Every artist repeats himself, often without being cognizant of it: stylistic tropes, character archetypes, peculiar metaphors, and distinct storytelling moves. The more prolific the artist, the more likely the artist will repeat himself. I think of how Joyce Carol Oates — herself astonishingly voluminous — mentions the soothing comforts of vacuuming in the aftermath of grief in her memoir, A Widow’s Story, while drawing a similar comparison between death and vacuum cleaning in her short story “Cumberland Breakdown” (contained in I Am No One You Know).

So given that repetition is a creative inevitability, how do you avoid it? And when is repetition acceptable? These are vital questions to consider in an age of franchise fatigue, in a time in which an audience is now asked to devote its entire life to consuming endless reboots, remakes, and spinoffs that offer little in the way of originality.

Speaking for myself, the only way that you could get me to watch another bloated three hour Marvel Cinematic Universe movie (Three hours? Come on! You’re not Tarkovsky!) — whereby the now tedious destruction of New York is now an annoyingly guaranteed and yawn-inducing cliche — is if you locked me in a hotel room with a group of sinuous, supple, and wildly inventive lovers. And even then, my attentions would be more fixated on the far more rewarding existential variations of tendering affection and satisfaction to each and every sybarite who drops by for a mutually beneficial afternoon delight rather than the bullshit spectacle of Manhattan once again — for fuck’s sake, not again! — being reduced to rubble.

It is not that I am against genre. (I have always loved genre passionately!) But artists who work in genre tend to be the worst transgressors of the problem I am addressing here. Furthermore, I am strongly opposed to being bored out of my fucking mind. MCU movies bore me. As do the endless iterations of Star Wars rehashes and retreads, which now fills in every goddamned ambiguity that initially captured my imagination with an indefatigable series of cheap narrative disappointments. (Did we really need to see Boba Fett escape from the Sarlacc Pit? No, we didn’t. Boba Fett was a marvelous invention, the perfect side character who said very little and, before Disney+ turned this bloated and ever propagating franchise into a bland carpet rolling endlessly down a Poltergeist-style hallway of limitless length, Boba Fett’s laconic presence invited you to speculate about just why he became a bounty hunter. I’ve been told that Andor actually breaks out of the formula, but I am frankly too fatigued by all the George Lucas wankfests to dive in.) I could not give two fucks about The Walking Dead, even though I enjoyed the flagship show in its early seasons. Characters move from one location to another, kill zombies, fend off some villain of the season (such as Negan or The Governor). Lather, rinse, repeat. Same shit, different day, different television spinoff.

But Fringe? Farscape? Twin Peaks? Issa Rae’s great series Insecure? They ended at just the right time. No problems there! For that matter, Better Call Saul struck a heartbreaking note of artistic perfection while also neatly aligning itself with its cousin, Breaking Bad. Twin masterpieces! Both shows in the Alberquerque universe arguably represent some of the best television of the last twenty years. Because the writers knew when their time was up. They knew the precise point when they were about to repeat themselves. I have great hope for For All Mankind, which possesses enough of an imaginative arsenal to run for multiple seasons without becoming dowdy, largely because of the innovative way in which the show jumps forward a decade each season with its “What if?” premise.

Brian K. Vaughan is one of the best living comic book writers working today. Why? Well, it’s largely because he knew when to wrap up Paper Girls. When Saga hit a heartstopping cliffhanger in Issue #60, Vaughan and artist Fiona Staples took a four year hiatus and didn’t return until last year. And Saga has sustained its high artistic quality because this dynamic duo knew that they couldn’t repeat themselves and that they needed a long break to get it right. But Dave Sim? Jesus Christ, what a tragic fall from grace. The man who changed the possibilities of what independent comic books could be succumbed to distasteful misogynistic incel rants. All because he was so singularly obsessed with hitting Cerebus #300. Imagine a world in which Cerberus stopped at Issue #150. Dave Sim would be a hero rather than a well-deserved pariah.

At 75, Stephen King may be the best example of pop fiction staying power that we have. While there are undeniable King tropes (the dangerous religious zealot, the endearing simple-minded sidekick seen with Wolf in The Talisman and Tom Cullen in The Stand, and an empathy for blue-collar types that has rightly caused his books to be revered by many), the man is still successfully working in other non-horror genres such as crime (Billy Summers) and dark fantasy (Fairy Tale). And while he has been self-effacing about declaring himself the “literary equivalent of a Big Mac and fries,” his capacity to grow as a writer in his seventies and still win us over would suggest very strongly that he’s a lot more than this.

