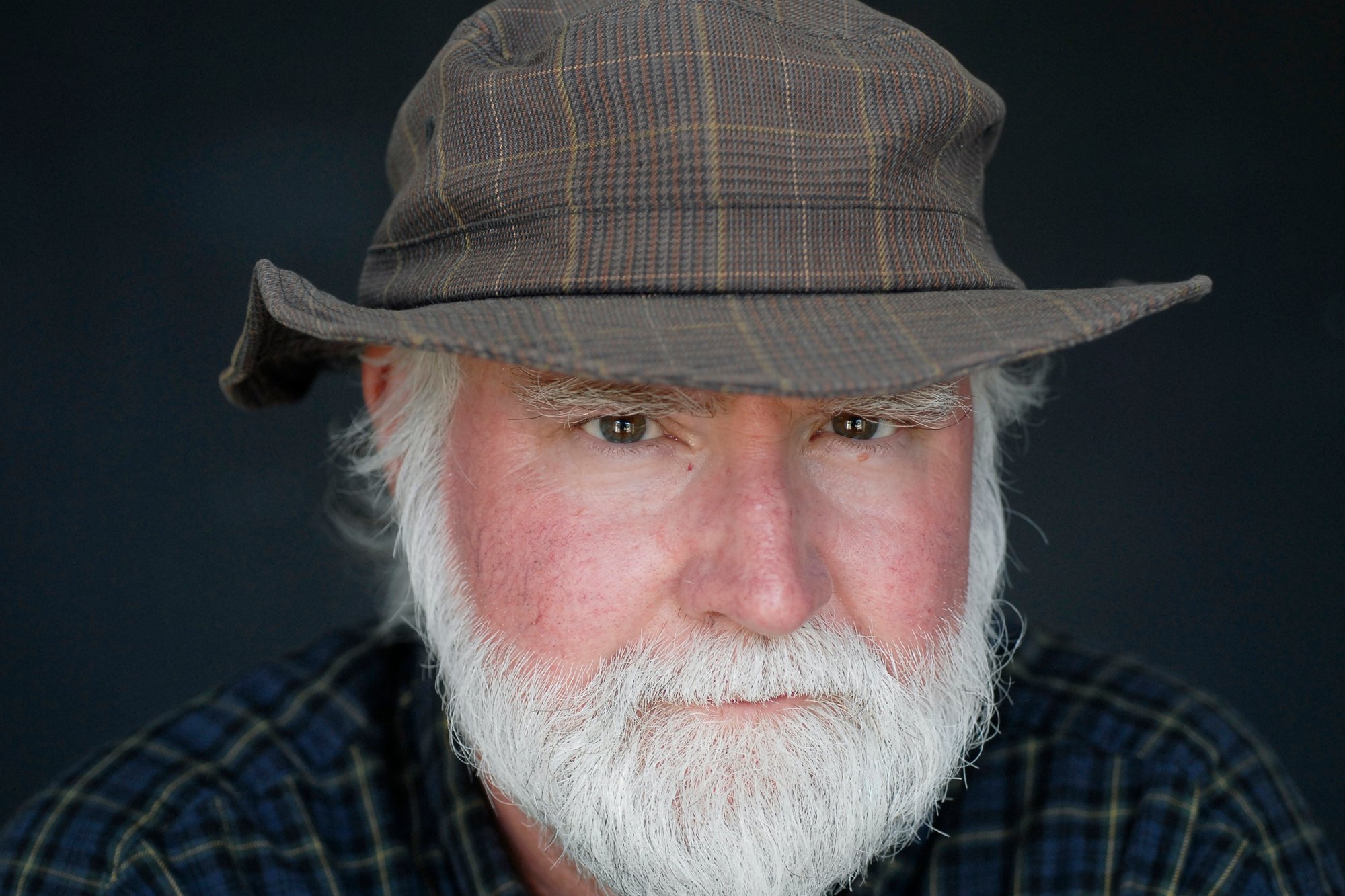

Nicholson Baker is most recently the author of Traveling Sprinkler. He previously appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #200.

