Here’s how The Literary Encyclopedia’s entry on Tom McHale begins:

In the 1970s, Tom McHale established himself as one of the most promising American novelists of his generation. In a little more than a decade, he produced more than a half-dozen novels that were widely reviewed. Most of those reviews were enthusiastically–sometimes wildly–positive. But even those reviewers who were more guarded in their responses to the individual novels acknowledged the originality of McHale’s darkly comic vision, the engaging energy of his style, and the evidence of a considerable talent in the growing body of his work. Reviewers compared his novels to those of Joseph Heller, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., John Updike, Philip Roth, and Bruce Jay Friedman. In 1972, McHale’s second novel, Farragan’s Retreat was named a finalist for the National Book Award, and two years later McHale was the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship for Fiction. A New York Times article on the current literary scene placed McHale with Don DeLillo in the vanguard of those novelists who were most influential in terms of the directions that the American novel would take in the 1980s.

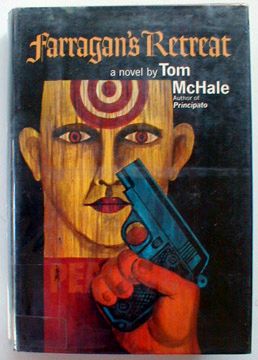

I always want to remember Tom McHale as that dashing young guy on the back cover of my much thumbed-through Literary Guild hardcover copy of his second novel Farragan’s Retreat, the one I first read when I was still a teenager. I was blown away by the black humor and Tom’s elegant style.

Here’s how the Time Magazine review from March 1, 1971 begins:

The old motto, “Power perfected becomes grace,” could have been invented to describe Tom McHale’s novels about Irish and Italian Catholics in America. Humor is his forte—not satire but farce. No aberration is too grotesque to be included, no character too minor to be lampooned. McHale’s comedy waves over chaos like luxuriant grass over a grave.

There are many young writers with healthy reserves of rage and chaos, some indeed with little else. What distinguishes McHale is not only the fertility of his invention but the humanity—remarkable in a writer of 28—that penetrates even his crudest caricatures.

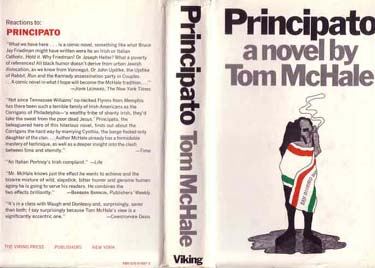

After I finished Farragan’s Retreat, I went to the library to find Tom’s first novel, Principato. (Thanks to Matt St. Amand for the review. Matt knows Tom’s work better than just about anyone.) I loved it as well.

Then I read Farragan’s Retreat again. I copied out passages. In the first story I ever wrote for my MFA program, I stole Tom’s description of “the hilltop hulk of the art museum along the Schuykill” for a section where my protagonist, a Penn student, takes her morning jog. (People “jogged” in the 70s.)

Later I’d meet Tom McHale at The Book Group of South Florida, founded in the early 1980s in what was then something of a literary wasteland. I can recall how astonished Tom was when we first met and I could quote his work back to him. I suppose he hadn’t recently encountered people who knew his work.

The last job Tom had before he died was was night assistant at the $1.50 Holiday movie theater in North Miami Beach. He got fired for absenteeism; Tom drank a lot at the end, maybe for years. It never occurred to me that he was an alcoholic, but then I’ve never had a drink im my life and am bad at recognizing drunks.

On Matt St. Amand’s website, he quotes from a rather inartful and self-serving letter from me:

Do you know that after he committed suicide in his sister’s garage about two miles from where I am sitting, I was asked to speak at his memorial service because, the person said, “You were his best friend, weren’t you?” when in reality, I was just an acquaintance of Tom. It was so sad. Tom and I met, I guess around 1981, as part of the Book Group of South Florida. Most of the people there were old ladies who’d been in publishing. Tom was amazed I’d read all his books and could quote lines from Farragan’s Retreat. He’d had a really rough time of it by that time, and he finally had another book coming out. I remember his publication party at the tony Bay Harbor Islands. I always feel uncomfortable at these things, and it was clear to me that most of these people were just society types or people on the make who had no idea who Tom was or his place in American literature. I left early, stopped off for a couple of errands, and then went to a Burger King to get a Whopper. I was shocked to see Tom sitting there alone, just after he’d been the guest of honor at his publication party. I guess at that moment I sensed how lonely he was, and I sat with him, and I guess it was really the only time I really talked to him, and even then, he was pretty stoic and reticent.

