“He said that, as a literary biographer, he’d been asked to talk about Peter’s literary interests, which of course was absurd in a mere seven minutes: Peter deserved a literary biography of his own, and maybe he would write it — anyone with stories to tell should see him afterwards, in strictest confidence, of course. This got a surprisingly warm laugh, though Rob was unsure, after what Jennifer had said, whether he was sending himself up as a teller of other people’s secrets.” — Alan Hollinghurst, The Stranger’s Child

In more than a decade at New York Magazine, Boris Kachka has displayed a limitless knack for bumbling inquiry, suggesting an easily played and incurious rube who hopes and believes with every desperate palpitation of his hypoplastic heart that constant proximity to disinterested players will reveal some grand Talmudic truth.

Kachka is a “reporter” who has seen faux import in an osteoporosic Sally Field climbing fourteen flights of stairs in a midtown hotel. Mere months before Romina Puga, Kachka bombarded Jesse Eisenberg with vapid invasive questions, attempting to read sage significance in Eisenberg’s monosyllabic discomfort and leading one to wonder if Kachka had written his superficial queries on his palm in some headlong campaign to read the future. In April, Kachka visited Claire Messud and James Wood and, unable to spark it up with these two charming and gracious minds, littered his simpering copy with eight desperate New Journalism “[BARK!]”s (one sans brackets) and dwelt more on Wood’s mien than his thoughts.

At New York, Kachka established himself as a diseased mongrel who could barely push his debilitated legs off the porch to work his beat. He has littered his work with portentous phrases like “anomie of Lipsyte’s generation” and “Park Slope’s popular freelance perch,” and it all smacks of a desperate burnout raiding the low-hanging lexical fruit that hadn’t already been plucked for some “Talk of the Town” piece at a more august publication.

Kachka’s new book, Hothouse, comes out on Tuesday and purports to chronicle Farrar, Straus & Giroux with all the lapel-grabbing furor of Jacob Riis investigating the New York slums. Despite “more than 200 interviews,” the result is a dry, listless, tendentious, sexist, blinkered, and preposterous book which regurgitates insignificant facts, latches onto third-hand rumors, and fails to comprehend the way the publishing industry really works.

Yet Kachka’s insufficient history has inexplicably captured the imagination of a few gullible and unquestioning boosters, including Heller McAlpin at the Los Angeles Times and Carolyn Kellogg at Bullseye. Perhaps Hothouse has received a fair pass because journalistic standards have collapsed well beneath the lowest notches on the limbo bar. Or maybe these literary cheerleaders cannot comprehend that hearsay, which is impermissible testimony in a courtroom, is not acceptable in any work purporting to reveal the trajectory of an uniquely influential business.

Much like Leonard Zelig or, perhaps more accurately, Being There‘s Chauncey Gardner, Kachka has been allowed to commit solecisms for years, yet there’s an inexplicable hubris attached to his bungling, the telltale traits of a more famous Peter Sellers character. Kachka’s approach to the truth involves relying on inference without respect for person or underlying fact. Helene Atwan, now the Director of Beacon Press, leads Kachka to believe that FSG intended to change Peter Høeg’s last name to “Hawk” for the release of Smilla’s Sense of Snow, and Kachka laps this confabulation up so that he can grill Roger Straus III on this incredulous matter. Kachka specializes in the bold uncorroborated inference, writing like a man who isn’t getting any action at home: “By the early 1960s, [Roger Straus] was probably sleeping with three of his female operators.” Probably? The scuzziest TMZ reporters are more committed to accuracy. (There are, of course, no endnotes upholding this claim.)

If Kachka feels as if his subjects aren’t giving him the answers or the access that he believes he is entitled to by rightful decree of the tottering authority in his feeble delusional mind, or the quotes don’t match the story he believes he already knows, then he will burn them with his cheap prossy pen. Here, for example, is Kachka’s first description of Jonathan Galassi in Hothouse:

Galassi, on the other hand, is a patrician only by training, a bon vivant only by necessity, but a nerd through and through. He invited his fourth-grade teacher to his ninth birthday party. He seems to have learned the bold body language of an alpha male, but never quite vanquished his low, slightly nasal voice or downcast expression.