Author: Nicholson Baker

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Subjects Discussed: Attempting to talk in the early hours of the morning, the many beginnings offered by poems vs. the many beginnings offered by the Internet, digital enjambment, tobacco dip videos, Paul Chowder’s songwriting, Baker’s protest songs, Method writing, the development of song lyrics over the last few decades, Dance Music Manual, when dance songs go on too long, Lopoerman, loops, buying a shotgun mic from B&H, phones that beep during conversations, being a proponent of the kick drum, the theology of percussion, how fiction and music composition create different principles in drawing from other work, Medea Benjamin, Glenn Greenwald, the importance of sticking it out, Paul Chowder’s politics vs. Jay’s politics in Checkpoint, Edward Snowden, the difficulty of writing controversial books, when world leader surnames become too incantatory, attending political protests, political recoil, a highly attuned relationship to language and its effect upon political commitment, language as overused wooden blocks, songs as a way of taking back familiar words, Obama’s kill list, synesthesia, stretching out a word to melodic effect, Marvin Gaye’s “Sexual Healing,” Tracy Chapman’s “Change,” how repetition causes you to look at a word in a different way, Paul Chowder’s “The Right of the People,” the discomforting sight of protesters who are pepper sprayed, peaceful assembly, singing the Bill of Rights, cultural appropriation, Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” and Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up,” Thicke’s injunction against Gaye’s family, Ray Parker’s “Ghostbusters” and Huey Lewis’s “I Want a New Drug,” the scant chords and melodies available in pop music, the swift creation of “Blurred Lines,” George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord” and the Chiffons’ “He’s So Fine,” Baker’s views on the movie music business, why Hans Zimmer is a hack, Baker’s appreciation for Paul Oakenfold and trance, the bassoon, how Harry Gregson-Williams ripped off John Powell’s score for The Bourne Identity, Carol King, efforts to duplicate songs in the 1970s, “Narrow Ruled,” putting a dot on a margin to note a passage vs. favoriting a tweet, filling notebooks with quotes from other books, analog vs. digital forms of “signing someone else’s mind signature,” anthologists who hunted for Shakespearean gems, Logan Pearsall Smith, the downside of typing too fast, forgetting handwriting, the foreign nature of writing a thank you note in the digital age, the importance of exertion, articles about the end of handwriting, handwriting vs. keyboards, how reading things aloud slows time down, Baker’s recent Harper’s essay arguing against Algebra II, the socioeconomic impact of abolishing Algebra II, Jose Vilson’s response to Baker’s article, knowledge vs. the way teachers express knowledge, Algebra II as a requirement that increases human suffering, turning core subjects into electives, educational budget cuts, compulsory education, negative high school experiences, fallacious approaches to teaching the essay, E.B. White, Robert Benchley, Baker’s attendance at the School Without Walls, the burden of having to know and do things that you don’t like, Dan Kois’s unpardonable anti-intellectualism, the importance of challenging perceptions, the importance of sitting still, migration routes of the Goths through Europe, including more choice into education, living a life where nobody is asking you to do anything, the trancelike state of being bored, House of Holes, Samuel R. Delany’s notion of pornotopia, Katie Roiphe’s advocacy of House of Holes, why so much of literary sex is a downer, House of Holes as realist novel, Grindr, Tinder, small town life, Yellow Submarine, Baker’s appreciation for Schmidt’s soliloquies in The New Girl, Baker’s appearance on The Colbert Report, why penis is an insufficient name, using the deep hindbrain words, “The Penis Song,” Victorian pornography that appears throughout many of Baker’s novels, John Cleland’s Fanny Hill, Librivox and audio books, the presence of radio in the Paul Chowder novels, how audio reveals the inflection of words, the inclusion of more Chowder lead-ins in Traveling Sprinkler, Baker’s secret stash of personally recorded radio bumpers, and talking into field recorders.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: In The Anthologist, the first of these two novels, there’s this moment where Paul Chowder describes how he’s fond of books of poems. Because no matter where he flips around, he can always be at the beginning. And as he says, “Many, many beginnings.” It occurred to me that this is also the perfect description for the Internet, which actually appears quite prolifically and is almost a cultural repository in the second Paul Chowder book, Traveling Sprinkler. You seem to have, in many cases, swapped the names of poets and real people from The New Yorker with people in bookstores, such as the great Miss Liberty at River Run Books.

