[4/20/21 UPDATE: Comments left on this post led to two thorough and detailed investigations which uncovered severe allegations of grooming, rape, manipulation, sexual assault, and much else from Blake Bailey. I conducted an investigation focused on Bailey’s time as a teacher and the allegations of grooming and manipulation. The New Orleans Advocate‘s Ramon Antonio Vargas focused on what happened to Bailey’s former students as adults. I urge you to read both of these stories. (Mr. Vargas is a great reporter. And the two of us communicated with each other to ensure we had accurate information.)]

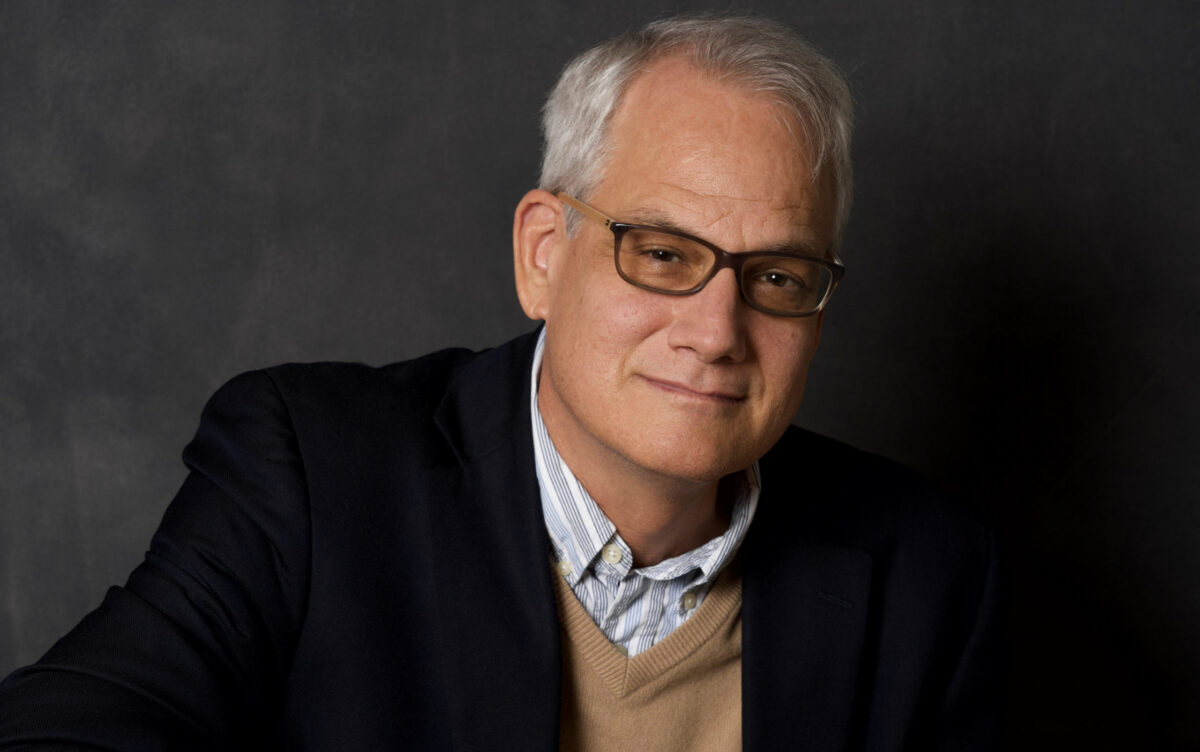

When I first met Blake Bailey at the back of a Le Pain Quotidien outlet just south of Central Park in the spring of 2009, he was carrying a large foamcore blowup of a glowing New York Times review of his most recent book. He pointed to this gargantuan slab, raising it above his head like a dubious trophy, and spent at least five minutes pointing to it and laughing hysterically as I was setting up the mics, vacuuming up the rapturous sentences in a way that made me (and the person who I was with) think, “Christ, how much ego-stroking does any man need?” While I had come to expect occasional insecurity from authors during my long former tenure as a literary interviewer (which I did my best to assuage with off-air empathy before I rolled tape), this was one of the most absurd displays of narcissism I had ever seen, obscenely disproportionate to the delicate hand that had forged two remarkable literary biographies with lapidary care. But when I interviewed Bailey, he did eventually win me over with his charm — the same “charm” that has allowed him to exhume all sorts of sordid skeletons from the unlikeliest subjects; he even got me to summon a few vulnerable truths that I wish I hadn’t spilled when I met him years later on the Charles Jackson bio. This is pretty much the promotional manner that this boiler room man of letters has used to win over the entire literary world with his current volume, a Philip Roth biography with the decidedly uninventive title of Philip Roth. Like most literary biographers (and, for that matter, most literary interviewers), Bailey is a louche leech and an attention whore with an oleaginous sheen, a dishonest huckster who has built up a career with, yes, some laudable volumes, but ultimately with the relentless Energizer Bunny cadences of a sycophantic solipsist. Fortunately, for Bailey, this is the kind of shameless promotional spectacle that the literary world, which I am mercifully no longer a part of, eats up with the voracity of starved wolves moving in on a recently slaughtered lamb thrown to them by some sadistic god.

