Thomas Frank appeared on The Bat Segundo Show #428. He is most recently the author of Pity the Billionaire.

Listen: Play in new window | Download

Condition of Mr. Segundo: Wondering why Grover Norquist keeps leaving voicemails about tax pledges.

Author: Thomas Frank

Subjects Discussed: House Majority Leader Eric Cantor’s notion of “compromise,” the Republican failure to acknowledge Reagan’s complete history, Reagan’s Continental Illinois bailout, efforts to “erase” liberalism from Washington, Barack Obama’s failings, Congressional disapproval by the American people (as reflected by recent polls), how George W. Bush became a toxic Republican figure, the Tea Party movement, the Great Recession, how the Right co-opted populism after 2008, the 2010 extension of the Bush tax cuts and Bernie Sanders’s filibuster, Obama signing the NDAA “with serious reservations,” the Democratic Party less about the working man and more about expertise and technocrats, Obama’s TARP bailouts vs. Roosevelt’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation bailouts, government agencies that become instruments of Wall Street, “purified” capitalism, firing bank managers, conservatives mimicking progressive ideologies of the past and protest movements of the 1930s, co-opting outrage, Orson Welles’s influence on Glenn Beck, The War of the Worlds, being subscribed to Beck’s email newsletter, Jack Abramoff, Grover Norquist, the Republican base being united over the past few decades by “quasi-military victory” and lack of civility, Howard Phillips and “organized discontent,” why the Democrats are allergic to discontent and anger, Roosevelt’s tendency to stump and explain legislation vs. Obama’s failure to do so, the Democratic tendency to use experts as a selling point, Jon Stewart and the New Political Privilege, the Rally to Restore Sanity, Occupy Wall Street, blue-collar invisibility in DC, living in a neighborhood in which 50% of the population have PhDs, NASCAR, idiosyncratic hangover cures, diffidence and resistance against righteous indignation in the last few years, the hard times swindle, Scott Walker and attacks on the Wisconsin labor movement, attempts to investigate why liberalism can’t stick in recent years given The Wrecking Crew‘s suggestion that people inherently expect a liberal state, the myth of small business job creation (specific data breakdown on new jobs creation from 1992-2008 from Scott Shane discussed by Correspondent and Frank), George Lucas calling himself an “independent filmmaker,” C. Wright Mills’s White Collar, small business serving as a propaganda front for big business, America’s reticence in discussing how we are all corporate slaves in some sense, Tea Party memorabilia, Glenn Beck’s CAPITALISM painting, Rep. Nan Hayworth’s dodging questions about Verizon with empty utopian bluster, whether it’s possible to take back the term “small business,” the Black Panther Party, ways to organize political movements, whether it’s possible to build a dedicated base to combat a corrupt two-party system, legal blockades to third party movements, protesting out of resentment and self-pity, self-pity and the resurgent Right, whether the Tea Party is protesting with a shared sense of humiliation, populist politics as a gateway drug, searching for good things to say about the Tea Party, liberalism and populist movements, Atlas Shrugged, Walter Issacson’s Steve Jobs biography, Jobs being selfish with his money, why selfishness is a uniquely American draw, retreating into laissez-faire purity, Ayn Rand’s prose style, capital strikes as fantasy, leftist versions of Atlas Shrugged, John Dos Passos, Steinbeck, Frank’s collection of proletarian fiction, Upton Sinclair, the cold sex and descriptions of steel and machinery in Atlas Shrugged, the connections between recent political movements and mythology, German sociologists from the 1930s, the social construction of reality, Karl Mannheim’s Ideology and Utopia, how the Left might find political possibilities in passion, pragmatism, and anger, the neutered Left falling prey to forms of mythology that are just as nefarious as present myths on the Right, organized labor, Steven Greenhouse’s The Big Squeeze, how politics tends to inspire perverse behavior, and train wrecks.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: We’re talking only a few nights after a really fascinating 60 Minutes interview with [House Majority Leader] Eric Cantor. I’m not sure if you saw this.

Correspondent: We’re talking only a few nights after a really fascinating 60 Minutes interview with [House Majority Leader] Eric Cantor. I’m not sure if you saw this.

Frank: I didn’t see it.