Baker: Oh yes.

Correspondent: And, of course, I actually found a lot of those tobacco dip videos on YouTube. You were actually quoting directly from them.

Baker: Oh sure! You don’t want to make those up.

Correspondent: (laughs) You don’t want to make those up?

Baker: No, they’re too great as is.

Correspondent: Well, you’ve written a good deal about the Internet in essays. And I have to ask: to what extent do you feel that the Internet has almost replaced or augmented poetry? There’s certainly plenty of digital enjambment out there. So I’m wondering about this.

Baker: (laughs) Digital enjambment. What a great idea! Well, I think what the Internet has done is that it’s enormously enriched our lives. And it does have that feeling of pieces, many of them. Breaks. Fragments. All over the place. And poems also are short and fragmentary and you kind of come across them and have that moment and go away. But I guess the difference is that I use the Internet — I kind of dip in constantly to learn things. Whereas when I’m in a mood to read a poem or when I just happen to read a poem, it slows everything down. And it has kind of the opposite effect on me. It doesn’t make me want to leap off in eighteen directions. It makes me want to just stop and say, “Oh my god! That pulled that thing apart! That held me still.” So it has that opposite effect. So the two are identical. In some ways, they’re in competition with each other. But in some ways, they’re similar.

Correspondent: What’s the future of poetry with these promising distractions? This enjambment of a different sort?

Baker: The future of poetry is independent, I think, of the way that we publish things. And it’s probably more closely linked to the future of pop music than some poets would want to admit. Because they want to have that division. They want to say that song lyrics aren’t poems. But obviously the two are short clumps of words that often rhyme or have some kind of metrical thing happening. And certainly the future of song lyrics is terrific, I think, isn’t it? I mean, have we ever — certainly in the history of my life — has there ever been a time when you are just constantly discovering new songs and old songs and comparing things? These great websites that tell you the history of a certain lyrical idea. I mean, it’s really happening. So I would think that the strength of that thread, or that theme, is going to propel poetry forward. And then there’s also kind of the realization that some of modernism was a mistake. Not all of it, but some of it. It was aggressive in the wrong way and was kind of disturbingly exclusive and rejecting of comprehensibility and all that. So the poets I like have learned from all of those terrific things that happened in the early part of the 20th century, but they want to be read, you know?

Correspondent: Paul Chowder’s songwriting is not a new development. There is, in fact, this song in The Anthologist that goes “I’m in the barn / I’m in the bar-harn / I’m in the barn in the afternoo-hoon.”

Baker: (laughs) Yes.

Correspondent: So why do you think songwriting turned out to be more of a muse than poetry for Paul Chowder this time? Was it from jumping off some of the hip-hop schemes that you were analyzing in The Anthologist? You were, of course, recording these songs and putting them onto YouTube, which many of us were watching with some degree of curiosity. So to some degree, I guess, this is a form of Method writing. I’m wondering how Chowder’s sensibilities as his affinities permutated here.

Baker: Well, I think Chowder is a guy who would love to be a better poet than he is. And he’s looking for a way out. He’s looking for a way out of a kind of situation in which he’s trapped in the level he can reach as a poet. So he’s looking for a way out. But he’s also looking for a way back in. And, I mean, I certainly share this with him. I share 90% of his thoughts. So I can just say that poetry is beautiful and calls to you. And then there’s moments where you just think, “God, I need something different. Something more. I don’t understand it. I don’t understand why so many people do it. All that feeling.” And getting back to music and trying to fit two art forms together is really hard and excitingly challenging. It was for me to imagine him as a lyric writer, not a very good one. But you know, he does his best. Because song lyrics are so different. They have to be simpler. And when you’re writing song lyrics and trying to match them to a melody or invent a melody, the words that come out are different than the words that come out if you’re just sitting with a typewriter. So I think it was just the thrill of the chase. It was the excitement of the idea that this maybe is the key. So if he, and if I, can possibly write some tunes or get some rhythms going that have a certain bouncy danceability or hummability or something? Wow! That is fun! And then manage to get some words going. I mean, it felt to me, once I started to play with music again, like a new chapter in my life. And so when I was writing the book, and I was writing the novel and songs at the same time…

Correspondent: Did you also become an astute scholar of all the various dance genres much like Paul Chowder? Did you go down that rabbit hole as well?