Instead of being curious about Galassi’s intriguing background, Kachka sees Galassi as a cartoon to be mocked. Kachka cannot be arsed to get his source to trust him. He is clearly not Richard Ben Cramer talking baseball with George W. Bush to get a stubborn man to open up. And stacked next to fellow New York journalist Robert Kolker (author of the recently released and well-received Lost Girls), he’s a total embarrassment, especially when he pursues an Oliver Stone-like trail suggesting that Straus had a secret telephone line and was working for the CIA. Had Kachka more time to push his plodding connections, he most certainly would have spotted Straus on the grassy knoll.

Like the despicable gossip peddler Paul Bryant in Alan Hollinghurst’s excellent novel, The Stranger’s Child, Kachka seeks any vaguely salacious angle to throw into his preordained template, whereby FSG is a “sexual sewer,” male employees fuck anything that moves, and Mad Men parallels snap into place like a smooth sudoku puzzle. In Hothouse, Kachka claims that, because someone may have seen long black strands of hair in a borrowed apartment, Susan Sontag and Straus were having an affair. He then spends the majority of his book calling David Rieff “an illegitimate son” to shove this unsubstantiated carnal connection down the reader’s throat. When Kachka finds former FSG assistant Leslie Sharpe, who tells him, “Everybody was fucking everybody in that office,” the reader feels the extremely unsettling aura of Kachka’s cock hardening at the news. But of course, Kachka has nothing reliable in his notes on the many affairs he claims went down. Any man close to the age of forty who wags his dry tongue for scuttlebutt scraps is a pathetic figure indeed.

Hothouse evinces how little Kachka understands wealth by pointing to “starter dachas,” opens chapters with journalism cliches (“If Jonathan Galassi didn’t exist, FSG would have to invent him”), and squeezes out strained efforts at Tom Wolfe-style savaging against agent Andrew Wylie:

It doesn’t help that his face tapers from a broad bald pate to an unshaped brow, icy eyes, and a chiseled, lupine chin, or that his laugh sounds like that of the world’s most cultured hyena.

Can a face taper? Is Wylie a hyena, a wolf, or a jackal? Given all the mixed metaphors, I don’t think Kachka even knows.

Kachka lacks one of the competent reporter’s primary skills: pretend to like a source you loathe (or, more ideal, find something to like about someone you despise). He’s long past the point where any true observer can feel sorry for him, although the pity blurbs accompanying his cotillion ball reveal a few noteworthy mensches who should be commended for their kindness. Still, Kachka is not significant enough to be put out of his misery with a pink slip and a peremptory blast in the human resources office. He trudges on, a bearded penguin known to harass people with multiple phone calls at 6 AM (including yours truly many years ago on a matter pertaining to Zadie Smith) and getting people so thoroughly wrong that one wonders if he has even read Philip Roth’s American Pastoral.*

Roth, like John McPhee and Edmund Wilson, was wooed by FSG without an agent. An assiduous journalist would look into whether or not Roger Straus, a notorious cheapskate (a man who operated FSG from a ramshackle Union Square West headquarters for years and a man who did not contribute a sou to Susan Sontag’s breast cancer fund), actively pursued writers who did not have representatives to protect their interests. (Kachka points out that Straus sought to discredit agents wherever he could, but he isn’t robust enough to construct a timeline or a concrete set of governing principles.) Given the sour grapes that developed between Straus and Wylie in the 1980s, to say nothing of the resentment expressed by writers for being underpaid, it is palpably obvious to look into the very business philosophy that permitted a publisher, often sustained by family wealth when times were lean, to subsist as long as it did. It would also seem natural to focus on how New Directions, who worked in the same building as FSG for many years, operated as FSG’s competitor, snapping up the poetry of Thomas Merton and John Berryman before FSG editor Robert Giroux.

