This is the second of two Moneyball reviews we’ve published. The first, featuring two fictitious sportscasters, can be read here.

I came to Moneyball not having read Michael Lewis’s book. There wasn’t really a good reason. Because I do read source material for a film whenever possible. Why? Because I like to play comparison games in my head. And because if the film doesn’t match up to the book, then I can figure out why. Or if it does measure up (and then some), I can analyze the differences.

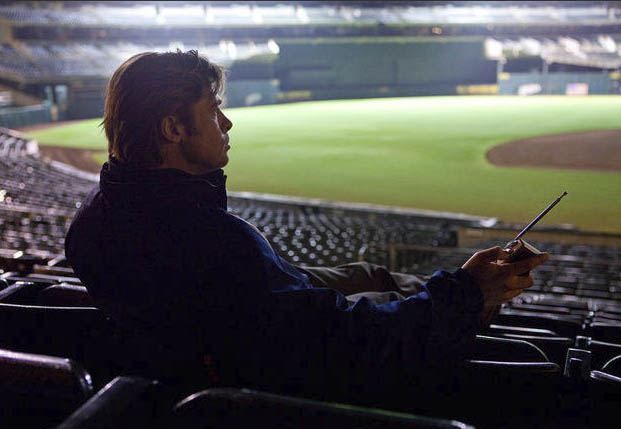

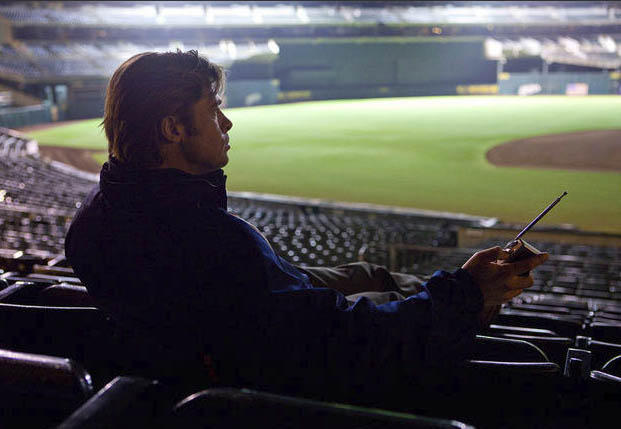

Oddly, I didn’t do so when I saw The Social Network, which Moneyball is clearly trying to ape: from the Sorkin dialogue that managed to survive a zillion rewrites and doctoring to the shots of 21st century retro computing (2001 in Moneyball, 2004ish in TSN) to the meetings where old people need to be convinced of something new and foreign (in TSN‘s case, when the fictional Zuckerberg is being deposed by lawyers or telling the Harvard people why he doesn’t give a fuck about them but does about Facebook; in Moneyball, when beatific Brad Pitt as Billy Beane drops his masks and tells a room full of Fathers Know Best scouts they don’t know what they are doing.) Maybe Moneyball needed full-blown Sorkin, but I don’t think his script could have saved the movie, which was pretty much unsaveable from the get-go.

Here’s why: it opens with footage (real? doctored? who cares?) of the Oakland Athletics’s 2001 wild card playoffs, a strike against my childhood self who cried out for her 1994 Expos, their bound-for-playoff run aborted by the strike that killed the game and ushered in three rounds of post-season. There’s Jason Giambi before we knew he took steroids. There’s Roger Clemens before we knew he took steroids, perjured himself, and generally revealed himself to be a colossal douchebag of the highest order. And I’m distracted, thinking of the Mitchell Report, Itamar Moses’s amazing play about the late 1980s A’s, Canseco introducing McGwire to the magical elixir of what these drugs can do. And oh yeah, the A’s lose, Schott won’t give Beane any money, and everybody’s fucked until the Fat Kid Math Whiz comes along to save the day and make Beane look good with his Sabermetric-based statistical analysis of underappreciated players.

Moneyball did pick up. I admit, when the movie turned to the streak, the grinding gears caused me to get caught up in the manufactured excitement. I mean, truth sometimes does trump fiction, and Hatteberg’s homer really was something else. But we’re only a couple of clicks away from finding out that Jonah Hill’s character is pure fiction (the truth, in the form of Paul DePodesta, Beane’s real-life assistant GM, got edited out because it wasn’t convenient, so DePodesta refused to have his name included), Beane was only following in predecessor Sandy Alderson’s footsteps, and going the quant route only works for the scrappers if the big guns haven’t figured it out. Also, I was kind of hoping for a cameo by some Theo Epstein stand-in, aka the man who ended up with Beane’s promised GM job at the Boston Red Sox. In fact, why hasn’t Ben Mezrich written about him yet?

Anyway, Beane is still with Oakland, though possibly not for long, as this New York Times Magazine piece reveals. He still hasn’t won a playoff. And that’s great, but is this a movie? It’s not that the lack of a Hollywood ending galls. Because it doesn’t. It’s that the lack of a Hollywood ending reinforces the fact that there wasn’t much of a Hollywood beginning or a middle. In other words, I want my damn 1994 Expos. Now there’s a team that might have changed the game further, and their shot wasn’t just ruined then, it was taken away forever.