Correspondent: Well, it was interesting. Because it reminded me very much of your book. I’m about to talk with you and this happens. So [Cantor] appears. And it’s this fairly amicable, typical segment. And then Lesley Stahl basically says, “Will you compromise in any way?” And he dodged the issue of being able to compromise on anything. And then Lesley, of course, brings up the Reagan tax increase.

Frank: The 1986?*

Correspondent: Yes. And he denies that Reagan ever did that. And then, to add an additional monkey wrench into this, there’s an off-camera press secretary who says that’s a lie. And then, of course, they play the clip.

Frank: What?

Correspondent: Yes! And they play a clip of Reagan using “compromise” as a verb** when he’s talking about this tax increase. So this seems a very appropriate beginning to some of the issues in your book.

Frank: That’s amazing. That’s exactly what I’m writing about. These people who are essentially blinded by ideology. But when I say it that way, it sounds like some kind of slang term. Or something like that. But I mean it in a very serious way. That these are people who have bought an entire utopian way of seeing the world and are able to close their eyes to things that are obvious. And what you just said about Reagan, that would be a juicy detail that I would have loved to have had for the book. But there are so many other examples — essentially, they deny. Look, I went to a graduate school and studied history. One of the baseline things that historians agree on is that for the last thirty or forty years, we’ve been in a conservative era. That people around the world — governments, politicians, elites around the world — have discovered the power of markets and have moved in this direction towards markets that are deregulated, have privatized, have done all these things. This is common knowledge. A conservative movement today — you talk to a guy like Eric Cantor? No, that’s never happened. We’re still living under socialism. And we have been since Woodrow Wilson. Or something like this.

Correspondent: But why is it that Cantor and the Freshman Republicans want to just keep their blinders on about history? About their man Reagan? Is there a specific…

Frank: They have to have a hero and they’ve thrown George W. Bush under the bus. Because of the bailouts. But at the end of the day, look, it’s opportunism. Reagan is very popular. Bush is not popular. Nixon is not popular. So they have to have a hero. And it has to be someone who is beloved. Ipso facto, it has to be Reagan. But they have to deny all sorts of thing about Reagan. For example, Reagan bailed out Continential Illinois Bank — at the time, the biggest bank failure in U.S. history. Reagan, as you’ve just mentioned, raised taxes. Reagan sold weapons to Iran. You remember that one? Iran-Contra. I mean, there are all sorts of other crazy things that Reagan did that don’t look so good. I mean, Reagan really liked Franklin Roosevelt. Reagan was a more complicated person. But none of that is admissible. If you’re going to follow this ideology and this utopian vision that they have of what I call “market populism” — if you’re going to follow that all the way — and, of course, part of the idea of this is that you’re going to have to follow it all the way — and we’ll get into that a minute — you basically have to whitewash history. I mean, it’s almost Soviet, what you’re describing.

Correspondent: The phrase you use in The Wrecking Crew. “The Washington conservatives aim to make liberalism not by debating, but by erasing it.” And I’m wondering if there’s any past political precedent that would suggest they could entirely efface liberalism from our political machinations.

Frank: Or from our memory.

Correspondent: Or from our memory. It’s very strange.

Frank: Well, that was the big subject a few years ago — when The Wrecking Crew was published. One of the topics of conversation was these grand schemes that the Republicans kept coming up with. The Republicans in Washington here, I’m talking about. I’m not talking about your rank-and-file Republicans. But the Republicans in Washington kept coming up with the grand schemes for some kind of political checkmate. Some kind of move that would end the debate forever and yield victory for their side forever. And they include — privatizing social security was a big one. Another one — the one that I focused on in The Wrecking Crew — is deficits. And that, I’m sorry to say, I turned out to be right about the one. By deliberately running up the deficits in the Bush years, it doesn’t give them permanent victory, but it does stay the hand of whoever, whatever liberal follows — in this case, Barack Obama — and it has worked exactly as they planned it to. Although Obama pushed it a little farther than they thought possible with the stimulus package. But now look at what’s happened with the debt ceiling catastrophe and all that sort of thing. So that turned out to be effective. They were able to limit the debate by some deeds that they pulled while they were still in power. And some of the other things that they are trying or will try or I predict they’ll try, they are things about tricking the franchise. Somehow keeping or dissuading people from voting. That sort of thing. But there’s always this search for the doomsday device. Yes, and it still goes on.

