(This is the twenty-fifth entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: Finnegans Wake.)

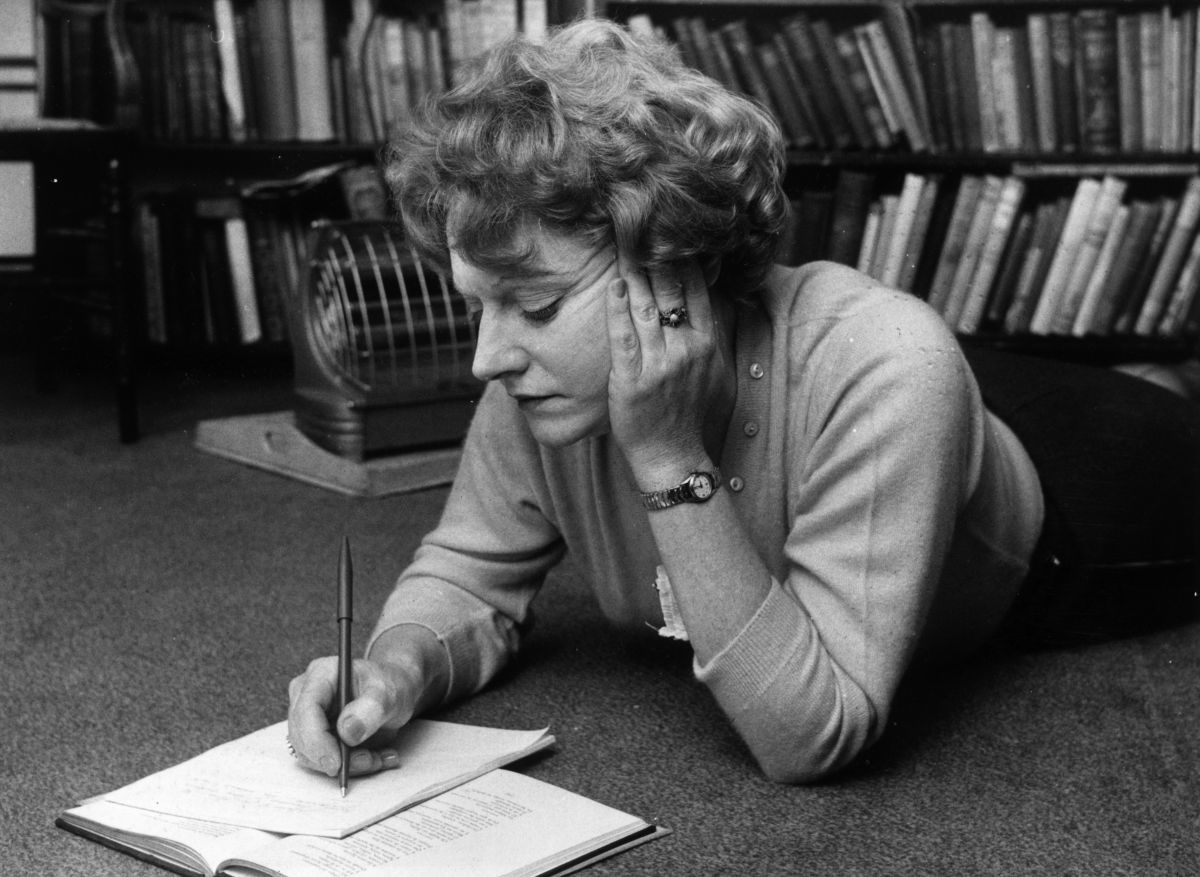

We are two days away from the great Muriel Spark’s 100th birthday. Yet, despite New Directions’s valiant reissue of her remarkable work only a few years ago (along with a quiet event planned on Thursday at the 92nd Street Y, which stands incommensurately like a shaking child in the vast shadow of Edinburgh’s impressive celebratory blowout), we are no closer to literary people universally singing her praises on this side of the Atlantic than we are in stopping men from wearing black socks to bed. And that’s a shame. Because Muriel Spark was truly one of the most innovative writers of the 20th century. She was a bold and an economical stylist who packed far more attentive detail and character speculation into one paragraph than most contemporary writers wrangle into a chapter, and she did so with high style, grace, and ferocious wit. The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, her most enduring and popular novel (and, through a magical twist of fate, the next volume in the Modern Library Reading Challenge), certainly sees Spark’s great gifts on full display, but it is also a book that demands constant and even obsessive study.