He got a horrible review from Ivan Gold, who’d had his own problems with writer’s block and alcohol, in the Sunday NY Times Book Review, and I know that depressed him. But I don’t know what caused him to take his life. His very Catholic family (siblings) were, I suspect, always somewhat uncomfortable with Tom. I never talked to his sister. The newspapers asked me for comments about his death, and I said stupid things. A year later, I had a book reviewed in the NY Times Book Review, also by Ivan Gold, and it was a mostly nice review, but the niceness was spoiled by how Gold’s review had hurt Tom.

We never did have a Book Group memorial service. Tom was 40 when he died, in the garage of his sister’s house in Pembroke Pines.

Here’s how “Portrait of a Writer as a Young Suicide,” a July 4, 1982 Miami Herald article by Cathy Lynn Grossman ends:

Nedda Anders, founder and president of the Book Group and editor-publisher of Andiron Press Inc. in Tamarac, introduced the subject of McHale:

“At the last meeting there was a post-mortem on our lovely party for Tom McHale. Now, this meeting, we have a post-mortem on Tom himself. His sister asked us to do nothing more.”

It was the group’s regular meeting, complete with sandwiches from the deli. They sat on plastic chairs at fake wood tables in the Community Room of a pillbox branch bank building dropped incongruously into the scrub brush along University Drive in Lauderhill. All that could be seen from the windows were cars shimmering in the heat, transplanted trees and transient commerce.

“I know I told you it was a heart attack,” Anders said. “That’s what his sister said. I guess, for reasons of her Catholicism … she told me that and I told you that it was a heart attack, but anyone who commits suicide has had heart failure so I wasn’t really lying.”

They passed around a copy of the paragraph in Time magazine, mentioning the death of the author “by his own hand” and a short obituary from a newspaper. Everyone said,”tsk-tsk.”

Everyone: A retiree who has established himself in Hollywood as a literary consultant. Some delicate older women writing articles for magazines or the story of Davie. A librarian. Several one-person publishing companies producing books on health, astronomy or local memoirs and history. A short-story writer, Richard Grayson, who succeeded the late McHale as the most famous member of the group, which was then planning a party for Grayson’s second book, Lincoln’s Doctor’s Dog.

People each said how they met McHale, how little they knew him, adding the few facts they had.

“There seemed to be no barriers in Tom,” Anders said. “He was crisp and charming. … We are trying to cope.”

Literary agent Myra Gross remembered that he had landed “a real plum” of a teaching job for next September at the University of Pennsylvania.

Anders interrupted, saying, “He seemed so perfectly equal to life, so absolutely rational. It’s hard to think that somewhere in him was hidden something irrational. … Myra’s son used to call him a ‘cool guy.’ ”

“Cool dude,” Myra Gross corrected her.

During lunch they talked about Mchale’s funny books on guilt, his angry, anti-religious attitudes and the irony of his Catholic funeral in a faith that denies its rituals to suicides.

“It is so terribly difficult to know what drives people, especially writers,” said the author of romances.

“Gee, I wish he’d talked to me,” said the retired consultant.

“His books were getting increasingly less attention,” Grayson said. “Ten years ago you could write literary books and make money. Not now.

“After Tom’s publication party, when I was driving home, I said that I felt luckier than Tom. I know nothing is going to happen with my book. My book is going to sell 20 or 50 copies, and I accept that.”

They talked about art and the bottom line and youth today. They speculated on whether McHale had a contract for a seventh book. Someone said yes.

Publisher Rosemary Jones looked up impatiently.

“It is awful to have this be reduced to gossip,” she said.

A jocular health book publisher who took photos –later lost — of the publishing party said, “Let’s just remember the smiles.”

Later, Myra Gross recalled quiet times with McHale, funny stories he told while monopolizing the conversation. She didn’t mind. A single woman, a working mother, a writer, she knows something of what McHale faced — something about being alone and afraid, about art and rent. Here in these same suburbs she lives on as best she can.

“Maybe I’m more practical,” she says. “Maybe I learned to compromise along the way.”

thank you for posting this

Tom McHale is a nice novelist, my friend on EbonyFriends.com and I like the novelist, we all like to read the novels very much.

thank you for the article.

