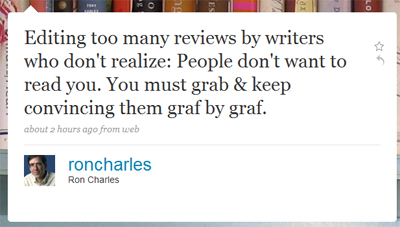

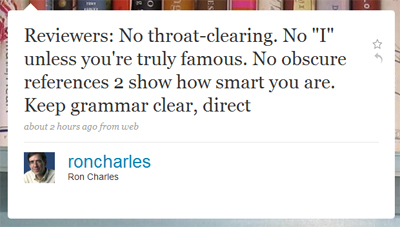

On the morning of July 21, 2009, Washington Post books editor Ron Charles expressed some concerns about book reviewers on Twitter:

At the risk of clearing my own throat (and with all due respect to Mr. Charles), I’m wondering if the 2008 winner of the Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing really has a handle on the type of writing that is likely to attract readers to his newspaper section.

Mr. Charles’s editorial sensibilities call for clear and direct writing. But his other entreaties are problematic. He asks that a first-person perspective or a sense of playfulness through reference — vital variables that might permit readers to get excited, interested, or enthused about a book — be omitted from the equation. Mr. Charles cannot seem to corral the idea of grabbing an audience with each graf with the possibility that readers may be interested with what a particular voice has to say (see, for example, the rise of litblogs over the past six years). Indeed, if Mr. Charles is desirous of a more objective journalistic approach, should not the ideal reviewer be someone who permits a reader to make up her own mind? Mr. Charles’s sentiments appear to reflect a newspaper culture in which personality or perspective — those indelible human traits that make us interested in people on so many levels — don’t get a hot seat at the formal table. Unless, of course, the reviewer is “truly famous,” which connotes a troubling elitism that runs counter to Mr. Charles’s seemingly egalitarian-minded agenda.

We should probably ask ourselves whether there is even a “general audience” for books. I think a case can certainly be made, provided you keep in mind that a “general audience” doesn’t just consume the type of pretentious literary fiction involving suburban asshats and cricket bats. We have seen millions of people get excited over the Harry Potter books (and their cinematic counterparts; see the box office bonanza in the past week). As I discussed with Sarah Wendell and Candy Tan in a recent podcast interview about the romance genre, over 64 million people claimed to read a romance novel in 2004. If Mr. Charles is genuinely committed to a “general audience,” surely he would open up his books section to more romance coverage. (Certainly, Mr. Charles’s coverage of Nora Roberts is a start.) And if the Washington Post is sincerely devoted to attracting a “general audience,” they may wish to do away with the annoying and obtrusive registration prompts that pester us for personal information.

But let’s examine a typical lede for a Washington Post review. Let’s take, simply at random, the first fiction review on today’s Washington Post books page: Mke Reed on Colum McCann’s Let the Great World Spin. Here’s the lede:

As the narrator of Colum McCann’s new novel sees it, Philippe Petit’s tightrope walk between the World Trade Center towers in 1974 triggered a quietude generally unknown to New Yorkers.

We can do away with the superfluous opening clause. There’s no need to inform the reader that this is a review about Colum McCann’s latest book. We already know this. So this leaves us with:

Philippe Petit’s tightrope walk between the World Trade Center towers in 1974 triggered a quietude generally unknown to New Yorkers.

Okay, we have a few interesting concepts to play with here. There’s the exciting prospect of Philippe Petit’s tightrope walk, which is rendered remarkably cold and objective through the bland reportorial phrasing. There’s the more intriguing concept of “triggered a quietude generally unknown.” That phrasing is clumsy, hardly as “clear” and “direct” as Mr. Charles demands. (Is the “triggering” a reference to 9/11? Were New Yorkers really quietly in awe for the first time in 1974?) But there’s some poetic potential here. Perhaps if we take the metaphor and front-load it at the beginning of the sentence, we might have a more compelling lede:

His high wire walk between the twin towers triggered an explosive awe among New Yorkers.

Okay, this isn’t perfect, but it’s an improvement. If the reader is unfamiliar with Petit (or familiar with the 2008 Petit documentary Man on Wire), she’ll be compelled to move onto the next sentence. By switching “tightrope” to “high wire,” we not only provide cultural context for a reader (“Hey, isn’t that the Man on Wire documentary?”) who soaks up art more from cinema than from books, but we also neatly foreshadow the “explosive trigger” metaphor later in the sentence. (Do you cut the red wire or the green wire?) By removing the subjective “generally unknown” assumption about New Yorkers, we do away with a superfluous aside that has little to do with the paragraph’s main purpose here.

With a few modest editorial changes, not only do we have a lede that is more of interest to a general audience, but we also don’t insult the audience’s intelligence by littering their attentive bin with the detritus of clinical phrasing.

Of course, one can avoid these disastrous results by daring to write in the first-person. Ernest Hemingway once wrote an essay about writing in the first-person — which can be found in A Moveable Feast — in which he suggested, “When you first start writing stories in the first person, if the stories are made so real that people believe them, the people reading them nearly always think the stories really happened to you.” Hemingway was referring primarily to fiction, but the advice nevertheless points to one primary deficiency among the newspapers — namely, an ability to give the reader a sense that he is a colleague, not some peon to be dictated to, and that literature is something to be experienced rather than cheerlessly discussed over tea and scones.

Correspondent: You also bring up one moment in the book, where you depict Senator John Stennis — the man, of course, who wrote one of the first Senate ethics codes; in fact, the first Senate ethics code. And who had not raised more than $5,000 for all of his campaigns in the past. Now here he is up for reelection in 1982. And he needs to raise $2 million. He is now forced to accept this devil’s bargain. This leads me to wonder whether, in fact, there is even room for a Sam Rayburn type of Congressman anymore. Whether it’s even possible for someone of any ethical core to be in this deeply ingrained system. If John Stennis can’t do it, then who can?

Correspondent: You also bring up one moment in the book, where you depict Senator John Stennis — the man, of course, who wrote one of the first Senate ethics codes; in fact, the first Senate ethics code. And who had not raised more than $5,000 for all of his campaigns in the past. Now here he is up for reelection in 1982. And he needs to raise $2 million. He is now forced to accept this devil’s bargain. This leads me to wonder whether, in fact, there is even room for a Sam Rayburn type of Congressman anymore. Whether it’s even possible for someone of any ethical core to be in this deeply ingrained system. If John Stennis can’t do it, then who can?

Even though I have yet to hear back from Marcus Brauchli

Even though I have yet to hear back from Marcus Brauchli