Of course, as a Philip Roth fan, I was quite elated when I heard the news that Blake Bailey — the accomplished biographer of Richard Yates, John Cheever, and Charles Jackson — was the big choice enlisted to tackle one of the 20th century most controversial writers. In his previous volumes, Bailey had balanced fairness with gentle tugs at the ugly truths to present literary titans as glaringly flawed, needlessly neglected, and ultimately very human. What made Bailey a compelling biographer was the way in which he aligned himself with the underdog. His empathy (at least on the page) not only applied to his troubled subjects, but to the many patient friends, lovers, and literary associates who endured volatile excesses and often booze-fueled torrents of abuse. In A Tragic Honesty, Bailey wrote of the way in which Richard Yates’s patient agent, Monica McCall, did her best to make Yates a better writer while contending with Yates’s often shaky life circumstances and shaky sense of self-worth. Bailey was gentle in reporting the often fragile dynamic between John and Mary Cheever, implicating both husband and wife through methodical interviews and archival excavation that were impressively vigorous. Bailey spent years combing the dusty stacks and often tracked any connection who was still alive to get a hot tip. If he wasn’t quite Richard Ellmann (who could be?), it was certainly the stuff of solid shoe-leather journalism.

But with his Philip Roth biography, Bailey’s approach has changed to what The New Republic‘s Laura Marsh has perspicaciously described as “an adoring wingman who thinks his friend can do better” — particularly in relation to Roth’s first wife, the troubled Margaret Martinson. Until Martinson enters the picture, Bailey’s biography is the usual even-keeled mix of life-forming incidents and wild jaunts through disruptive gossamer. Unfortunately, with this book, Bailey cannot walk the tightrope. For one thing, Bailey is no longer documenting a neglected author on the margins, but a literary giant whose work will very likely stand the test of time. Roth’s stature has very obviously altered the winning Bailey formula for the worse. Roth isn’t a dark horse to root for. He is, instead, an admittedly fascinating egomaniac boasting about how he’s the equal of Malamud and Bellow well before Goodbye, Columbus is even published. (Never mind the seventeen years of duds and shaky curiosities that Roth turned out after Portnoy, including such horrors as The Breast, before stumbling upon Zuckerman and truly securing his genius, beginning with a breathtaking run that began with The Counterlife.) What’s so disappointing (and indeed outright nasty) is the way that Bailey has traded in his compassion for casual misogyny and a complete lack of fairness in relation to Maggie Martinson. Much as it pains me to say, Bailey’s Roth assignment turns out to be his Faustian bargain. Bailey now operates with a repulsive misogyny that is incongruous and completely unacceptable in an age of #metoo and women significantly victimized by COVID job losses.