We are two days away from the great Muriel Spark’s 100th birthday. Yet, despite New Directions’s valiant reissue of her remarkable work only a few years ago (along with a quiet event planned on Thursday at the 92nd Street Y, which stands incommensurately like a shaking child in the vast shadow of Edinburgh’s impressive celebratory blowout), we are no closer to literary people universally singing her praises on this side of the Atlantic than we are in stopping men from wearing black socks to bed. And that’s a shame. Because Muriel Spark was truly one of the most innovative writers of the 20th century. She was a bold and an economical stylist who packed far more attentive detail and character speculation into one paragraph than most contemporary writers wrangle into a chapter, and she did so with high style, grace, and ferocious wit. The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, her most enduring and popular novel (and, through a magical twist of fate, the next volume in the Modern Library Reading Challenge), certainly sees Spark’s great gifts on full display, but it is also a book that demands constant and even obsessive study.

I have read Brodie four times within the last two years. It is very possible I will read it four more times within the next two. I am inclined to press this richly entertaining book, no more than a hundred pages, into the hands of anyone who purports to take literature seriously, but who has somehow ignored Spark to hold up some bland offering from one of those “Most Anticipated” lists published at The Millions that nobody will remember or quote from in a decade.

Brodie is both a portrait of an exuberant teacher determined to educate a carefully selected group of girls so that they may be better equipped when “in their prime” and an incredible tableau of 1930s Edinburgh, such as the “wind-swept hockey fields which lay like the graves of the martyrs exposed to the weather in an outer suburb.” Miss Brodie may or may not be a tyrant. (She is fond of Mussolini and Italian culture.) One can read the book anew and come away with an entirely different opinion of the title character. The novel tantalizes us with flash-forwards (which can also be found in many of Spark’s later novels, such as The Driver’s Seat and Territorial Rights, which are also well worth your time) revealing the fates of the schoolgirls in adult life, leaving us with impressions of how formative life and education influences unknowingly in later years. One reads little snippets of the six girls under Miss Brodie’s tutelage from the present and the future– Rose “pulling threads from the girdle of her gym tunic” in class or Jenny not experiencing any sexual awe “until suddenly one day when she was nearly forty, an actress of moderate reputation married to a theatrical manager” — and asks how much Miss Brodie is responsible for corrupting fate, with Spark slyly implicating us as we become more curious.

