(This is the eleventh entry in the The Modern Library Reading Challenge, an ambitious project to read the entire Modern Library from #100 to #1. Previous entry: Tobacco Road)

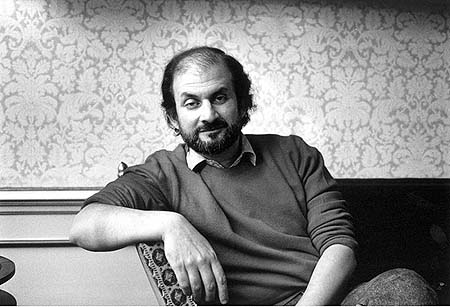

It is somehow appropriate to announce, on the 235th anniversary of my nation announcing its independence from Great Britain, my independence from Salman Rushdie. Midnight’s Children is Rushdie’s allegorical novel about India declaring its independence from Great Britain. My announcement is buttressed by the fact that Rushdie himself is British and presently living in the city I happen to live in, albeit in a less interesting borough than mine.

It is somehow appropriate to announce, on the 235th anniversary of my nation announcing its independence from Great Britain, my independence from Salman Rushdie. Midnight’s Children is Rushdie’s allegorical novel about India declaring its independence from Great Britain. My announcement is buttressed by the fact that Rushdie himself is British and presently living in the city I happen to live in, albeit in a less interesting borough than mine.

Ultimately, one must separate the art from the artist. Patricia Highsmith preferred the company of animals to people, and was cruel to many. Norman Mailer stabbed his wife. Knut Hamsun sent Goebbels his Nobel Prize as a gift and called Hitler “a prophet of the gospel of justice for all nations” after his death. Yet in Rushdie’s case, it has been difficult to draw the distinction, in large part because Rushdie himself is (a) a study in contradictions and (b) not yet dead. The man has sometimes proved so humorless that, when Insulted by Authors‘s Bill Ryan approached him for an insult, the good-natured literary enthusiast received this response from Sir Salman: “Well, why would you want to bring more insults on yourself?” And this seemed a needless extension of Rushdie’s efforts to enforce his will upon others. A few years ago, Rushdie caused Terry Eagleton to partially recant for taking him to task for his neoliberal imperialism. There have been lawsuits. On the other hand, Rushdie did support online criticism much earlier than one would expect from an apparent windbag.

* * *

When I was 22, I read Midnight’s Children for the first time. I was seduced, like many young and impressionable readers, by the language. I also liked Shame and Haroun and the Sea of Stories. I thought The Satanic Verses to be a sensationalistic exercise. The infamous book had earned Rushdie a fatwā, resulting in many years of hiding (with a £10 million tab to UK taxpayers for protecting him over a decade) and a bizarre exchange of letters between Rushdie, John le Carré, and Christopher Hitchens over free speech. Then I read The Moor’s Last Sigh and was greatly underwhelmed. I had the sense that Rushdie’s big mammoth books were less about engaging the reader’s interest and more about forcing the reader to submit. Where was the Rushdie who had charmed in the earlier books?

Still, I decided to give the man another chance. I read Shalimar the Clown and discovered a remarkably ho-hum book despite the promising title. I had observed Rushdie at a few literary events I had attended, seeing a man who appeared to be in love with himself. Since Rushdie wasn’t going away anytime soon, I figured the best thing to do would be to ignore the guy. Let the man stay busy with his half-assed involvement with politics and the film world. Let him have fun persuading supermodels and actresses decades his junior to hop into bed with him. It’s a free country. I didn’t need Rushdie.

So I had thought myself done with the man. It had not occurred to me that Rushdie would pop up like some zombie surprise when I threw down the gauntlet back in January.