You know that something is awry when Maggie’s first introduction comes saddled with a footnote in which Bailey has “changed the names of Maggie’s first husband and their daughter.” Did Bailey burn his sources? Was this an edict from Norton legal to prevent a lawsuit? Is Bailey about to launch some character assassination to perform ardent fellatio to his hero? Yes, definitely, on the latter question. You read some passages of this biography wondering if Bailey was writing sentences on his knees with Vaseline-smeared lips extended to their widest diameter for Roth’s throbbing member. (To cite one of many embarrassing examples, Bailey approaches Roth’s calculated courting of Andrew Wylie and his eventual bolt from FSG for lucre as if Roth is somehow a humble naif or a victim. He willingly buys into Roth’s bullshit that he “begged” FSG’s Roger Straus to make him a sizable counteroffer, which not only demonstrates just how much of a sad and naive mark Bailey is in matters of ruthless business transactions, but the pathetic amounts of dun that Bailey is eager to apply to his covetous nose in order to more exquisitely adulate his subject.)

As I read on and became increasingly unsettled by the nasty sexism directed towards Maggie (of which more anon), I wondered why Bailey only seemed to draw solely from Maggie’s journal (how did Bailey obtain this?) as opposed to including any independent sources outside the Philip Roth Seal of Approval, which would seem to me to be the responsible journalistic approach. I was stunned to find this endnote:

PR gave me MR’s journal and the abortive beginnings to her novel(s) in progress contained therein. The story of how this intriguing artifact came into PR’s possession is told at the end of Chapter 19.

One then flips to the end of Chapter 19, only to find this footnote from Bailey:

In most cases I’ve tried to cull only the most telling, pertinent, and perceptive passages in Maggie’s journal, and hence may have inadvertently misrepresented the basic tenor of what is, indeed, a pretty insipid piece of writing.

In short, Bailey has imbibed the Roth Kool-Aid and is far from objective. If anything, this development — complete with the needlessly subjective aside that Martinson was only capable of “insipid writing” (this was a journal, for fuck’s sake) — completely erodes any trust we can have in Bailey as a fair-minded biographer.

Instead of considering Maggie’s trauma of growing up with an alcoholic father who was arrested, Bailey instead offers a nonchalant aside about how this personal anecdote was possibly shoehorned into And When She Was Good. Instead of empathizing with possible sexual abuse from her father, Bailey skims over this. He describes her as possessing “a gimlet eye” at the age of eighteen, establishing Maggie as a masterful manipulator of men. There isn’t a shred of sympathy for Maggie becoming pregnant while studying at the University of Chicago. Bailey also cheapens Maggie’s aspirations to be “a scholar and a bohemian” by painting her as merely “an unwed mother in college.” We have only Roth’s July 19, 2012 email to Bailey used to uphold the spurious claim that Maggie believed she was impregnated “by force.” Pages into Maggie’s first appearance in the book, Bailey has aligned himself with Roth and villainized Maggie and used dubious sources to uphold this convenient narrative.

Bailey skims over abuse that Maggie’s first husband inflicted upon her, but casts needless doubt on these ugly assaults by claiming that it doesn’t “appear to be entirely untrue.” And this comes even though both of Maggie’s children remember growing up in a household of violence. Then Bailey has the audacity to besmirch Maggie further by slyly suggesting that her affair with an auto mechanic named Bob may have suggested that Maggie deserved it. It’s a setup that foreshadows the abhorrent misogyny to come. “Look at this evil bitch who slept around,” Bailey seems to be saying. “Is it any wonder why our man Roth was victimized?”

In short, Bailey is not on the side of women. And certainly not on the side of “difficult” women. But then anyone steeped in Bailey knows that this old Southern white boy grew up in an environment of casual misogyny. As Bailey wrote of his brother Scott in his memoir The Splendid Things We Planned, without much in the way of familial rebuke:

I think he called her a cunt at some point (the word was such a normal part of Scott’s vocabulary that it didn’t really convey the usual nastiness).