Hothouse reveals that Straus was a poor businessman (“No FSG catalog would be complete without its impending announcement,” mocked one wag about the publisher’s long delayed titles), even as it promulgates the false myth that this apparent patriarch had “just enough of a personal financial cushion to keep from falling over the brink.” Nearly 250 pages later, Kachka writes, “The fact is that 1988-vintage FSG could have eaten 1982 FSG for lunch. In the old days, the cash simply hadn’t been there. Roger’s cheapness may have been inborn, but it was refined by forty years of hard, break-even experience.” Or maybe it wasn’t. Kachka is such an otiose journalist that he doesn’t follow the money, except through mere conjecture. He claims that Wilson, Sontag, Carlos Fuentes, Tom Wolfe, and Joseph Brodsky “received financial support far beyond standard contracts,” but provides neither source nor sums for this claim. Why did Straus really sell his townhouse? Is it not possible that Straus sold FSG to billionaire Georg von Holtzbrinck in 1994 because his coffers were light? Kachka lacks the diligence to pursue these questions, in large part because it contradicts his cheap thesis that FSG is the Greatest Publisher of All Time. On the other hand, Kachka is to be commended for inadvertently reminding us that Melville House’s Dennis Loy Johnson, arguably the most hypocritical man working in publishing today, is desperately trying to be a Roger Straus for the 21st century and will surely fail if he continues along the same trajectory.

Kachka does account for Straus’s tendency to skim his titles, but is too much of a milquetoast to probe: “The most common theory, especially among those who saw him lug manuscripts up to Purchase for the weekend, is that he didn’t so much read books as ‘read in’ them, as he sometimes put it — enough to get a nose for them, like fine wines.”

Hothouse is plagued by other contradictory assertions which quickly out Kachka as a squirmy journalist who cannot be trusted. He claims FSG as an innovative publisher, but confesses that Robert Giroux was not an especially edgy editor:

But though he was still approaching the peak of his professional power, he was no longer, if he ever really had been, at the vanguard of taste. By the sixties, even the Beats — most of them too extreme for Giroux — were old hat.

In other words, FSG was hoary from the get go. And it took careful line editors like Lorin Stein, progressive-minded editors like Sean McDonald, and gutsy publicists like Jeff Seroy to turn it into the publisher it is today. But all that happened under a German congolomerate’s watch, not Straus’s.

But what ultimately makes Kachka such an unpardonable scumbag is the way in which he wallows in the very sexism he tries so hard to expose. Aside from perpetuating a fantasy that publishing was a “gentleman’s profession” with “Roger and his publicity girls,” Kachka undermines Margaret Farrar (along with her barely mentioned husband), claiming that the woman who created most of the rules governing crossword puzzle design merely “enriched one publishing house.” (Later, Margaret is dismissed as “the crossword-puzzle creator and sometime editor.”) He introduces FSG supplies manager Rose Wachtel as “a prematurely elderly-looking woman.”

Peggy Miller, Roger Straus’s secretary of several decades, tells Kachka that she refuses to answer questions about whether or not she was romantically involved with her employer. But that doesn’t stop Kachka from deracinating her dignity by suggesting that she’s “a living homage to Straus” and claiming that she and Straus were a “couple,” with rampant fucking during their annual trips to the Frankfurt Book Fair. (Compare this with Ian Parker’s 2002 description of Miller as “a tall, chic, ironic woman.” In fact, save yourself the $28 on Kachka’s junk and just subscribe to The New Yorker to access Parker’s piece.)