* * *

Ultimately one must separate the art from the artist. And I cannot deny, in my thirties, that Midnight’s Children is a stylistically accomplished novel. If you know nothing about Rushdie and you are young and in need of patois, it will almost certainly fulfill a need. It is adept in stringing the reader along. Chapters begin with bold bursts of storytelling: “To tell the truth, I lied about Shiva’s death” and “No! — but I must.” So in Saleem Sinai, you have an unreliable narrator who is lying and twisting and inventing and rambling, but always giving you more. And by bringing in such side characters as the Brass Monkey begging, “Come on, Saleem; nobody’s listening, what did you do? Tell tell tell!” and in deftly deploying dependable tricks such as swapped babies and secret basements and political intrigue and creepy soldiers at tables and convenient coincidences, Rushdie’s gargantuan story reminds the reader that not only is this a story, but it’s a story familiar with story. There are indeed very few places in the book where I wasn’t aware that what I was reading was a story.

But Rushdie is not a writer who I enjoy reading now.

Perhaps it is because life is more than story. Or maybe I have reached a point where story is no longer enough to satisfy me in a novel. I confess that I had to take three twelve mile walks, dutifully flipping and sweating into the pages in the humidity, in order to finish this book. And even then, this eccentric form of self-discipline was countered by the many dogs, kids, and people who I talked with along the way — all of whom proved more worthy of my time and more interesting than Midnight’s Children.

The issue is not India’s marvelous history. Before rereading Midnight’s Children, I decided to read an enormous book (Ramachandra Guha’s India After Gandhi), which outlined the great nation’s vivid history in remarkably clear and quite interesting detail. I figured that knowing more about Nehru and Indira and Sanjay — to say nothing of the Kashmir conflict, the battles with China over Tibet, and the wars with Pakistan — would give me additional insight and interest into Rushdie’s carpet bag. And yes indeed! I became very excited to step right up and enter Rushdie’s rollercoaster.

Until I realized the lack of tensility in the track.

The issue is not my mixed feelings about magical realism. I should probably confess that, while I’m almost always game for fantasy and speculative fiction and Murakami’s surreality, magical realism has felt like a cheat to me. Yet in revisiting the Midnight’s Children Conference, Saleem Sinai’s nose, and his ability to clamber inside other people’s heads, I found these portrayals justifiable because Rushdie remained fairly fluid with his allegory.

The issue is not complexity. Even now, when I read Joyce or Faulkner or Gaddis, I still have a good time doing so. I delight over the sentences and the jokes and the obscure words and the convoluted plots and the complex character relationships revealing more human insight, and I still feel very much alive on the second or third or fourth read. (Since some of these titles are contained on the Modern Library list, I look forward to experiencing this life again!)

Rather, the issue is Saleem/Salman’s desperate need to be liked, to smother the reader into a participatory role rather than that of a peer or a fellow adventurer seeking mystery and ambiguity. Back in 1981, Rushdie’s hey presto smashing mingling mixing form of writing was fresh and innovative: a defiant assertion from a wily wordsmith sticking up for his needlessly neglected home turf.

But thirty years later?

* * *

Statement Posited in Recent Weeks to Random Smart Literary People in Empirical Attempt to Determine Rushdie’s Current Stature: “I’m reading Midnight’s Children.”

Literary Person #1: “Oh, that’s great.” (Begrudging tone, recalling something distasteful — as if one is supposed to like the book rather than genuinely like it. Efforts to press Literary Person #1 on subject prove fruitless.)

Literary Person #2: “I read that in my early 20s.” (It’s the opening paragraph she likes, although she agrees with me that Lolita‘s opening is better. Have you reread it?) “No.” (Would you?) “No.”

Literary Person #3: “Oh….Rushdie.” (Do you like him?) “…” (Do you know him?) “…” (What’s wrong with Rushdie?) “Let’s just say I’d rather read Naipaul.” (You and me both.)

* * *

Indagating further:

independent: adj. 1. not influenced or controlled by others in matters of opinion, conduct, etc; thinking or acting for oneself: an independent thinker 2. not subject to another’s authority or jurisdiction; autonomous; free: an independent businessman.