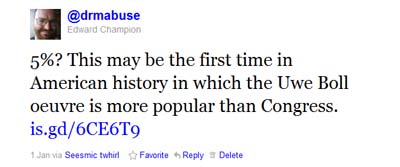

Correspondent: But this level of no quarter, no compromise. I mean, isn’t there some kind of “uncanny valley” or Hubbert’s Peak to what they can do before it’s just not acceptable? I mean, there was that latest Rasmussen poll where Congress got a 5% approval rating. That was a few days ago.

Correspondent: But this level of no quarter, no compromise. I mean, isn’t there some kind of “uncanny valley” or Hubbert’s Peak to what they can do before it’s just not acceptable? I mean, there was that latest Rasmussen poll where Congress got a 5% approval rating. That was a few days ago.

Frank: 5%?

Correspondent: 5%.

Frank: Well, that makes a difference in the Presidential Election. But that really won’t make a whole lot of difference, strangely enough, in the Congressional Election. Because people might hate Congress, but they like their own Congressman. That’s the classic, the old saw. But, look, what you’re getting at is a really interesting phenomenon of these people, instead of being pulled to the center — as all of your political science theorizing and all of your DC punditry insists that the gravity of politics pulls people to the center. Political scientists have believed this for fifty years. And this is a pet peeve of mine. Because I think it’s rubbish, okay, for reasons that we’ll go into. But it’s been just dramatically disproven in the last couple of years. Think back to 2008. You had the Republican Party in ruins. You had all these scandals in the Bush Administration. All this corruption. And then it ends with this catastrophic meltdown in the market. The housing bubble bursts. The banks start to go under, one after another. Then Wall Street starts shedding 700 points per day. It’s this crazy disaster. The financial crisis. And then they do the bailouts, forever sealing Bush’s fate not only with the general public but with the Right. One of the most unpopular Presidents of all time. The Republican Party is in ruins in 2008. And you have pundit after pundit weighing in and saying, “These people are done for. Bush led them too far to the right.” The era of George W. Bush was where they went too far to the right, and Tom DeLay and all those guys, they went too far to the right, and now they have to make their way back to the center or they will risk being irrelevant forever more. Or for the next twenty years or something like that. And look what happened. They did the opposite. Guys like Eric Cantor, they did not embrace the moderates in their party. They excommunicated them. They purged them. I mean, these guys, they behave like Communists in a lot of ways. This is one of those things. They purged these guys. They throw people out. And they don’t want them in the Party anymore. And they moved deliberately to the right. Way to the right. That’s what the Tea Party movement is all about. And I’ll be damned if it didn’t work. They just scored their biggest victory in eighty years. Or seventy what — a whole lot of years in the 2010 off-term elections. They had a huge victory. So obviously that strategy has vindicated for them. It worked! It paid off! And there’s no reason why they would go back on something that just succeeded. It was a success.

Correspondent: But in the chapter in this book, “The Silence of the Technocrats,” you describe this collapse of Democratic populism from 2008. You point to the failings of the Democrats to challenge the Tea Party, people at the town hall meetings. You point also to the manner in which they formed corporate alliances with healthcare and also the bailouts that we were just talking about. The failure of the stimulus package. The list goes on. Only a few days ago, Obama signed into law the NDAA, which essentially gives the government the right to detain any citizen, and he had this whole “with serious reservations” claause that he did while he signed it. So the question I have is: if Democrats are offering the defense that Obama is being forced into this predicament…

Frank: They’re listening to the pundits. The Republicans did the opposite of what the pundits suggested. The Democrats are listening to them. There’s this DC elite that the Democrats are listening to. This is what Obama’s Presidency is all about — it’s looking for a grand compromise. But the Republicans, they’re not interested. Make him come to us, they say. He can come to us. He can compromise in our direction. Look, at the end of the day, this is something you can figure out with game theory. It’s really simple. If they’re the side that stands pat and makes the other guy come to them, they win. But that’s neither her nor there. I think the Democrats really misplayed the hand they were dealt with. I mean, misplayed it in a colossal manner. In a catastrophic manner. And Obama may well get re-elected in 2012 at this point. Who knows at this point?

Correspondent: Well, with the crop of candidates, it’s a big clown car.