Tom was in a class of mine in writing at the University of Pennsylvania in the early ’60s. He came ready-made, brilliant; there was nothing for him to learn in any class of mine. He is one of the most original of American writers, his satire disguising deep, intuitive thought about the nature of this strange, cruel place. If you’ll look at the back of a first edition of Principato, you’ll see my testament to it. I was a reference for his Guggenheim, and he was once a guest at my farm in upstate New York, driving up in his much-loved Citroen. We lost touch, and I mourned when I heard of his heart-breaking death. As so many of us do, taught by our fathers, he confused commercial success with literary success and felt he had failed. He was an artist with greatness.

I remember working as a waiter with Tom(RIP) in Tamiment resort

in Pennsylvania ’68 or’69…Nice guy but aloof…He was like a Kennedy,the fair-haired Irish kid destined for success…Unfortunately,he inherited the Irish curse for booze and the Kennedys’ curse …As Oscar Wilde once said of Diane Arbus’ suicide:”a great career move”…In McHale’s case, a sad move…I once went to the main New York Public to look up Tom’s books and they were not there! It was

almost as if he was never published…Rest In Peace…FG

My parents had told me about Tom McHale when I was growing up around the time that he died. They had both worked with him at the Department of Public Welfare in Philadelphia, and my father had even shared an apartment with him at Broad and Allegheny.

I just started reading his books now that I’m nearing the end of my 30s and working as a caseworker here in Philly now. I started with “Farragan’s Retreat” and I’m halfway through “Principato” now. Both really bring out the feeling of being a somewhat lapsed Catholic, dealing with modern times here in the City of Brotherly Love.

Much like many other things my parents told me when I was a teenager, I should have started reading McHale much earlier, but better late than never, I guess.

I went to high school with Tom (Scranton Prep 1955-1959)and knew him pretty well. We used hitchhike home together, he to Avoca, I to Pittston. And we would often double date. Even though we went to different colleges and grad schools we kept in touch. When I married in 1966 Tom sent a congratulatory telegram from Paris. When he was in the area we would have dinner. I attended his wake and funeral but never knew he had taken his life till I read it in Time Magazine. I see his brother, Johnny, on occasion but we never speak of Tom’s death. I like to remember Tom as he was in high school.

Tom McHale taught creative writing at Monmouth College, now Monmouth University, in West Long Branch, NJ in the late ’60’s, after publishing Principato and then Farrigan’s Retreat. As a student, I found him bright, sensitive, supportive, engaging, and very different from the other “literature” professors. His preoccupation with his image, his potential, his early success, his literary “place,” and long term viability, emerged clearly both in class and outside of class.

One very memorable session turned into a class critique of a “Christmas Story” that Tom wrote on deadline for a woman’s magazine. The students gave it mixed reviews as it really was not powerful, poignant, or Pricipato-like. Tom showed his disappointment in both the story itself and the students’ comments on it. At that early stage in his career, one could see that he had 100% of his identity tied to his written work. Great story, great book, great reviews and he seemed to feel great about himself. Mediocre story, mediocre reviews and he felt devastated, possibly beyond the norm.

A few years later, I interviewed Tom for a local newspaper after he gave a talk to a small group of readers and writers in New Jersey. He faced transition again, personally and professionally, and his preoccupation with self-evaluation and comparison to others didn’t take more than one beer to reveal. Then, as now, I wondered what activity, what hobby, what job, what relationship Tom could have embraced so that the highs and lows of his writing career would not consume him. Surely, his intelligence, creativity, humor, sensitivity could have found another platform to provide more consistent, positive SELF-reviews.

Damn shame no one could help him see that potential and guide him to it.

Tom certainly gave his students many memorable lessons on the art of writing, but in the end, his most valuable lesson concerned mental health–the need for balance and back up plans. Peace, Tom. Yes, you were both a great guy and a great writer.

Tom taught a creative writing class in 1980 at Florida International University in Miami. I was one of his students. In 1982, I had a temporary job with the Florida State Employment Service and I met Tom as he was coming into the building. He was surprised to see me, since I’d gone to California for a Masters program after graduation, but it didn’t work out. I was equally surprised when he told me he was applying for a job teaching mentally challenged young adults. Even to me, a non-drinker, it was clear he’d been drinking. I felt bad for him because he seemed lost.

He was a charming, bright, funny man who couldn’t battle his demons. That is so sad.