Maggie is then portrayed as someone with “likable spunk.” When Roth’s friend Herb Haber says that he was impressed by Maggie’s qualities (“very bright, very funny, good sense of humor”), Bailey negates this observation one sentence later by claiming this to be a persona. Then Bailey proceeds to describe Maggie’s “withered and discolored” vagina by way of Roth’s transposition in My Life as a Man. After glossing like a mercenary pornographer on physical attributes and Roth’s lack of physical attraction to Maggie, Bailey then describes Maggie’s Chicago railroad flat not much in terms of how she actually lived, but more in relation on how Maggie’s boarder slept around. He can only countenance Maggie’s friend Jane Kome as “a big blonde who was ‘attractive in a kind of blowzy Blythe Danner way'” (the quote is Roth’s). And then Maggie gets pregnant from Roth and there is some perfunctory mention of the “heavy bleeding” she suffers (little concern, of course, to the anguish that a woman undergoes after an abortion) and inserts a quote from Roth only sentences later, “I had my first sense that she was crazy.”

So Maggie is established by Bailey (serving as Roth’s willing sock puppet) as some wild, insane, and adulterous free spirit who was set to ruin the Great Man of LettersTM rather than a woman of her own mind and soul. He describes Roth as being “unsettled by the novelty of her rage” after Maggie’s abortion, as if having to contend with the feelings of a woman who has made a significantly stressful decision should be received not with empathy, but as a troubling inconvenience. He never once considers Maggie’s pain or the behavior that Roth may have committed to induce such fury. Throughout all this, Roth carries on affairs, at least the ones that Bailey is privy to. Could it be that a woman might be justifiably angry towards her lover if, in the immediate aftermath of her abortion, her lover has affairs behind her back and shows disdain? At no point does our good old Southern biographer even consider this. He is too seduced by the Roth legend. And if he has to surrender his empathy, well, then that’s the cost of doing business.

He describes Maggie “weepily harangu[ing]” Roth after Roth selfishly spoiled her two weeks of vacation. Note the use of “harangue” — which is lecturing someone in an aggressive and critical manner. Maggie is an “aggressive” woman, not a thinking and feeling soul. “Harangue” is the kind of clinical word you use when you want to dismiss someone’s feelings. The fact that Bailey has modified this with “weepily” suggests that any tears that Maggie rightfully spilled for being betrayed are largely superfluous.

More Bailey misogyny: Maggie is described as having “a brittle laugh.” Maggie is “relentless” in showing “her displeasure” when Roth abruptly leaves Chicago. She “acquits” herself by playing hostess (as if Maggie is incapable of being pleasant or social in any way). Maggie acts “like a pig.” And when Maggie joyfully waits for Roth as his ship comes in, Bailey describes her as “waving radiantly in a white dress that made her look like a summer bride.” The implication is clear. Maggie is a woman trying to manipulate Roth into marriage. Bailey interviews a man named Gene Lichtenstein, whose wife reports that Maggie screamed (while house-sitting in a Bowery apartment by W.H. Auden), “I don’t want a strange man coming here overnight! How dare he!” (Bailey italicizes this quote to stack the deck against Maggie. But we don’t have any information about why Maggie would say something like this. Aside from the reality of roommate dynamics, particularly temporary roommate dynamics, when you live in a crowded apartment, things can get tense. Without context, one gets the sense that Bailey is grasping at straws to further declare Maggie as evil incarnate.)

Bailey is such a smug and self-serving elitist that he also has no compassion for the desperate lengths that people will go to when they are completely impoverished. When Maggie is broke and has to pawn Roth’s old Royal typewriter in order to survive, Maggie is portrayed as the one who betrayed Roth, rather than a victim of dire hard-scrabble reality. Maggie announces that she is pregnant. And it isn’t too long before Bailey lines up a quote declaring Maggie to be “an hysterical schizophrenic Gentile girl.” And this is the way it runs until the tragic end.