Frank: Elected for what purpose? After what’s happened, why bother? They didn’t understand the needs of the moment. The cultural and political needs of the moment, which were populist. They didn’t understand that all that political science theorizing that I was telling you about, where the center is where the gravity always pulls you — you have to move to the center. You have to make compromises with the other side. That all of that old way of thinking about everything was discredited. The financial crisis. The Great Recession. The huge business slump. We were going into Great Depression II, it looked like back then. And what was called for was 1930s style politics. The conservatives offered it. The Republicans offered it. Or I should say the Tea Party offered it and has since grafted it on the Republican Party. And the Democrats behaved as if everything was just as it was in the 1990s. That if they acted like Bill Clinton, everything would be fine. They did not understand that the old scheme was completely out the window.

Correspondent: Why though would they continue to act as if they wished to rise above partisanship? This notion…

Frank: That’s who they are.

Correspondent: I mean, even after the whole debt ceiling showdown. That whole business.

Frank: Can you believe that? Don’t you think that that would be the big convincer?

Correspondent: But why do you think this is? I mean, why didn’t Obama just go to the people and say, “Look, this is going to have serious actions even if I approve it or veto it. I am actually going to you, the American people, and I am explaining to you that the Republicans want to throw the Bill of Rights into a flaming trash can…

Frank: (laughs)

Correspondent: “So I can’t in good conscience sign this.” Why do you think he can’t do that?

Frank: Well, the point where this really got out of hand — I mean, there were several big turning points in the Obama Presidency, but the one that really just blew my mind because it was such a misplayed moment. And we think Obama’s a very intelligent man. And he is. I met up. He’s a super-duper smart guy. But some of the political moves have just been total rookie mistakes. The one that got me was when he still had a Democratic Congress. It was a lame duck session. This would have been at the end of 2010. And he renewed the Bush tax cuts. Why not make the Republicans come to him and offer something in exchange for that? No. He just gave it to them. It’s like the biggest prize on the table. And he just handed it over.

Correspondent: Leaving Bernie Sanders to do that long filibuster. But that ended up being all for nought. Even though it was an impressive theatrical display. Everybody was behind Bernie Sanders. Finally somebody standing up.

Frank: Oh sure. But it wasn’t up to Bernie Sanders. It was up to Barack Obama. And he just gave it away — the one ace he had in the hole, he just gave it away. And so maybe he did it as a good faith gesture to the Republicans. And look what it got him? This terrible smackdown with the debt ceiling crisis.

Correspondent: An embarrassment.

Frank: The kind of naivete that that takes. To not understand that that’s how these guys play the game. There’s plenty of journalists that wrote about the DeLay Congress and the Gingrich Congress. We know how these guys play. Or George W. Bush. Look at the career of Karl Rove. These guys play to win. They don’t mess around. And the innocence of Washington that it took to make a blunder — let’s call it what it is. A blunder like that is shocking to me.

Correspondent: If he’s so smart, why does he constantly come to them? I mean, why give the game away like that?

Frank: Because that’s who they are. That’s the Democratic Party nowadays.

Correspondent: It’s been like that for a while though, you know?

Frank: It has. And, hey, let’s be fair. Obama isn’t the — all of their last six Presidential candidates have been cut from the same cloth. I think Obama is, in lots of ways, smarter and a better speaker, and more talented than a lot of their previous leaders. But this is who the Democratic Party has become. Many years ago, they were the party of the working man. Everyone knew that. They were also a party that had an ideology. An ideology that arose from organized labor, that arose from the New Deal. And that has been lost. They are the party of technocrats now. Look, everything I’m telling you right now is right on the surface down at Washington DC. The big Democratic Party thinkers talk about this all the time. We are the party of the professional class. And if we aren’t that yet, that’s who we’re going to be when we’re done. We’re going to get there eventually.

* — This is a very pedantic stickler point, but one that nonetheless demands clarity. Reagan raised taxes twelve times during his administration. Frank is referring to the Tax Reform Act of 1986. But, to be clear, Stahl was specifically referring to Reagan’s 1982 tax increase in the 60 Minutes segment.

** — Another highly pedantic (and perhaps needless) stickler point. Reagan used “compromise” as a noun, not as a verb: “Make no mistake about it, this whole package is a compromise.” And while Reagan’s specific words convey the same point (indeed more definitively with a noun), it is important to remain committed to painstaking accuracy — especially when the corresponding approach being discussed over the hour involves how political parties cleave to mythology.

The Bat Segundo Show #428: Thomas Frank (Download MP3)

This text will be replaced