Baker: Yeah! Sure! Of course I bought a textbook called Dance Music Manual.

Correspondent: So it was actually that textbook.

Baker: Oh yeah. I studied it! Very, very thick. A very heavy textbook. And dance music really puzzles me in a way. Still I don’t really fully get it. Because the songs are too long. I love to listen to a loop. And I’ll happily listen to sixteen bars of a loop and then another layer comes in. And 32. At some point, I want the song to be over. And I think that because I grew up with the Beatles, I want it to be over at around two and a half to three minutes. And dance songs, because you’re supposed to dance to them and they are segued with other songs, go on a very long time. And so I really still haven’t learned the form of the dance song. But when I’m writing, I listen to them all the time.

Correspondent: But all of the songs that you did as Nick Baker get into that kind of trance state of a constant loop and a constant series of rhythms where you’re sort of promulgating some kind of concern about politics or something along those lines. Some of them go on quite long as well. So is the loop really the way to identify the dance song? I mean, did you start off with loops? I almost don’t want to direct you to Looperman. Are you familiar with this site? They have all sorts of loops you can use for free that I use for this particular program.

Baker: Really? Well, I don’t ever use loops. I use Logic Pro.

Correspondent: Okay.

Baker: Which is Apple’s music software. Just as my character does in the book. It’s $200. Tons of instruments. Fantastic deal. And it does everything that you need it to do. Although it isn’t Pro Tools, which is the industry standard and all that. Which is $600. And I couldn’t afford that.

Correspondent: Did you actually go down [like Paul Chowder in Traveling Sprinkler] and get a shotgun mic from B&H? (laughs)

Baker: Absolutely.

Correspondent: You did! Okay.

Baker: All that software.

Correspondent: You had that similar problem of “Oh, do I need to lay down a lot of money for this great mic?” Wow!

Baker: No. All my theories about the importance of stereo sound versus mono sound I just dumped into the book. I believe in stereo. I’m a strong believer in stereo. So I bought the mic not from B&H — oh, yes! I bought it, but not from — yeah, I bought it from B&H!

Correspondent: Wow.

Baker: And in fact, I thought of bringing it along. Because it’s kind of soothing when you’re traveling to do some music. And I thought I could practically fit the mic stand. The mic is about three feet long. And it’s pretty durable. So I thought I could put it in the suitcase. And then I thought, “Nah. Something might happen.”

Correspondent: Is it the Rode mic?

Baker: I can’t remember. It’s ATK or something.

[Mysterious beeping sound.]

Baker: I’m sorry. That’s me. I’ll turn this off.

Correspondent: (clutching his dying smartphone, which has less than 5% battery life) No, it’s actually me. Or is it you?

Baker: I think it’s me telling me. It’s telling me that tomorrow I’ll be in Washington DC. (laughs) How helpful!

Correspondent: I’m turning mine off too.

Baker: The DC Book Fest.

Correspondent: My power’s actually about to go out. So there you go. So okay…

Baker: Okay. So let me. Okay. So loops. There are different ways to think about the word “loop.” And most dance songs, and a lot of pop songs these days, are built on the looping principle. But what you don’t want to do is take somebody else’s loop and say, “Ooh! That sounds good. I’ll use it in my song.” Or at least I don’t want to do that. Because you want to build something that is your own. So I usually start with a little piano riff that goes on for four or eight bars. A little something. A chord. Just an interesting chord. Or I start with maybe a hi-hat sound that sounds just a little bit odd and interesting. Or maybe some percussion that has a bit of pitch to it that then makes me think of another sound. Then I layer, using a lot of trial and error and a certain amount of just dumb luck and whatever; incompetence — layers over that. Until I have, say, fifteen layers of sound. And that’s my loop. And the nice thing, when it goes right, is that the loop is in all of its fully official, big time, near-the-end-of-the-song glory. But you might want to take out five tracks from that when you start. And, of course, the kick drum might come in. And suddenly, sixteen bars along or something.