I could quote Elaine Showalter or Kate Zambreno or any number of smart feminist writers to tell you why all this is completely and distastefully wrong. But surely these examples — taken with the examples that Laura Marsh has tendered — abundantly demonstrate that Blake Bailey is a misogynist. Bailey offers scant redeeming qualities about Maggie. She lives only as a vessel for which Roth to deposit his entitlement. And Maggie isn’t the only victim. In his Roth bio, Bailey can only view women as histrionic and enraging and kvetching — even if they happen to be single mothers who are struggling.

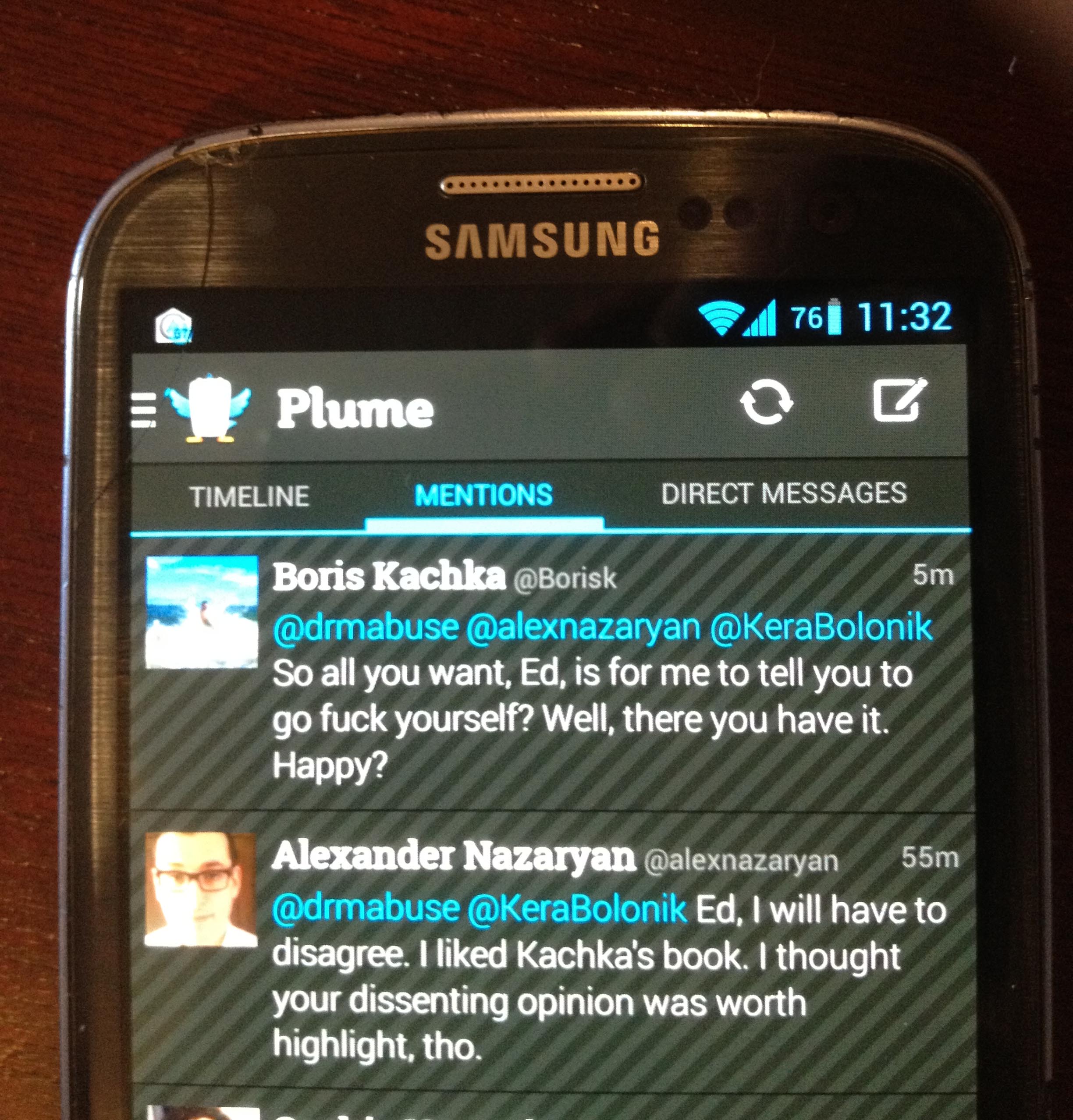

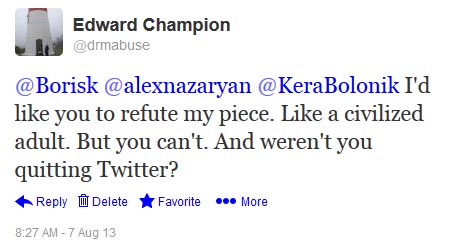

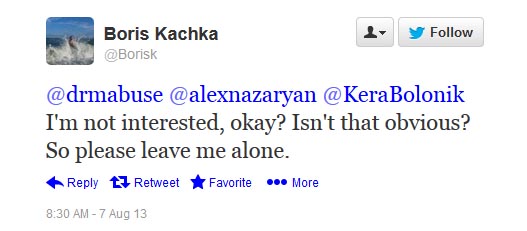

If you call out Bailey on his misogyny, it turns out that he is a spineless thin-skinned coward and not much of a man about it. I truly wanted to understand why a biographer who had written empathy-driven volumes in the past would stoop to such a stunning low. I offered a fair-minded question to him on Twitter. Bailey replied, claiming that I was “disparaging” him. He claimed that he had talked with Maggie’s family and then he blocked me. His reply was favorited by a bountiful variety of fellow misogynists who were happy to cosign onto his sentiments — which included the author Jonathan Carroll, biographer Lance Richardson, cultural journalist Costanza R.d’O, and the proprietor of Neglected Books. Bailey appears incapable of recognizing the vile hatred he has towards