(This is the fourth entry in The Modern Library Nonfiction Challenge, an ambitious project to read and write about the Modern Library Nonfiction books from #100 to #1. There is also The Modern Library Reading Challenge, a fiction-based counterpart to this list. Previous entry: The Taming of Chance.)

One of the mistakes often made by those who immerse themselves in Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer is believing that MacDonald’s guilt or innocence is what matters most. But Malcolm is really exploring how journalistic opportunity and impetuous judgment can lead any figure to be roundly condemned in the court of public opinion. Malcolm’s book was written before the Internet blew apart much of the edifice separating advertising and editorial with native advertising and sponsored articles, but this ongoing ethical dilemma matters ever more in our age of social media and citizen journalism, especially when Spike Lee impulsively tweets the wrong address of George Zimmerman (and gets sued because of the resultant harassment) and The New York Post publishes a front page cover of two innocent men (also resulting in a lawsuit) because Reddit happened to believe they were responsible for the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.

One of the mistakes often made by those who immerse themselves in Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer is believing that MacDonald’s guilt or innocence is what matters most. But Malcolm is really exploring how journalistic opportunity and impetuous judgment can lead any figure to be roundly condemned in the court of public opinion. Malcolm’s book was written before the Internet blew apart much of the edifice separating advertising and editorial with native advertising and sponsored articles, but this ongoing ethical dilemma matters ever more in our age of social media and citizen journalism, especially when Spike Lee impulsively tweets the wrong address of George Zimmerman (and gets sued because of the resultant harassment) and The New York Post publishes a front page cover of two innocent men (also resulting in a lawsuit) because Reddit happened to believe they were responsible for the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.

Yet it is important to approach anything concerning the Jeffrey MacDonald murder case with caution. It has caused at least one documentary filmmaker to go slightly mad. It is an evidential involution that can ensnare even the most disciplined mind, a permanently gravid geyser gushing out books and arguments and arguments about books, with more holes within the relentlessly regenerating mass than the finest mound of Jarlsberg. But here are the underlying facts:

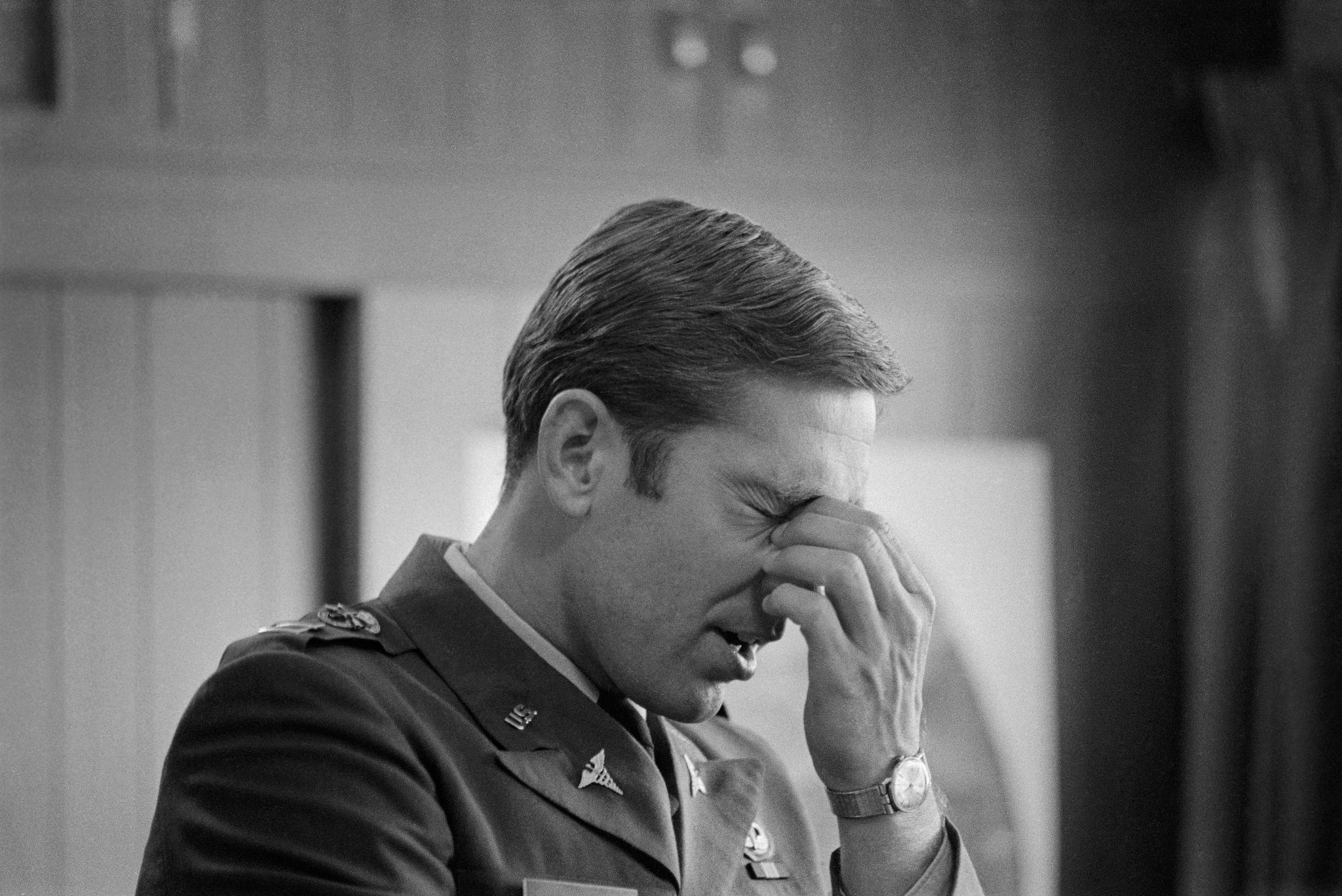

On February 17, 1970, Jeffrey MacDonald reported a stabbing to the military police. Four officers found MacDonald’s wife Colette, and their two children, Kimberley and Kristen, all dead in their respective bedrooms. MacDonald went to trial and was found guilty of one count of first-degree murder and two counts of second-degree murder. He was sentenced to three life sentences. Only two months before this conviction, MacDonald hired the journalist Joe McGinniss — the author of The Selling of a President 1968, then looking for a comeback — to write a book about the case, under the theory that any money generated by MacDonald’s percentage could be used to sprout a defense fund. MacDonald placed total trust in McGinniss, opening the locks to all his papers and letting him stay in his condominium. McGinniss’s book, Fatal Vision, was published in the spring of 1983. It was a bestseller and spawned a popular television miniseries, largely because MacDonald was portrayed as a narcissist and a sociopath, fitting the entertainment needs of a bloodthirsty public. MacDonald didn’t know the full extent of this depiction. Indeed, as he was sitting in jail, McGinniss refused to send him a galley or an advance copy. (“At no time was there ever any understanding that you would be given an advance look at the book six months prior to publication,” wrote McGinniss to MacDonald on February 16, 1983. “As Joe Wambuagh told you in 1975, with him you would not even see a copy before it was published. Same with me. Same with any principled and responsible author.” Malcolm copiously chronicles the “principled and responsible” conduct of McGinniss quite well, which includes speaking with MacDonald in misleading and ingratiating tones, often pretending to be a friend — anything to get MacDonald to talk.)

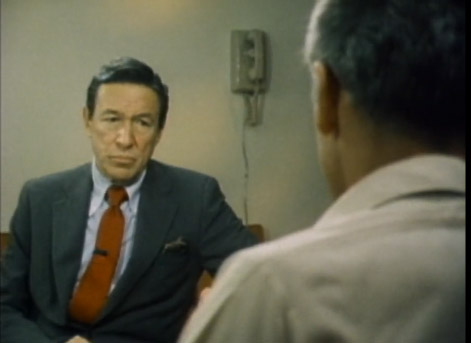

On 60 Minutes, roughly around the book’s publication, Mike Wallace revealed to MacDonald what McGinniss was up to:

Mike Wallace (narrating): Even government prosecutors couldn’t come up with a motive or an explanation of how a man like MacDonald could have committed so brutal a crime. But Joe McGinniss thinks he’s found the key. New evidence he discovered after the trial. Evidence he has never discussed with MacDonald. A hitherto unrevealed account by the doctor himself of his activities in the period just before the murders.