The most prominent example of Kachka’s sexism is his deplorable depiction of Jean Stafford, a distinguished (if troubled) FSG writer. Kachka pits her husband Robert Lowell’s accomplishments over hers and has no sympathy for her nervous breakdown even as he points out that Lowell and Gertrude Buckman “spent unsavory amounts of time together headed for an affair.” Kachka’s vulgar and misogynist suggestion is that Jean Stafford should have suffered in silence. But he doesn’t stop there. Boris Kachka, a man who will never be a poet or a novelist or a journalist of any renown, actually has the temerity to write that “Giroux patiently endured broken deadlines,” as if Stafford’s great difficulty with a mentally unstable and philandering husband was some commonplace household task. It was likely that the pressure to produce in these conditions led Stafford to bolt to Random House, but the doltish Kachka actually writes this sentence: “It’s difficult to tell exactly what drove Jean Stafford away.” One can easily hear Peter Sellers speaking this line in a French accent.

Does Kachka stop embarrassing himself? Not at all. In 1963, A.J. Lebiling, Stafford’s third husband and the man who she experienced the most happiness with, died at the early age of 59. This premature death crushed Stafford and made it difficult for her to write fiction. But don’t tell that to the clueless and insensitive Kachka, who neglects to mention any of this when writing about FSG’s 1967 author compilation:

Giroux used it as a chance to prod another of his flailing depressives, Jean Stafford, to finish her autobiographical novel “A Parliament of Women,” only to receive the reply: “There is no book and I don’t know if there ever will be.” There never was.

A flailing depressive? Is that all she was? Never mind that Stafford would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1970 for her Collected Stories — an FSG book. Kachka does not mention this Pulitzer at all. Nor does this sexist pig point out that Stafford was good friends with Roger’s wife, Dorothea Straus. How many author-publisher relationships did Dorothea salvage? We may never know, because it doesn’t fit into Kachka’s “gentleman’s profession” template.

But Hothouse‘s greatest folie de grandeur is the notion that FSG willfully positioned itself as the most distinguished American publisher under Straus’s watch. Many of the Nobel winners that FSG published in the pre-Galassi days emerged by accident. Indeed, the publisher then and now has stayed alive publishing blockbuster authors like Scott Turow, Thomas Friedman, and Tom Wolfe. But the big tell that Kachka is writing for a lonely audience of one is when he shakily assesses FSG’s stature based on its spine:

The Farrar, Straus logo is so engrained in the consciousness of savvy readers that seeing it on sixty-year-old Noonday compilations provokes cognitive dissonance. To say that FSC simply appropriated the logo is not enough.

Who are these savvy readers? Can they be found in Washington next to the savvy insiders? FSG survived not through loyal readers adhering to the brand, but because it gobbled up profitable publishers. But Kachka is so blind to his invented mythology that he calls Walker Percy “a true Giroux-Robbins team effort,” even though his best-known book, The Moviegoer, was published at Knopf, where editor Henry Robbins merely “had some input into Stanley Kauffmann’s heavy editing of the manuscript.” (Robbins was to flee FSG only a few years later under extremely difficult conditions. Kachka is not especially interested in investigating the high turnover among top editors, but he cannot resist inserting any moment where Straus barks, “You’ll be back,” to an FSG employee fleeing to stabler pastures.)

Perhaps Kachka’s inherent squareness and his lack of adventure, seen with his hilarious suggestion that pot passed around a publishing party was dangerous or his equally pathetic fear of legitimate 1960s actvism (“acts of protest bordering on personal threats”), is to blame for this turgid book. The title is surely no accident, given how large chunks of this book are as dull and as boring as the smooth jazz Bruce Hornsby album of the same name. If Kachka is foolish enough to continue with his floundering career as a book writer, it is almost certain that, like Hornsby, he will celebrate every 4th of July just a little tamer than most of the rest of us do.

* — During the last BookExpo America, I attended a party in which a marvelous woman I hadn’t seen in a while kissed me. Kachka stood next to her and looked at me: his small mouth agog, a pathetic paralysis infesting his slapdash bearing, a hilariously pointless anger in his insignificant eyes. He didn’t even have the balls to introduce himself or call me an asshole to my face. Some years before this, Kachka proved incapable of recognizing a clear case of performance art by telephone voicemail. He really seems to believe that it’s still the 1990s. He’s clearly not going to blossom on the clock. But I’ll be the first to buy him a drink if he does.