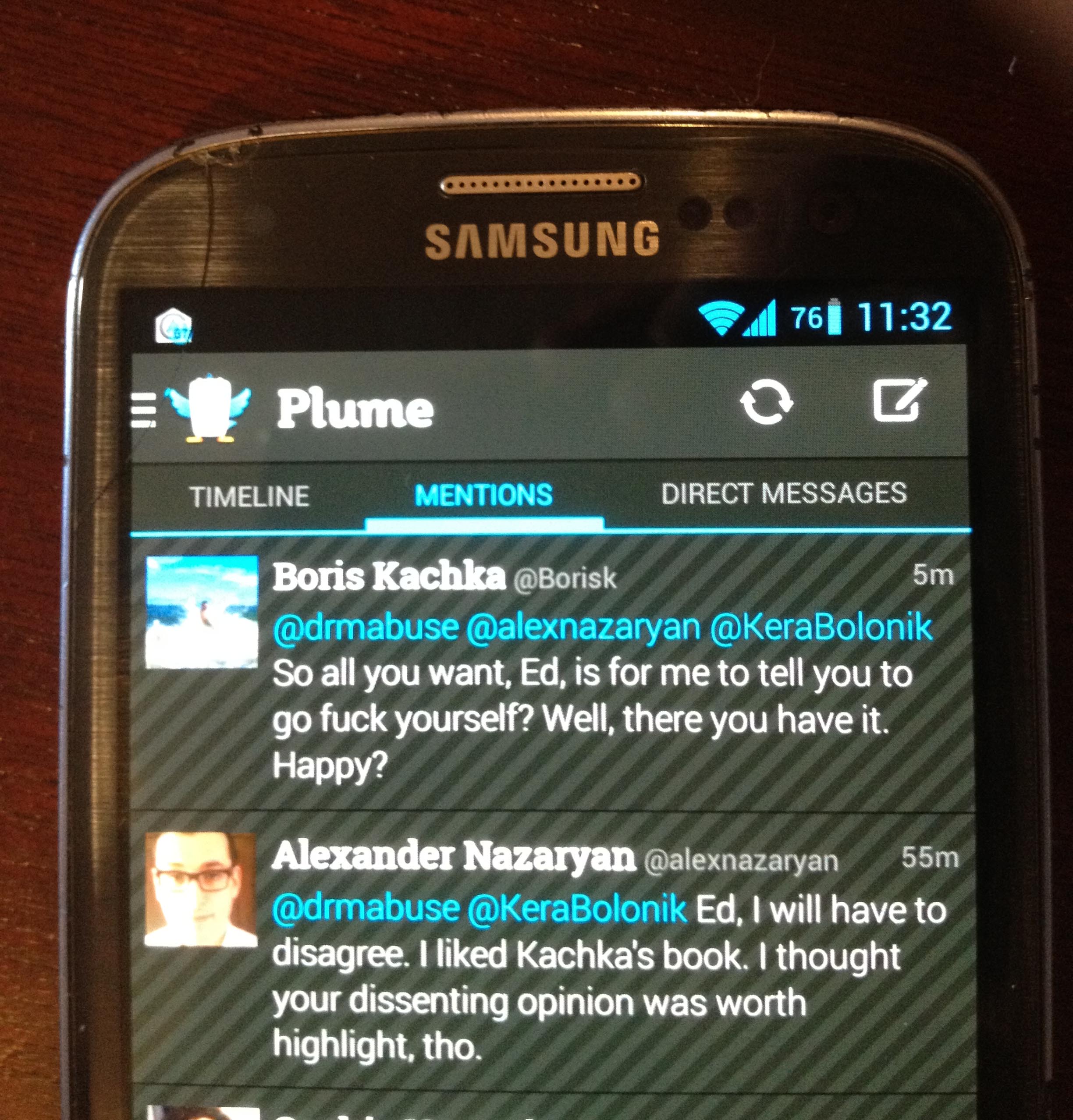

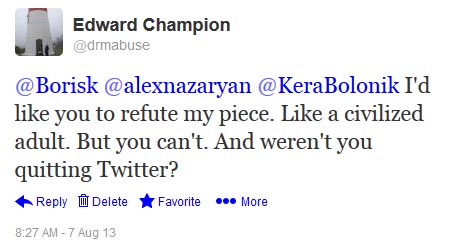

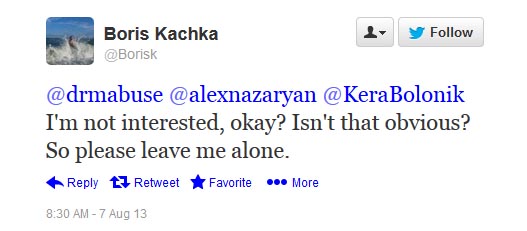

Muriel Spark wrote this masterpiece in less than a month. This is especially amazing because, much like the magnetic properties contained within the glowing amber necklace Miss Brodie wears when off-screen romance inspires a new step in her exacting stride, this short novel reads as if an exquisite jeweler had painstakingly ensured that not a single element could ever fall out of alignment. And Spark sculpts many glistening carats along the way: the fictitious letters that two girls write after imagining Miss Spark’s love life, the creepy, one-armed artist Teddy Lloyd who also teaches at the school and disguises his true pedophilc nature through the sham panacea of Catholicism and family life, and the lingering question of which schoolgirl betrays Miss Brodie and causes her to lose her job. The novel presents us with many hints and details that hide in plain sight, but that all contribute to an atmosphere in which the girls end up coming up with explanations (often fictitious and sometimes apostate) for what is both seen and not seen. Miss Brodie’s careful lessons, which include a field trip into a rougher part of Edingburgh and often involve knowing the roots of words to better understand them, are perhaps being applied in dangerous ways. And in an age where people judge people who they haven’t met based on what they think they know from a social media profile, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie remains potent and necessary reading.

Spark’s lecture “The Desegregation of Art,” delivered before a crowd of New York literati on May 26, 1970, offers useful insights into the ambitious gauntlet she felt obliged to throw down as an artist and gives us a sense of what is very much at stake in Brodie. She firmly believed that literature existed to infiltrate and fertilize the mind and denounced any fiction that stood in the way of this lofty artistic goal. If that meant tossing out socially conscious art that was not “achieving its end or illuminating our lives any more,” then this was the price to pay for better art that reflected the depths and thorny hurdles of life. She insisted that “ridicule is the only honourable weapon we have left” and believed that addressing wrongs emerged not so much from instant outrage, but through “a more deliberate cunning, a more derisive undermining of what is wrong. I would like to see less emotion and more intelligence in these efforts to impress our minds and hearts.” Much as Spark detested being a victim in her life, she believed that art reveling in victimhood turned readers into oppressors.

