PHILLIP: So Senator Sanders, I do want to be clear here. You’re saying that you never told Senator Warren that a woman could not win the election?

SANDERS: That is correct.

PHILLIP: Senator Warren, what did you think when Senator Sanders told you a woman could not win the election?

I must confess that CNN’s Abby Phillip’s “moderation” in last night’s Democratic presidential debate angered me so much that it took me many hours to get to sleep. It was a betrayal of fairness, a veritable gaslighting, a war on nuance, a willful vitiation of honor, a surrender of critical thinking, and a capitulation of giving anyone the benefit of the doubt. It was the assumptive guilt mentality driving outrage on social media ignobly transposed to the field of journalism. It fed into one of the most toxic and reprehensible cancers of contemporary discourse: that “truth” is only what you decide to believe rather than carefully considering the multiple truths that many people tell you. It enabled Senator Warren to riposte with one of her most powerful statements of the night: “So can a woman beat Donald Trump? Look at the men on this stage. Collectively, they have lost ten elections. The only people on this stage who have won every single election that they have been in are the women. Amy and me.”

Any sensible person, of course, wants to see women thrive in political office. And, on a superficial level, Warren’s response certainly resonates as an entertaining smackdown. But when you start considering the questionable premise of political success being equated to constant victory, the underlying logic behind Warren’s rejoinder falls apart and becomes more aligned with Donald Trump’s shamefully simplistic winning-oriented rhetoric. It discounts the human truth that sometimes people have to lose big in order to excel at greatness. If you had told anyone in 1992 that Jerry Brown — then running against Bill Clinton to land the Democratic presidential nomination — would return years later to the California governorship, overhaul the Golden State’s budget so that it would shift to billions in surplus, and become one of the most respected governors in recent memory, nobody would have believed you. Is Abraham Lincoln someone who we cannot trust anymore because he had run unsuccessfully for the Illinois House of Representatives — not once, but twice — and had to stumble through any number of personal and political setbacks before he was inaugurated as President in 1861?

Presidential politics is far too complicated for any serious thinker to swaddle herself in platitudes. Yet anti-intellectual allcaps absolutism — as practiced by alleged “journalists” like Summer Brennan last night — is the kind of catnip that is no different from the deranged glee that inspires wild-eyed religious zealots to stone naysayers. There is no longer a line in the sand between a legitimate inquiry and blinkered monomania. And the undeniable tenor last night — one initiated by Phillip and accepted without question by Warren — was one of ignoble simplification.

Whether you like Bernie or not, the fact remains that Phillip’s interlocutory move was moral bankruptcy and journalistic corruption at the highest level. It was as willfully rigged and as preposterously personal as the moment during the October 13, 1988 presidential debate when Bernard Shaw — another CNN reporter — asked of Michael Dukakis, “Governor, if Kitty Dukakis were raped and murdered, would you favor an irrevocable death penalty for the killer?”

But where Shaw allowed Dukakis to answer (and allowed Dukakis to hang himself by his own answer), Phillip was arguably more outrageous in the way in which she preempted Sanders’s answer. Phillip asked Bernie a question. He answered it. And then she turned to Warren without skipping a beat and pretended as if Sanders had not answered it, directly contradicting his truth. Warren — who claims to be a longtime “friend” of Sanders — could have, at that point, said that she had already said what she needed to say, as she did when she issued her statement only days before. She could have seized the moment to be truly presidential, as she has been in the past. But she opted to side with the gaslighting, leading numerous people on Twitter to flood her replies with snake emoji. As I write this, #neverwarren is the top trending topic on Twitter.

The Warren supporter will likely respond to this criticism by saying, with rightful justification, that women have contended with gaslighting for centuries. Isn’t it about time for men to get a taste of their own medicine? Fair enough. But you don’t achieve gender parity by appropriating and weaponizing the repugnant moves of men who deny women their truth. If you’re slaying dragons, you can’t turn into the very monsters you’re trying to combat. The whole point of social justice is to get everyone to do better.

After the debate, when Bernie offered his hand to Warren, she refused to shake it — despite the fact that she had shaken the hands of all the other candidates (including the insufferable Pete Buttigieg). And while wags and pundits were speculating on what the two candidates talked about during this ferocious exchange, the underlying takeaway here was the disrespect that Warren evinced to her alleged “friend” and fellow candidate. While it’s easy to point to the handshake fiasco as a gossipy moment to crack jokes about — and, let’s face the facts, what political junkie or armchair psychologist wouldn’t be fascinated by the body language and the mystery? — what Warren’s gesture tells us is that disrespect is now firmly aligned with denying truth. It isn’t enough to gaslight someone’s story anymore. One now has to strip that person of his dignity.