Correspondent: You’re a big proponent of the kick drum.

Baker: Everybody is. You can’t not be a proponent of the kick drum!

Correspondent: (laughs)

Baker: Except that it’s kind of an embarrassing term. You know, “kick drum.”

Correspondent: (laughs)

Baker: It sounds sort of like the da-da-da-dum-dah-dum.

Correspondent: You make it sound like John Philip Souza or something.

Baker: Yeah. It sounds like that. But what it is, it’s a massive kind of a chest-vibrating sound that happens every beat or however you want to vary it. And once you get into this world, the theology of kick drum sounds.

Correspondent: A theology?

Baker: The number, the thousands of tiny variations. And the way you can make a chesty kick drum, but with this element of a pop on the top so that you can still get the sense of something bursting, but also get that subwoofer whomp. All of that. People think about that. You have no idea how seriously people take that. Well, you probably do. You’re into music.

Correspondent: Yes. Well, this is really interesting that in your own particular music, you basically say no to taking another loop. And yet in the fiction, we’ve established that you’re drawing very close from reality and from real world examples. Which might almost be like taking a loop and meshing it with another loop.

Baker: Interesting.

Correspondent: And I’m wondering why music allows one set of principles and fiction offers another one. Or is it really simply the expression of a sentence that offers the distinction between music taking loops and fiction taking from cultural reference and so forth?

Baker: Well, yeah, that’s really an interesting thought. I think that I’m always reluctant to quote anything without quotation marks. So I don’t believe in it. The hip-hop world uses sampling a lot, where you take a number of nice sounds — the riff, maybe the chorus — and do things. And it’s obviously brilliant. And they’ve made such great discoveries and combinations. It’s just not something that I’m ready to do yet. I think it’s because, as a writer, I can’t bear the idea that, even involuntarily, I would without remembering quoting somebody else’s phrase and thinking it was my own. It’s just not something that I ever, ever want to do.

Correspondent: Unless you devise a specific sound that can be offered in lieu of a quotation mark.

Baker: (laughs) Who?

Correspondent: A very special percussive sound that nobody else has, that everybody agrees upon. “Alright! Here’s the time where we take from a 70s Funkadelic song.” (laughs)

Baker: Exactly.

Correspondent: There’s another thing I wanted to ask you about. In Traveling Sprinkler, Paul Chowder name-checks both Medea Benjamin and Glenn Greenwald. There’s an interesting line. And this was written before Edward Snowden. “What good does it do me to read Glenn Greenwald’s excellent blog? He’s right about everything and I’m glad he’s doing it. But it doesn’t seem to have any effect.” Well, au contraire!

Baker: (laughs)

Correspondent: Granted, Paul is talking about this in relation to Roz. But Paul Chowder to me is more of a short-sighted version of your typical Baker hero, who is really taking in the world and seeing it with a kind of wonder. And also, it’s not unlike what he said of podcasters, where he says, “They’ll keep on pumping it out. But then they’ll puff up and die.”

Baker: (laughs)

Correspondent: To which we got into a minor disagreement. But that got cleared up. But I actually wanted to ask you. Why do you think that Paul Chowder does not really appreciate the long-term effect of keeping at it and sticking at it? Because that is just as much a part of the journey of being an observer, of being an intellectual seeker, of being a curious type. And so that is very curious why this is outside his temperament.

