat. So I cut 70, 80 pages. I don’t remember what I cut. But I don’t miss them. Whatever I cut, it was all right. But I started from scratch really. After six drafts, I went back and spent three months just designing the book all over again and designing history of every character all over again and putting a totally new perspective on it. Because I had too much material. And there was no way to stop it from coming to me. Except to just close it off and say, “I’m not going to read another newspaper. I’m not going to crack another book. I’m going to write the story. I’m done with the research.” Of course, that never really happens. You have to go back and check. But that’s what I did. And that’s how I finished the book.

The Bat Segundo Show #427: William Kennedy (Download MP3)

(Image: Judy C. Sanders)

William Kennedy was in his mid-fifties when all of his novels went out of print. While he remained a working journalist, his latest manuscript about a scuffed up drifter named Francis Phelan — a minor character from his 1978 novel, Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game — had been rejected by thirteen publishers. Ironweed had come comparatively quicker than his previous novels. Kennedy wrote eight versions of Legs over six years. He devoted two years to Billy Phelan. But he wrote Ironweed in seven months. Still, this unanticipated celerity was of null solace to publishers studying Kennedy’s then sketchy sales record.

William Kennedy was in his mid-fifties when all of his novels went out of print. While he remained a working journalist, his latest manuscript about a scuffed up drifter named Francis Phelan — a minor character from his 1978 novel, Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game — had been rejected by thirteen publishers. Ironweed had come comparatively quicker than his previous novels. Kennedy wrote eight versions of Legs over six years. He devoted two years to Billy Phelan. But he wrote Ironweed in seven months. Still, this unanticipated celerity was of null solace to publishers studying Kennedy’s then sketchy sales record.