women. I mean, I haven’t even ventured into how he portrayed Claire Bloom. I will leave others to sort that out. But he clearly has an ugly strain of misogyny that he needs to reckon with. Unfortunately, this also aligns with the Philip Roth legend. You look the other way when a brilliant writer is being sexist and dismissive and abusive. You ignore the facts. You ignore the way that glossy hagiographers like Bailey cover up the sordid details. You simply print the legend and sell as many copies as you can.

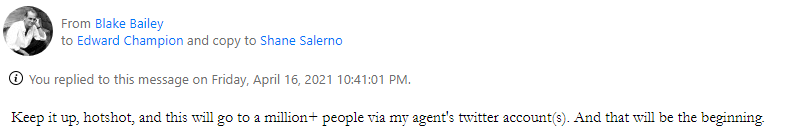

4/16/21 11:00 PM UPDATE: Shortly after this review went up, Blake Bailey threatened that he would ruin me, with a cc to his agent. Screenshot below:

4/18/21 3:00 PM UPDATE: I have received a number of messages and comments alleging that Bailey committed unspeakable behavior to eighth-graders while teaching in New Orleans in the mid-to-late 1990s. If you were a student of Bailey’s during that time, please email me at edATedrants.com. Anonymity and sensitivity guaranteed. Thank you. (Concerning the comments left publicly here, Bailey contacted me, claiming, “It is untrue that I EVER committed an illegal sexual act.”)

4/19/21 4:15 PM UPDATE: The Story Factory, which represented Blake Bailey as an agent, sent me the following email:

Please be advised: Immediately after we learned of the disturbing allegations made against Blake Bailey, The Story Factory terminated its agency representation with Mr. Bailey on Sunday, April 18, 2021.