Joe McGinniss: In his own handwriting, in notes prepared for his own attorneys, he goes into great detail about his consumption of a drug called Eskatrol, which is no longer on the market. It was voluntarily withdrawn in 1980 because of dangerous side effects. Among the side effects of this drug are, when taken to excess by susceptible individuals, temporary psychosis, often manifested as a rage reaction. Here we have somebody under enormous pressure and he’s taking enough of this Eskatrol, enough amphetamines, so that by his own account, he’s lost 15 pounds in the three weeks leading up to the murders.

Wallace: Now wait. According to the note which I’ve seen, three to five Eskatrol he has taken. We don’t know if he’s taken it over a period of several weeks or if he’s taken three to five Eskatrol a day or a week or a month.

McGinniss: We do know that if you take three to five Eskatrol over a month, you’re not going to lose 15 pounds in doing so.

Jeffrey MacDonald: I never stated that to anyone and I did not in fact lose fifteen pounds. I also wasn’t taking Eskatrol.

Wallace (reading MacDonald’s note): “We ate dinner together at 5:45 PM. It is possible I had one diet pill at this time. I do not remember and do not think I had one. But it is possible. I had lost 12 to 15 pounds in the prior three to four weeks in the process, using three to five capsules of Eskatrol Spansule. I was also…”

MacDonald: Three to five capsules for the three weeks.

Wallace: According to this.

MacDonald: Right.

Wallace: According to this.

MacDonald: And that’s a possibility.

Wallace: Then why would you put down here that…that there was even a possibility?

MacDonald: These are notes given to an attorney, who has told me to bare my soul as to any possibility so we could always be prepared. So I…

Wallace: Mhm. But you’ve already told me that you didn’t lose 15 pounds in the three weeks prior…

MacDonald: I don’t think that I did.

Wallace: It’s in your notes. “I had lost 12-15 lbs. in the prior 3-4 weeks, in the process using 3-5 capsules of Eskatrol Spansules.” That’s speed. And compazine. To counteract the excitability of speed. “I was losing weight because I was working out with a boxing team and the coach told me to lose weight.” — 60 Minutes

One of McGinniss’s exclusive contentions was that MacDonald had murdered his family because he was high on Eskatrol. Or, as he wrote in Fatal Vision:

It is also fact that if Jeffrey MacDonald were taking three to five Eskatrol Spansules daily, he would have been consuming 75 mg. of dextroamphetamine — more than enough to precipitate an amphetamine psychosis.

Note the phrasing. Even though McGinniss does not know for a fact whether or not MacDonald took three to five Eskatrol (and MacDonald himself is also uncertain: both MacDonald and McGinniss prevaricate enough to summon the justifiably hot and bothered mesh of Mike Wallace’s grilling), he establishes the possibility as factual — even though it is pure speculation. The prognostication becomes a varnished truth, one that wishes to prop up McGinniss’s melodramatic thesis.

Malcolm was sued for libel by Jeffrey Masson over her depiction of him in her book, In the Freud Archives. In The Journalist and the Murderer, she has called upon all journalists to feel “some compunction about the exploitative character of the journalist-subject relationship,” yet claims that her own separate lawsuit was not the driving force in the book’s afterword. Yet even Malcolm, a patient and painstaking practitioner, could not get every detail of MacDonald’s appearance on 60 Minutes right:

As Mike Wallace — who had received an advance copy of Fatal Vision without difficulty or a lecture — read out loud to MacDonald passages in which he was portrayed as a psychopathic killer, the camera recorded his look of shock and utter discomposure.