Baker: Well, I think you put it beautifully, Ed. You have to be patient. You have to keep saying the things over and over again. But that doesn’t mean we all don’t have moments of despair. Which happened, say, in the ramping up to the first Iraq War. All those brilliant op-ed pieces. All that marching. All that sustained argumentation that made the case that this was a mistake was for naught. It was going to happen. It was scheduled, planned, whatever. The launch date was planned. And it happened. And that filled me with a kind of despair. Because I thought, What is the function of rational argument and public discourse when it’s just not going to work? When there’s that feeling, that wave of almost frenzy or a thirst for war. And I think it’s worth including that sentiment if we’re going to be true to our own political lives, which are mixtures. You go up and down. Sometimes you think, “Well, my god, we’re making progress and good ideas are coming out. And good people like Medea Benjamin are saying incredibly powerful, moving things and brave things.” And then it all seems for naught. And it doesn’t get anything accomplished. So you then feel that despair. So I just had Chowder follow the ups and downs of that. But I’ve hinted that towards the end. You know, there’s a moment where his friend Tim gets arrested. And he says, “I’m glad Tim is writing the book.” And the point is that Paul Chowder is too caught up in his own worry, his own love complexities, and the mixed-upness of his own life to do something sustained like write a book against drones. But he’s very glad someone else is doing it. And at some point, he thinks that maybe he can actually do something. In my case, I’m trying to, in a sneaky way, do the same thing. I’m trying to say, “I’m going to present you with a human life.” And this is a person that, if it works, you’re going to recognize this guy. You’re going to see some things about people in this person that you think, “Oh, that’s familiar.” And you’re going to see him struggle and have dissatisfaction and give you some little political ideas to think about. So by the end of the book, I’m not going to have tired you out or disgusted you with overpoliticizing, I hope. Although maybe I redlined there. But I’m going to have included that component in a fictional life. So that the aim of the book was political in a sense. It was to try to write some sort of anti-intervention book, but to do it singingly. To sing the pain a bit and include all the other distractions that a normal life has.

Correspondent: But there are two interesting points here. Because both Glenn Greenwald and Medea Benjamin this year — I mean, when Medea Benjamin basically shouted out to Obama in a way that nobody else would, suddenly, at that moment, she was taken seriously after all these years of ridicule. Same goes with Greenwald. You centered on the two figures who stuck it out and actually became a vital part, I think, of the political discourse. Simultaneously, I’m also thinking of Chowder’s vacillating political position and comparing it to Jay from Checkpoint, where he wants to assassinate Bush for the good of humankind. And that also is a kind of intervention as well. And I’m curious why every political argument that you approach in your fiction tends to involve an intervention of some kind. It’s either an intervention that comes from within or an intervention that comes from without. I mean, is this really just kind of what you see as the American impulse right now? I mean, we’re clearly not in the streets complaining about drones or complaining about the surveillance state and all that. But it is something that this conviction does face intervention in all of your fiction, I think.

Baker: Well, first, I totally admire and — I mean, who wouldn’t admire what Glenn Greenwald did with Snowden? Which was all before. But I love his blog. I admire it so much. I’m terribly jealous of his ability to stick with it and to be patient and to go after and to say similar things, but bring new facts into it. And Medea Benjamin — I mean, I just can’t stand it. She’s so brave. And I love that.

Correspondent: You’re envious of the bravery?

Baker: Well, you know, I have been to marches a little bit. And I published a political book. Human Smoke was a very controversial book. And it’s really hard. It really hurts sometimes. The criticism, the sneering, the unfairness. The kind of misrepresentation of what you’re trying to do in order to make you into a figure of ridicule. In order to make whatever you have to say not have any weight. You know, it does hurt. And it’s hard. And I can only do it once in a while. And even when I’m doing it, I’m doing it about the Second World War! I’ll write a few letters and sign some petitions and I’ll march. I mean, I was up in Portland at an anti-Syrian intervention. Candlelight vigil. Lighting candles. But I’m going to retreat to another time and try to make the argument a different way. I’m trying to undermine the militarist impulse by undermining some of the justifications for the Second World War. I’m trying to do it indirectly. But it’s also an escape. I mean, it’s so hard to talk about the present in a fresh way. That’s the hard part. The names. The names are so familiar. And I don’t want to hear the name “Obama.” I don’t want to hear the name “Assad.” I’m tired of the names. And yet obviously those are the names you have to use. And so, you know, it feels like you need to figure out another way.

(Loops for this program provided by ShortBusMusic, ferryterry, danke, and Progressbeats5.)

The Bat Segundo Show #520: Nicholson Baker (Download MP3)