What type of person initially read Midnight’s Children? Let’s slide the lectern to our man Rushdie:

“The people who like the book most are young. That’s obviously a simplification, but it’s interesting that very large numbers of the people who came to meet me or hear my talks were very young. They were all Saleem’s generation or younger. And I like that. I felt that it was right that the people who were the essential subjects in the book had taken it for themselves and made it their own. Endless numbers of people, not just in Bombay, would come up to me and say, ‘You shouldn’t have written this book. We know all this stuff. We could have written this book.’ And I thought that was an extraordinary thing for a writer to be told — much the biggest compliment anyone has ever paid me. The older generation, I suspect, were often shocked by it.” — Rushdie in conversation with Una Chaudhuri (interview conducted 1983, published in 1990 in Turnstile 2.1)

* * *

In 2011, I am neither especially old nor especially young. I was born in the state of California…once upon a time. No, that won’t do. There’s no getting away from the book.

I was not especially shocked by Midnight’s Children: not even with the book’s admirable depiction of forced sterilizations. But the assault upon the magicians ghetto near the end felt very much like an author desperately needing to justify his novel’s importance:

…standing in the chaos of the slum clearance programme, I was shown once again that the ruling dynasty of India had learned how to replicate itself; but then there was no time to think, the numberless labia-lips and lanky-beauties were seizing magicians and old beggars, people were being dragged towards the vans, and now a rumor spread through the colony of magicians: “they are doing nasbandi — sterilization is being performed!”

Note the way that Saleem telegraphs this horror to the reader without subtlety. Instead of letting the dreadful action speak for itself, Rushdie feels the need to frame it through “the ruling dynasty of India.” The prose here begs (pardon the crass pun) for a rhythmic juxtaposition between “labia-lips and lanky-beauties” and “magicians and old beggars,” but aside from the visual dashes and a few alliterative Ls in the first phrase, we have commonplace discordance. Is this an occupational hazard of communicating through a mishmash Mother India tongue? Saleem is capable enough to joke of a “djinn-soaked evening,” but why the explicit explanation for nasbandi? (Later Rushdie novels are, in fact, less literal than Midnight’s Children. But it is interesting to me that the Rushdie novel that is most celebrated is the one most cemented in explanation.)

* * *

Indagating further:

Rushdie’s early copywriting teaches him to condense. “Midnight’s Children may be long, but I don’t think it’s overwritten.” (The Sunday Times, October 25, 1981)

Rushdie establishes his vocational conditions on his own terms. “There are quite a lot of writers too who do advertising part-time. They both use it for the same reasons, a means to an end. I used to work never more than two days a week in advertising. Those two days would finance the other five. It’s very difficult for a completely unknown writer with no private means to find five-sevenths of his week entirely free for his own writing. In that sense, it was very useful. But it was also good to get out of it.” (Debonair Reviews, February 1982)

* * *

In Midnight’s Children, Saleem declares “…in autobiography, as in all literature, what actually happened is less important than what the author can manage to persuade his audience to believe.” Rushdie has denied that Midnight’s Children is a historical novel in numerous interviews. Is belief the only quality that remains? Aadam Aziz, Saleem’s grandfather, is separated from his friends by “this belief of theirs that he was somehow the invention of their ancestors.” And yet belief related to birth is both problematic and ugly, as when Saleem states his “belief that Pavarti-the-witch became pregnant in order to invalidate my only defense against marrying her.” Then there is India’s “national longing for form” — “perhaps simply an expression of our deep belief that forms lie hidden within reality.” The midnight children do eventually lose belief in the very mechanism Saleem creates for them.

So if belief in Midnight’s Children cannot be tied to history, cannot be tied to people both real and imagined, and cannot be manifested even in the positive events that Saleem describes in hindsight (even the ones that result in betrayal), why then should we believe in Saleem? Why should we believe in Rushdie?