Wallace was reading MacDonald’s own notes to his attorney back to him, not McGinniss’s book. These were not McGinniss’s passages in which MacDonald was “portrayed as a psychopathic killer,” but passages from MacDonald’s own words that attempted to establish his Eskatrol use. Did Malcolm have a transcript of the 60 Minutes segment now readily available online in 1990? Or is it possible that MacDonald’s notes to his attorney had fused so perfectly with McGinnis’s book that the two became indistinguishable?

This raises important questions over whether any journalist can ever get the facts entirely right, no matter how fair-minded the intentions. It is one thing to be the hero of one’s own story, but it is quite another to know that, even if she believes herself to be morally or factually in the clear, the journalist is doomed to twist the truth to serve her purposes.

It obviously helps to be transparent about one’s bias. At one point in The Journalist and the Murderer, Malcolm is forthright enough to confess that she is struck by MacDonald’s physical grace as he breaks off pieces of tiny powdered sugar doughnuts. This is the kind of observational detail often inserted in lengthy celebrity profiles to “humanize” a Hollywood actor uttering the same calcified boilerplate rattled off to every roundtable junketeer. But if such a flourish is fluid enough to apply to MacDonald, we are left to wonder how Malcolm’s personal connection interferes with her purported journalistic objectivity. In the same paragraph, Malcolm neatly notes the casual abuse MacDonald received in his mailbox after McGinniss’s book was published — in particular a married couple who read Fatal Vision while on vacation who took the time to write a hateful letter while sunbathing at the Sheraton Waikiki Hotel. This casual cruelty illustrates how the reader can be just as complicit as the opportunistic journo in perpetuating an incomplete or slanted portrait.

The important conundrum that Malcolm imparts in her short and magnificently complicated volume is why we bother to read or write journalism at all if we know the game is rigged. The thorny morality can extend to biography (Malcolm’s The Silent Woman is another excellent book which sets forth the inherent and surprisingly cyclical bias in writing about Sylvia Plath). And even when the seasoned journalist is aware of ethical discrepancies, the judgmental pangs will still crop up. In “A Girl of the Zeitgeist” (contained in the marvelous collection, Forty-One False Starts), Malcolm confessed her own disappointment in how Ingrid Sischy failed to live up to her preconceptions as a bold and modern woman. Malcolm’s tendentiousness may very well be as incorrigible as McGinnis’s, but is it more forgivable because she’s open about it?

It can be difficult for Janet Malcolm’s most arduous advocates to detect the fine grains of empathy carefully lining the crisp and meticulous forms of her svelte and careful arguments, which are almost always sanded against venal opportunists. Malcolm’s responsive opponents, which have recently included Esquire‘s Tom Junod, Errol Morris, and other middling men who are inexplicably intimidated by women who are smarter, have attempted to paint Malcolm as a hypocrite, an opportunist, and a self-loathing harpy of the first order. Junod wrote that “it’s clear to anyone who reads her work that very few journalists are animated by malice than Janet Malcolm” and described her work as “a self-hater whose work has managed to speak for the self-hatred” of journalism. Yet Junod cannot cite any examples of this self-hate and malice, save for the purported Henry Youngman-like sting of her one liners (Malcolm is not James Wolcott; she is considerably more thoughtful and interesting) and for pointing out, in Iphigenia in Forest Hills, how trials “offer unique opportunities for journalistic heartlessness,” failing to observe how Malcolm pointed out how words or evidence lifted out of context could be used to condemn or besmirch the innocent until proven guilty (and owning up to her own biases and her desire to interfere).

Malcolm is not as relentless as her generational peer Renata Adler, but she is just as refreshingly formidable. She is as thorough with her positions and almost as misunderstood. She has made many prominent enemies for her controversial positions — even fighting a ten year trial against Jeffrey Masson over the authenticity of his quotations (dismissed initially by a federal judge in California on the grounds that there was an absence of malice). Adler was ousted from The New Yorker, but Malcolm was not. In the last few years, both have rightfully found renewed attention for their years among a new generation.

