Can a woman seeking a $1,500/month guardian stipend truly afford to stay at a New Jersey motel for several weeks? (The Quality Inn in Toms River, New Jersey has kindly informed me that they rent rooms at $39.95/night. Discounting tax, that’s $279.65/week. At three weeks, that’s $838.95.) I suppose she could put it on her credit card, even though she’s just spent a considerable amount of her money in rehab and doesn’t appear to be gainfully employed. But can this same woman also afford to retain an attorney who makes at least three public appearances?

If a pack of cigarettes cost about eight bucks in Jersey, and you are a spendthrift like Mike Flaherty (played by Paul Giamatti), does it make any sense to buy a fresh pack, throw the other nineteen cancer sticks into a dumpster, and then smoke the remainder whenever you need to relieve stress? (For that matter, why are you spending your money on mid-grade scotch you keep in the office? And if your cigarette intake is that why aren’t you relieving stress that way?)

Such story problems emerge up with troubling frequency during Win Win, which isn’t just a subpar mainstream comedy, but a fallacious fantasy. The vastly overrated writer-director Thomas McCarthy (not to be confused with the very smart British novelist Tom McCarthy, who gave us Remainder and C) hasn’t bothered to ask or answer these basic questions. Perhaps it’s because McCarthy lives in a privileged bubble which prevents him from researching or investigating the very people he wishes to depict.

If we are to (rightly) condemn the Tea Party for perpetuating the view that some mythical age of prosperity occurred under Reagan, then we should also (rightly) condemn any huckster who wishes to perpetuate a roseate view of the middle-class instead of one that accurately presents its ongoing erosion (yet still manages to get us to walk away with some faith in humankind: Stewart O’Nan’s novels or Mike Leigh’s films come very much to mind). Because of these problems, Win Win is more feel-good propaganda than respectable entertainment. It’s the kind of movie that a clueless centrist, the type who doesn’t know how to live and who arrogantly claims comprehension of the hoi polloi without actually talking with them, will enjoy without question. I know this, because the film’s generic and gutless humor (1980s rock stars, games called Secret Apprentice, signs on ceilings that read “If you can read this, you’re pinned”) caused the middle-class types I was sitting with to laugh at the carefully engineered, preprogrammed moments.

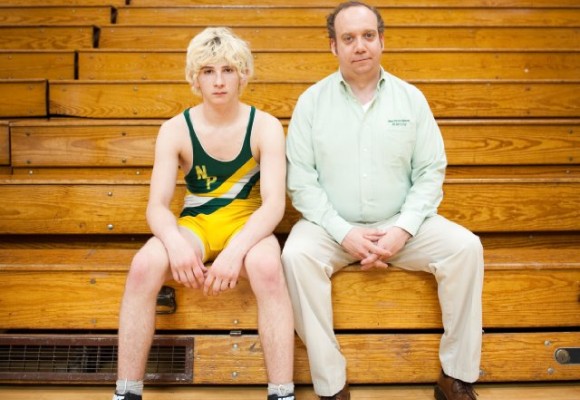

The problem here may be that Win Win is actually two movies awkwardly sandwiched into one. Does it want to be a film about how Mike Flaherty survives in an increasingly unforgiving economy as a sole practitioner who takes up the causes of the elderly and as a part-time wrestling coach? Or a film about how a man who cannot relax finds a new cause to take up with Kyle (Alex Shaffer)? Kyle, a troubled boy, reveals himself to be a very capable wrestler who can shake the wrestling team from its losing streak. (Some hint of Kyle’s troubled past is seen late in the film, where Kyle’s violence shows signs of surfacing to the edge. Between this, and one joke that has Mike hitting Kyle in the face just before a wrestling match, there’s the possibility of a richer film buried beneath the crowd-pleasing claptrap. Alas, McCarthy would prefer to collect the check.) He’s landed into Mike’s life not long after Mike has taken the aforementioned $1,500 monthly guardian stipend from Kyle’s grandfather to help keep his family afloat.

Because the film’s story is so overstuffed, supporting characters who should matter aren’t given the chance to breathe. Amy Ryan, for instance, plays Jackie, Mike’s wife, revealed to be nothing less than a former Jersey girl (with a JBJ tattoo on her ankle: JBJ, of course, being shorthand for Jon Bon Jovi, a shorthand that also condescends to the audience) who now nurtures. The Flaherty family may be having financial difficulties, but why doesn’t the family chip into pick up the slack. Why doesn’t the film give Jackie a chance to get a part-time job? Or even offer us a dramatic moment in which Mike finally cops to Jackie about his inability to make ends meet? Surely, a woman who has observed her husband cheaping out (not fixing the creaky pipes in the office, not sending in the health insurance check on time, not hiring a tree surgeon to cut down the diseased tree) would notice. Even Mike’s office assistant, a woman confident enough to announce her hangovers and carefully tallying the expenses, would probably have some modest clue that the arithmetic doesn’t add up. Presumably, these women don’t confront Mike with these financial issues because they are aware of Mike’s health (he hyperventillates after too much stress). But if Mike has the time to work two jobs, and he’s spending nearly all of his spare time playing Wii tennis and bullshitting with his somewhat loutish friend Terry (Bobby Cannavale), surely he should take some personal responsibility or would at least be called (gently perhaps) on the way he evades what he needs to do. I mentioned a woman earlier who also cannot do the financial numbers. That woman is Kyle’s mother. So that’s three women McCarthy offers who are incapable of understanding basic personal finance. In a world in which The New York Times claims gang rapists to be the victims, I don’t think it’s hyperbolic to call Thomas McCarthy a sexist pig.