It seems to me that what I have been protesting through this essay — admittedly in the manner of an easily distracted tap dancer who longs for another ballroom — is not so much the idea of a novel reframing intricate history in a quirky and robust manner (which Midnight’s Children does quite well at times), but the troubling notion of Saleem (and by extension Salman) refusing to believe or burrow into belief.

In a 1996 interview, The Critical Quarterly‘s Colin McCabe asked Rushdie about the idea of creating a version of Islamic culture that could be inherited without belief. Rushdie replied (in part), “I felt that I had inherited the culture without the belief, and that the stories belonged to me as well. And because they belonged to me they were mine to use, in, if you like, my way.”

So if Rushdie sees culture, both religious and secular, as mere mechanical strata to pluck and claim as his own, then perhaps I’m objecting to his inherent insensitivity: his brazen ownership of other people’s ideas without recognizable deference to the originators. But in claiming ideas so totally in Midnight’s Children (an admittedly admirable performance), I don’t think he leaves nearly enough for the reader.

Next Up: Henry Green’s Loving!

Correspondent: I’d like to calibrate this conversation with recent events in India. There was, of course, the whole Salman Rushdie affair at the Jaipur Literature Festival. He gets a report indicating that

Correspondent: I’d like to calibrate this conversation with recent events in India. There was, of course, the whole Salman Rushdie affair at the Jaipur Literature Festival. He gets a report indicating that  Scroggings: Well, the idea that Islam is responsible for the oppression of women is a very old idea in the West. It goes back hundreds of years. So it’s got a lot of roots here. So when somebody says that, it basically coincides with what people believe. So that’s one reason. I think with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, what really has made her so popular is her incredibly personal story. It’s very inspiring how she tells it. Her coming to the West. Becoming converted to Western ideas. Shaking off Islam. And then being threatened with death for speaking out against it. A lot of people feel very sympathetic to her and feel inspired by her because of that. So I think that’s really why she’s gained such an influential backing. And as to why she got named the 100 Most Influential People, that came right after the murder of Theo van Gogh. And I think it was sort of a sympathy vote on Time Magazine’s part. Because prior to all this, she was a very new junior legislator in the Dutch Parliament. Not somebody who would normally be considered one of the most influential people in the world.

Scroggings: Well, the idea that Islam is responsible for the oppression of women is a very old idea in the West. It goes back hundreds of years. So it’s got a lot of roots here. So when somebody says that, it basically coincides with what people believe. So that’s one reason. I think with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, what really has made her so popular is her incredibly personal story. It’s very inspiring how she tells it. Her coming to the West. Becoming converted to Western ideas. Shaking off Islam. And then being threatened with death for speaking out against it. A lot of people feel very sympathetic to her and feel inspired by her because of that. So I think that’s really why she’s gained such an influential backing. And as to why she got named the 100 Most Influential People, that came right after the murder of Theo van Gogh. And I think it was sort of a sympathy vote on Time Magazine’s part. Because prior to all this, she was a very new junior legislator in the Dutch Parliament. Not somebody who would normally be considered one of the most influential people in the world.

A few hours ago, I learned that

A few hours ago, I learned that

Salman Rushdie has turned in his last novel and resigned from PEN America to pursue a full-time acting career. He will be joining the cast of Entourage midway through its sixth season as a regular character named “Sal,” a burned out writer in his sixties who desperately tags along with Vince and his young cohorts in an effort to discover a new vitality.

Salman Rushdie has turned in his last novel and resigned from PEN America to pursue a full-time acting career. He will be joining the cast of Entourage midway through its sixth season as a regular character named “Sal,” a burned out writer in his sixties who desperately tags along with Vince and his young cohorts in an effort to discover a new vitality.

This year’s

This year’s

I am certainly not a fan of Salman Rushdie’s limitless capacity for self-promotion, but I am even less enamored of

I am certainly not a fan of Salman Rushdie’s limitless capacity for self-promotion, but I am even less enamored of