One origin for the anti-Malcolm assault is John Taylor’s 1989 New York Magazine article, “Holier than Thou,” which is perhaps singularly responsible for making it mandatory for any mention of The Journalist and the Murderer to include its infamous opening line: “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible.” Taylor excoriated Malcolm for betraying McGinniss as a subject, dredged up the Masson claims, and claimed that Malcolm used Masson much as McGinniss had used MacDonald. It does not occur to Taylor that Malcolm herself may be thoroughly familiar with what went down and that the two lengthy articles which became The Journalist and the Murderer might indeed be an attempt to reckon with the events that caused the fracas:

“Madame Bovary, c’est moi,” Flaubert said of his famous character. The characters of nonfiction, no less than those of fiction, derive from the writer’s most idiosyncratic desires and deepest anxieties; they are what the writer wishes he was and worries that he is. Masson, c’est moi.

Similarly, Evan Hughes had difficulty grappling with this idea, caviling over the “bizarre stance” of Malcolm not wanting to be “oppressed by the mountain of documents that formed in my office.” He falsely infers that Malcolm has claimed that “it is pointless to learn the facts to try to get to the bottom of a crime,” not parsing Malcolm’s clear distinction between evidence and the journalist’s ineluctable need to realize characters on the page. No matter how faithfully the journalist sticks with the facts, a journalistic subject becomes a character because the narrative exigencies demand it. Errol Morris can find Malcolm’s stance “disturbing and problematic” as much as he likes, but he is the one who violated the journalistic taboo of paying subjects for his 2008 film, Standard Operating Procedure, without full disclosure. One of Morris’s documentary subjects, Joyce McKinney, claimed that she was tricked into giving an interview for what became Tabloid, alleging that one of Morris’s co-producers broke into her home with a release form. Years before Morris proved triumphant in an appellate court, he tweeted:

I prefer the truth with some varnish on it. (Where did that nonsensical phrase – the unvarnished truth – come from?)

— errolmorris (@errolmorris) July 18, 2010

The notion of something “unvarnished” attached to a personal account may have originated with Shakespeare:

And therefore little shall I grace my cause

In speaking for myself. Yet, by your gracious patience,

I will a round unvarnished tale deliver

Of my whole course of love. What drugs, what charms,

What conjuration and what mighty magic—

For such proceeding I am charged withal—

I won his daughter.

— Othello, Act 1, Scene 3

Othello hoped that in telling “a round unvarnished tale,” he would be able to come clean with Brabantio over why he had eloped with the senator’s daughter Desdemona. He wishes to be straightforward. It’s an extremely honorable and heartfelt gesture that has us very much believing in Othello’s eloquence. Othello was very lucky not to be speaking with a journalist, who surely would have used his words against him.

Next Up: Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood!

Plummer: There is an Everyman in Hamlet. And every member of the audience must, whether they like it or not, try to identify with him in this sense. And there is the chance in that extraordinary role of them being able to do that. Then there’s the remoter side of Hamlet, which is the urbane and the wit and the wisdom in one so young. And the style that perhaps takes him away from being identified, but particularly with modern audiences, who probably don’t know what style is. So it is such a melange of extraordinary qualities, Hamlet, that it makes the greatest role ever written. There is no doubt of that. And he must have also the great temper. He must possess the great temper in order to frighten the audience. He must have all sorts of qualities all in one. Because it’s written that way. It’s written as a great symphony of a part. And unless you obey the codas, the climaxes, and the stresses, musically, you’re not anywhere near finished playing Hamlet.

Plummer: There is an Everyman in Hamlet. And every member of the audience must, whether they like it or not, try to identify with him in this sense. And there is the chance in that extraordinary role of them being able to do that. Then there’s the remoter side of Hamlet, which is the urbane and the wit and the wisdom in one so young. And the style that perhaps takes him away from being identified, but particularly with modern audiences, who probably don’t know what style is. So it is such a melange of extraordinary qualities, Hamlet, that it makes the greatest role ever written. There is no doubt of that. And he must have also the great temper. He must possess the great temper in order to frighten the audience. He must have all sorts of qualities all in one. Because it’s written that way. It’s written as a great symphony of a part. And unless you obey the codas, the climaxes, and the stresses, musically, you’re not anywhere near finished playing Hamlet.