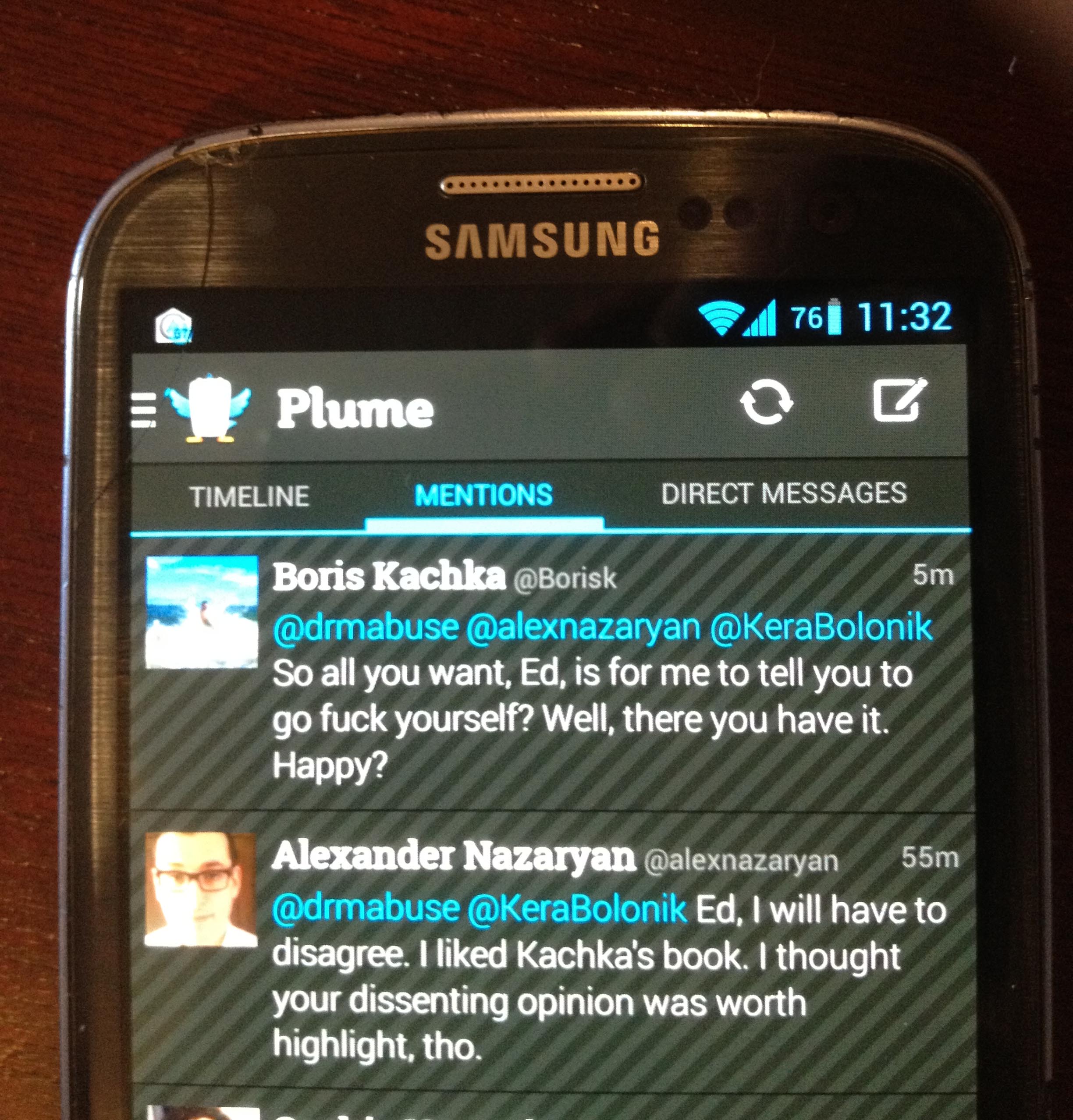

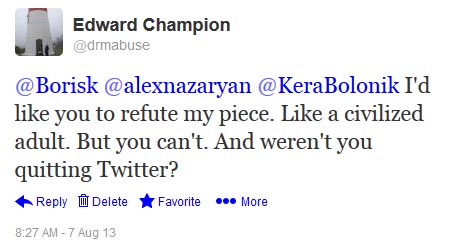

8/7/13 UPDATE: On Wednesday morning, prompted by a Twitter discussion of Boris Kachka’s book involving Alexander Nazaryan and Kera Bolonik, Boris Kachka told me to “go fuck yourself,” as seen in the screenshot below.

Kachka’s tweet was quickly deleted. I responded to Kachka with this reasonable reply:

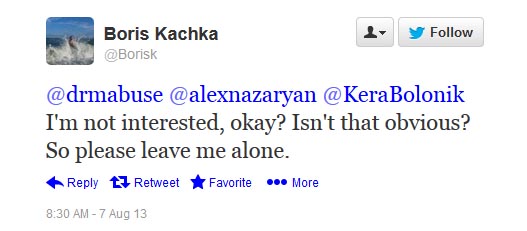

Kachka replied:

So Boris Kachka, unable to refute any of this essay’s charges, prefers to take the low road — a fitting path, given how his book is so obsessed with the vulgar.

Reading Henry Green’s Loving is a bit like going through a valise that a hardcore neat freak has spent many years packing for your once-in-a-decade vacation. You need to extract the chinos for that last summer blowout, but will your unseen friend berate you if you rustle the crisp blue oxford shirt from that fixed and implacable perch just above those promising pants? What Green has given us is a delicate book, difficult to unpack in a thousand words. It is so marvelous that you could spend a lifetime talking about it (certainly many have spent lifetimes teaching it). On the other hand, compared to Finnegans Wake (a Modern Library obligation so massive that I have started reading it early,

Reading Henry Green’s Loving is a bit like going through a valise that a hardcore neat freak has spent many years packing for your once-in-a-decade vacation. You need to extract the chinos for that last summer blowout, but will your unseen friend berate you if you rustle the crisp blue oxford shirt from that fixed and implacable perch just above those promising pants? What Green has given us is a delicate book, difficult to unpack in a thousand words. It is so marvelous that you could spend a lifetime talking about it (certainly many have spent lifetimes teaching it). On the other hand, compared to Finnegans Wake (a Modern Library obligation so massive that I have started reading it early,