The excellent audio drama Wolf 359 knew when to quit. As did Wooden Overcoats. The Amelia Project? Nicht so viel. It is now a stale and uninventive retread that no amount of new characters or talented actors can salvage.

Trevor Noah knew when to leave The Daily Show. As did Jon Stewart. At least initially. But after taking a few years off to write and direct films, his ego became seduced by the fame, attention, and money that emerges from churning out more of the same. He returned to the airwaves with the same schtick, vastly eclipsed by the far more thoughtful and more hilarious approach of John Oliver on Last Week Tonight. (I truly hope that Oliver knows the precise moment to quit. Because it would be a pity to see him transmute into a disinterested has-been hack.)

The Who and Led Zeppelin both ended at nearly the right time (although the less said about everything after Who Are You, the better; opinions vary on whether or not Zeppelin’s final album, In Through the Out Door, was entirely necessary). Had Keith Moon and John Bonham lived longer, I think it’s likely that they would have turned into 1980s corporate rock sellouts that Gen X punks like me would have justifiably ridiculed with formidable sneers. And while John Lennon’s assassination by Mark David Chapman was truly terrible, imagine (har har!) what kind of hideous reactionary Lennon would have transformed into in the 1980s. Or Kurt Cobain. Or Janis Joplin or Jimi Hendrix. This fun but unsettling speculative game — which I personally guarantee will enliven a dull party — is what Billy Joel (who quit writing songs long after his talent was tapped, but who at least had the decency to spare us further River of Dreams drivel) was referring to when he sang about “the stained-glass curtain you’re hiding behind.”

In other words, every artist has a finite amount of talent and imagination. Sometimes it extends within a given project or a stylistic approach. Sometimes it’s represented in an entire career. I used to love T.C. Boyle’s work, but now I find him insufferably repetitive. Why? Because Boyle hasn’t changed his formula much in the last ten years. It is highly doubtful that we will get another novel on the level of World’s End or The Tortilla Curtain from him. And that’s a damned pity. At some point around 2014, Boyle stopped caring about whether he was evolving as an artist and started to phone it in.

Lost? Battlestar Galactica? Both shows lasted at least one season too long. They were both wildly popular and didn’t seem to understand that the creative well had run dry. Imagine if they had ended at the right time.

The artists who didn’t know when to stop or change things up fell into what I’m calling “the content trap.” The content trap is what happens when something distinct and original becomes wildly successful, but corporate greed or an artist’s narcissistic need for chronic adulation gets in the way of knowing when the jig is up. Ego prevents an artist from knowing when it’s time to end things. And what we usually get are inferior repeats of the same stories that initially captured our imagination. Let’s be honest. If Douglas Adams had actually confined his Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series to the trilogy format, what would be so bad about that? I think Adams knew that So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish was never going to live up to the three books that preceded it. He was so impaired by the need to write content for the fourth book that publisher Sonny Mehta had to move in with Adams to make sure that he finished the novel. Douglas Adams — for all of his wit and radio drama innovation — fell into the content trap. On Community, Dan Harmon had a running joke in which characters suggested that the show had “six seasons and a movie” of material. And had Community been renewed for a seventh season, there is no way that its formidable writers could have summoned anything as brilliant as “Remedial Chaos Theory.” Dan Harmon didn’t fall into the content trap.

John Cleese — a genius whom I worshipped as a teen — hasn’t been funny in years. His best days are far behind him. Why? Because he fell into the content trap. He’s bringing back Fawlty Towers decades later and it’s completely unnecessary. On the other hand, I had thought that Star Trek: Picard was a dead retread incapable of further innovations, but the third season has somehow found new life under showrunner Terry Matalas. Here was a show that fell into the content trap, but that somehow clawed its way back, even resolving an Ensign Ro storyline from decades before. In other words, it’s not impossible for a content trap victim to reverse course and find a vital reason for creating new art. (Witness the surprising endurance of Doctor Who over more than fifty years — although its recent partnership with Disney+ does have me greatly worried — or Philip Roth’s multiple periods of resurgence. Or how about Tina Turner’s Private Dancer (after four dismal solo albums)? I’ve lost track of the number of comebacks that Miley Cyrus has had, but you’d be hard-pressed not to groove to Endless Summer Vacation.)