Any pragmatic person understands that presidential politics is a fierce and cutthroat business and that politicians will do anything they need to do in order to win. One only has to reread Richard Ben Cramer’s What It Takes or Robert A. Caro’s Lyndon B. Johnson volumes to comprehend the inescapable realpolitik. But to see the putatively objective system of debate so broken and to see a candidate like Warren basking in a cheap victory is truly something that causes me despair. Because I liked Warren. Really, I did. I donated to her. I attended her Brooklyn rally and reported on it. I didn’t, however, unquestionably support her. Much as I don’t unquestionably support Bernie. One can be incredibly passionate about a political candidate without surrendering the vital need for critical thinking. That’s an essential part of being an honorable member of a representative democracy.

Bias was, of course, implicit last night in such questions as “How much will Medicare for All cost?” One rarely sees such concern for financial logistics tendered to, say, the estimated $686 billion that the United States will be spending on war and defense in 2020 alone. Nevertheless, what Abby Phillip did last night was shift tendentiousness to a new and obscene level that had previously been unthinkable. When someone offers an answer to your question, you don’t outright deny it. You push the conversation along. You use the moment to get both parties to address their respective accounts rather than showing partiality.

This is undeniably the most important presidential election in our lifetime. That it has come to vulgar gaslighting rather than substantive conversation is a disheartening harbinger of the new lows to come.

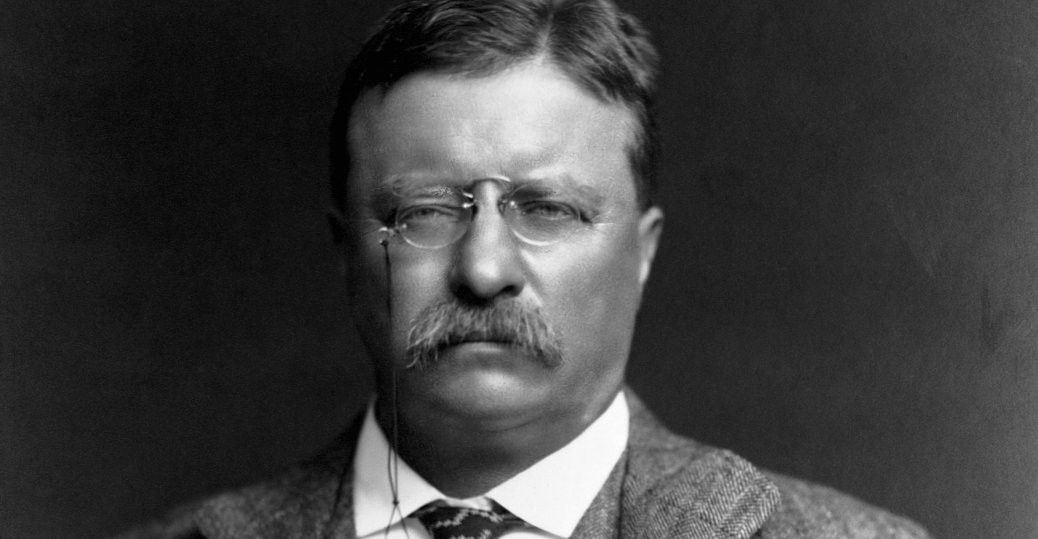

One of many blistering tangerines contained within Mark Twain’s juicy three volume Autobiography involves his observations on Theodore Roosevelt: “We have never had a President before who was destitute of self-respect and of respect for his high office; we have had no President before who was not a gentleman; we have had no President before who was intended for a butcher, a dive-keeper or a bully, and missed his mission of compulsion of circumstances over which he had no control.”

One of many blistering tangerines contained within Mark Twain’s juicy three volume Autobiography involves his observations on Theodore Roosevelt: “We have never had a President before who was destitute of self-respect and of respect for his high office; we have had no President before who was not a gentleman; we have had no President before who was intended for a butcher, a dive-keeper or a bully, and missed his mission of compulsion of circumstances over which he had no control.”