The occasion for this revisitation, as explained by a competently groomed gentleman (it was his somewhat eccentrically cut beard that caused me to wonder, and even worry a bit, about his grooming) named Bernard Schwartz (who thankfully did not resemble the man who punched me, although he did ramble on about “Mr. McEwan’s only New York appearance,” which, given my regrettable experience last week with Solar, the latest unreadable turkey squawking from the master’s great hand, seemed akin to boasting of Pauly Shore or Carrot Top headlining a standup comedy night of some long-lasting cultural import), was a 92nd Street Y series styled First Reads. Wood then emerged from behind the stage. (It is probably worth observing that all this was preceded by a prerecorded announcement indicating that cameras and recording devices were “strictly prohibited during the concert.” Given the musical connotations of this noun, I was a bit disappointed that Wood did not sing, play the drums, or play an instrument. He did, however, read DFW’s passages in a somewhat Shakespearean tone, of which he later expressed some doubts. And he was careful to qualify — this, no doubt addressed to the pro-audio book bloc within the audience, who was represented through one question on this subject, to which Wood expressed some polite contrarianism, pointing out, “I do like going at my own speed,” and observing quite rightly the fascistic speed (to be clear, the “fascistic” modifier is mine, not Wood’s; there may be additional modest embellishments throughout this report, which I shall do my best to delineate) prevented one from having a say in the manner — that if one insisted upon a precise aural intonation of the material, one could easily find any number of recorded files read by DFW to hear the appropriate pacing. He would also later note that reading DFW’s sentences aloud was akin to “playing a wind instrument.” And indeed, in light of the many layers of footnotes and commentary and protracted clause-laden sentences, there seems a clear justification to confine DFW’s sentences to one’s own head, and Wood is to be lauded for attempting to dissect the text in a way it was probably not explicitly designed for.)

The occasion for this revisitation, as explained by a competently groomed gentleman (it was his somewhat eccentrically cut beard that caused me to wonder, and even worry a bit, about his grooming) named Bernard Schwartz (who thankfully did not resemble the man who punched me, although he did ramble on about “Mr. McEwan’s only New York appearance,” which, given my regrettable experience last week with Solar, the latest unreadable turkey squawking from the master’s great hand, seemed akin to boasting of Pauly Shore or Carrot Top headlining a standup comedy night of some long-lasting cultural import), was a 92nd Street Y series styled First Reads. Wood then emerged from behind the stage. (It is probably worth observing that all this was preceded by a prerecorded announcement indicating that cameras and recording devices were “strictly prohibited during the concert.” Given the musical connotations of this noun, I was a bit disappointed that Wood did not sing, play the drums, or play an instrument. He did, however, read DFW’s passages in a somewhat Shakespearean tone, of which he later expressed some doubts. And he was careful to qualify — this, no doubt addressed to the pro-audio book bloc within the audience, who was represented through one question on this subject, to which Wood expressed some polite contrarianism, pointing out, “I do like going at my own speed,” and observing quite rightly the fascistic speed (to be clear, the “fascistic” modifier is mine, not Wood’s; there may be additional modest embellishments throughout this report, which I shall do my best to delineate) prevented one from having a say in the manner — that if one insisted upon a precise aural intonation of the material, one could easily find any number of recorded files read by DFW to hear the appropriate pacing. He would also later note that reading DFW’s sentences aloud was akin to “playing a wind instrument.” And indeed, in light of the many layers of footnotes and commentary and protracted clause-laden sentences, there seems a clear justification to confine DFW’s sentences to one’s own head, and Wood is to be lauded for attempting to dissect the text in a way it was probably not explicitly designed for.) This life of the mind is fun stuff, as Powers has suggested to us throughout his work. But Wood is simply too married to the idea of characters as distinct individuals to smile. From How Fiction Works: “Even the characters we think of as ‘solidly realized’ in the conventional realist sense are less solid the longer we look at them.” The problem here is that Wood has failed to look long enough to see what Powers is up to. As Edmond Caldwell suggested

This life of the mind is fun stuff, as Powers has suggested to us throughout his work. But Wood is simply too married to the idea of characters as distinct individuals to smile. From How Fiction Works: “Even the characters we think of as ‘solidly realized’ in the conventional realist sense are less solid the longer we look at them.” The problem here is that Wood has failed to look long enough to see what Powers is up to. As Edmond Caldwell suggested

Wood offered some resistance to blogs, but confined his gripes to comments. “There, I think the rule is sanctioned ignorance,” said Wood. And while he outlined a generalized pattern of how people react to a review that I felt fallacious, the difference between Wood and Mendelsohn is that the former was willing to give the format a chance and try to understand it, while the latter was happy to nuke the site from orbit like an uninformed cretin.

Wood offered some resistance to blogs, but confined his gripes to comments. “There, I think the rule is sanctioned ignorance,” said Wood. And while he outlined a generalized pattern of how people react to a review that I felt fallacious, the difference between Wood and Mendelsohn is that the former was willing to give the format a chance and try to understand it, while the latter was happy to nuke the site from orbit like an uninformed cretin.