Most artists find it difficult to escape the content trap once they fall into it. But here’s the good news: everyone loves a comeback. And if we start demanding higher standards of the work we love and that goes on on and ever ever on rather than accepting bullshit like some hopelessly compromised head-bobbing fanboy who settles for, well, anything, then even once beloved artists have a shot at surprising us with the imagination and talent that is buried somewhere within them. That is, if they can successfully resist the large bags of money that corporate overlords continue to wheelbarrow into their palatial estates so long as they continue to offer us more of the same.

(Special thanks to my friend Tom Working, whose insightful comments partially inspired this essay.)

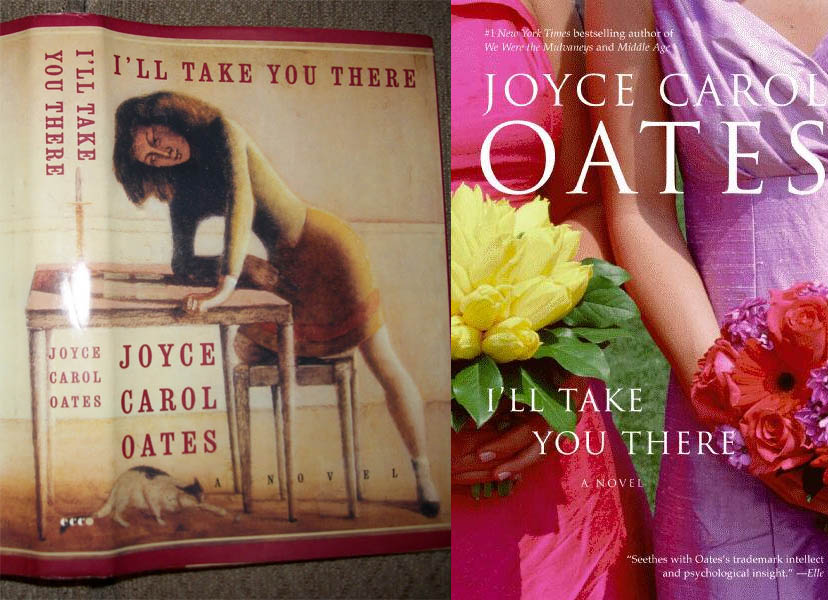

Weiner cited the wildly divergent covers for Joyce Carol Oates’s I’ll Take You There — the Ecco hardcover a striking drawing, the paperback being composed of flowers — as an example of how drastically publishers are willing to alter their covers for women audiences. And she mentioned her own battles with Target, who demanded that the cover for her new book All Fall Down be tinted blue, with the street in Philadelphia considered too gritty for audiences coveting the usual sunny hues.

Weiner cited the wildly divergent covers for Joyce Carol Oates’s I’ll Take You There — the Ecco hardcover a striking drawing, the paperback being composed of flowers — as an example of how drastically publishers are willing to alter their covers for women audiences. And she mentioned her own battles with Target, who demanded that the cover for her new book All Fall Down be tinted blue, with the street in Philadelphia considered too gritty for audiences coveting the usual sunny hues.

Correspondent: In considering the ideas of nightmares as fiction — because, of course, this is The Corn Maiden and Other Nightmares, that’s the title of this book — I think of John Hawkes. I think of Poe. I think of Kafka. I think of Shirley Jackson. The nightmares in The Corn Maiden, I think, differ. Because these tales are careful in the way that they relate psychological realism to the dream state. In the title novella, you juxtapose this troubled mother who is losing her daughter with this sacrificial ritual. There’s the psychological grief in “Helping Hands,” which triggers a nightmare, it could be argued. In “Fossil-Figures,” you describe Eddy Waldman’s work as “covered in dream/nightmare shapes.” So I’m curious how psychological realism gives shape to these nightmares that are in your fiction.

Correspondent: In considering the ideas of nightmares as fiction — because, of course, this is The Corn Maiden and Other Nightmares, that’s the title of this book — I think of John Hawkes. I think of Poe. I think of Kafka. I think of Shirley Jackson. The nightmares in The Corn Maiden, I think, differ. Because these tales are careful in the way that they relate psychological realism to the dream state. In the title novella, you juxtapose this troubled mother who is losing her daughter with this sacrificial ritual. There’s the psychological grief in “Helping Hands,” which triggers a nightmare, it could be argued. In “Fossil-Figures,” you describe Eddy Waldman’s work as “covered in dream/nightmare shapes.” So I’m curious how psychological realism gives shape to these nightmares that are in your fiction.