So we are left with Brodie as a remarkable volume that fertilizes our minds even as it challenges our own interpretations. Spark’s honorable ridicule in Brodie may very well lie with the way she shrewdly sends up how people are perceived for their failings based on superficial shorthand. And this extends even to the hypnotic allure of Miss Brodie’s own teaching. At one point, Miss Brodie observes that “John Stuart Mill used to rise at dawn to learn Greek at the age of five” and that the teacher herself learned from this lesson. Mill is a particularly funny choice, given that this philosopher was known for utilitarianism and that we are seemingly experiencing a short “utilitarian” novel when we read Brodie. But, of course, we aren’t. For one wants to reread it yet again.

The intrepid literary adventurer plunging forward on a bold bender for real-life inspiration is often viewed with contempt by any practitioner transforming bits of his life into analeptic artistic truth withstanding the test of time. The adventurer shakily balances the author’s complete works like vertiginous trays stacked tall enough to scrape plaster flakes off the ceiling as the letters and the collected marginalia and the autobiographical tidbits are swirled into a overflowing flute by a jittery finger serving as a makeshift cocktail straw. If not written off as a slightly smarter TMZ reporter who has somehow retained the ability to read despite being barraged daily by Harvey Levin’s soul-destroying smile, such an apparent gossipmonger, even if she is cogent enough to know that fictional characters rarely spring from a singular source, is still tarnished as that rakish yenta who reads fiction for the wrong reasons.

As I have ventured further into this years-long Modern Library project, I’ve come around to the daring idea that, for certain sui generis authors (and Muriel Spark is certainly one of them), one may indeed find deeper appreciation in the way they forge art from the people surrounding them. It isn’t so much the schema of who matches up with whom that should concern us, but rather the fascinating way in which characters defy an easily identifiable origin, turning into a form of fictionalized life that feels just as real on the page as any spellbinding life experience. There is a fundamental difference between the novelist who runs out of raw biographical material mid-career, her limited inventive faculties and inherent disconnection with humanity dishearteningly revealed with mediocre and unconvincing and blandly repetitive offerings in late career (see, for example, the wildly overrated Joyce Carol Oates, surely one of the great living literary embarrassments in the early 21st century), and the novelist who seizes the reins of an indefatigable spirit that runs quite giddily to the very end.

For someone like Muriel Spark, who was fiercely protective of her privacy and her public image, this is not necessarily a slam-dunk proposition even when many of the real life details match up. The formidable literary biographer Martin Stannard secured Spark’s reluctant blessing to get his hands dirty on details occluded in Spark’s remarkably opaque autobiography, Curriculum Vitae. Stannard, like many before him, pegged Christina Kay, the schoolteacher who taught Spark at the age of twelve, as the predominant inspiration for “the real Miss Jean Brodie.” Both Kay and Brodie insisted that their girls were the “crème de la crème.” Miss Kay also took Spark and her fellow students on great cultural adventures into Edinburgh. Both were keen on Italy and shared a rather clueless interest in Mussolini. (As late as 1979, Spark would insist that Miss Brodie was not a fascist and that Brodie’s admiration for Il Duce had more to do with Benito’s powerful masculinity, as it was perceived in 1930, which leads one to ponder the 53 percent of white women voted for Trump in 2016. Some weaknesses in human perception regrettably endure, despite the best history lessons.)

But much as the great Iris Murdoch regularly transcended reality to achieve jaw-droppingly marvelous art, which she defined as that which “invigorates without consoling,” one finds a similarly spellbinding spirit within Spark’s equally incredible novels. Once you read The Girls of Slender Means, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Memento Mori, The Driver’s Seat, or A Far Cry from Kensington, if you have even the faintest desire of wanting to know how art works, you may find yourself obsessing over just how she was able to put so much into her novels. Ian Rankin, writer of the rightfully well-regarded Rebus novels, found himself precisely in this very position, reading The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie over and over again over the course of thirty years and always finding new details, even wondering if the titular character was the hero or the villain. (Some of Rankin’s work on Spark when he was pursuing a Ph.D is available online behind a paywall.)

And if you read Brodie, you may very well join us on this pleasantly fanatical quest. We are told at the end, with one of the characters hiding from the truth of how her life has been altered, “There was a Miss Jean Brodie in her prime.” And that seemingly innocent notion, in Spark’s nimble hands, is the white whale that turns any reader into Ahab.

Next Up: Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop!